Soviet Repressions Against the Estonian Political Elite in 1944–1953

During the first year of the Soviet occupation (1940-1941), a considerable part of the political and social Estonian elite was repressed – these individuals were imprisoned, deported, or executed. In the summer of 1941, the German occupation replaced the Soviet occupation. But it lasted only until the summer-autumn of 1944. As the German forces retreated, the Soviet Union re-occupied three Baltic states. When Soviet security agencies returned to Estonia in the autumn of 1944, they resumed carrying out repressions.

This article is previously published in a memorial collection “At the Will of Power. Selected articles”. it contains the most important and best part of his research. The book can be purchased online from the National Archives of Estonia, Apollo and Rahva Raamat.

In the report Fate of the Estonian Elite in 1940– 1941, I considered the fate of the Estonian political elite (Heads of State, members of governments and Parliament, justices and public servants of higher rank, leaders of local governments) during the first years of the Soviet occupation (1940–1941).

The goal of the present article is to present a statistical resume and to describe the fate of the rest of this group during the next period of the Soviet occupation, in 1944–1953, and to analyse to what extent their previous status as members of the Estonian elite affected the course of their lives.

Also in Estonian history, 1944–1953 denotes a period known in historiography as late Stalinism – from the end of military action in the Estonian territory to the death of Iosif Stalin. The records we have examined give a very clear indication of the end of the named period in terms of human destinies.

In 1953, the last of the victims considered here died at prison camps, and already in 1954 we encounter the first cases of commuted sentences. Of the whole of this group, only one person is known to have been repressed after 1953, this was Johannes Pärtma, Tuhalaane rural municipality mayor, who was arrested in 1955 and had simply been lucky to escape arrest earlier.

The article is based on comprehensive lists drawn up on the basis of archive records and Riigi Teataja (State Gazette). As concerns members of government, all governments from 1918–1940 will be considered, while in other categories I have limited the research to the last members in office, i.e. members of the Riigikogu (Estonian Parliament) who entered office in 1938 and the public servants and staff of local governments who were actually in office immediately before the start of the Soviet occupation on 17 June 1940.

Also investigation files compiled by the Soviet security agencies have been used to throw light upon the fate of the repressed.

Methodologically, I have concentrated on three documents: 1) regulation of arrest, 2) indictment, 3) verdict.

The regulation of arrest was, together with a restraining order ("chosen means of restraint"), presented by the investigator to a higher authority of the investigating body and also to the Chief Prosecutor’s Office for sanctioning. On the basis of an order of arrest, drawn up on the basis the regulation of arrest, the individual was arrested.

In practice, the arrest was mostly applied to individuals who had already been detained, although also free individuals could be arrested. As it became an established practice in the Stalinist security structures to arrest people to whom no indictment had been read, i.e. suspects, the "description of crimes" in the regulation of arrest must be considered as a suspicion.

Of course, the judicial term of "suspect", belonging to the judicial systems of the rule of law, is not quite appropriate in this context, because as rule, the arrest was a turning point in a person’s life, and the number of those who managed to escape the mechanism of the regime after their arrest was extremely small.

It is also important to keep in mind that the regulation of arrest, i.e. the contents of the suspicion, were kept from the arrestee, he was presented with the order of restraint, which only contained references to numbered sections of the Criminal Code of the Russian SFSR, which could not be comprehensible to a layman; this practice was contrary to the principle of criminal investigation of an individual’s right to be informed of the nature of suspicions against him.

The indictment can tentatively be divided in two parts (this is not an "official" division, but one used in this article for the purpose of clarity):

- "the plot/the story" or the description of crime, with reference to proof to be found in the file and;

- the indictment with the personal data of the accused and an extract of the respective section of the Criminal Code. The indictment was usually much shorter than "the plot", and contained only part of the circumstances enlisted in the above.

"The verdict" was the tribunal’s or court’s verdict convicting the individual or sentencing him to punishment through Special Board. The verdict3 of a judicial assembly consisted (officially) of two parts, the descriptive and the resolutive. The first part contained the formal indictment, the personal data of the accused, and the circumstances of the crime.

The resolutive part indicated the identity of the accused, the formal accusation against him in accordance with the respective section of the Criminal Code, and the sentence of punishment or acquittal. In addition, the second part was supposed to mention the possibility of appeal. The resolution of the Special Board was added to the file in the form of an extract of the minutes of meeting of the Special Board.

That too consisted of two parts – the first part containing information about the relevant file and the individual considered in the file, the second part listing the elements of the individual’s crime in free wording, without reference to any sections of the law, as well as the punishment imposed on him (the punishment was proposed to the Special Board in the indictment). The body responsible for the sentence could change the accusation and its qualifications, or acquit the accused, etc. The latter was an extremely rare occurrence.

The verdicts, as a rule, had the same content as the indictment. It should be kept in mind that at a Special Board, there was no real discussion of the case – and when considering the tradition of the rule of law, there was none at the courts or tribunals either.

Although the sentences were, as a rule, formalities, this does not exculpate the individuals who imposed the sentences from the responsibility of convicting and punishing citizens of an occupied state. For example, there can be no doubt about the accusation of the betrayal of motherland, meaning the USSR, being in conflict with the regulations of international law.

Members of governments

Of the former Heads of State, two of the eleven men were still alive in 1944: Konstantin Päts at a prison camp in Russia, and August Rei, who had fled to Sweden in 1940 and stayed there. All the other former Heads of State had been executed in 1941–1942 or perished at the Soviet prison camps.

Nor were there many men left of the last Government of the Republic by 1940. At the moment of the re-establishment of the Soviet occupation, two of the eleven members of the Government were still alive: the Minister of Education Paul Kogerman, who was at the NKVD prison camp (he was released in 1945, when his knowledge of oil shale chemistry was needed for building up the Estonian oil shale industry), and the Prime Minister and Acting President Jüri Uluots, who had been evacuated to Sweden in September 1944, already bedridden with severe illness, and died there on 9 January 1945.

All in all, there had been 116 men in the governments (including the provisional governments) of the Republic of Estonia during the 22 years of independence. 49 former ministers had been imprisoned during the first years of the Soviet occupation, in 1940–1941; 45 of them were either executed or died at prison camps.4 10 of the former ministers were arrested by the Soviet security structures after the war, and four of them survived their imprisonment.

The most prominent of them was Otto Tief, whose occupation as Minister of Labour and Social Welfare and Minister of Justice in earlier governments (1926–1927) was eclipsed by his seat of Deputy Prime Minister in the Intermediate Government (mostly known as Otto Tief’s Government) of 1944.

Otto Tief was arrested on 10 October 1944, taken to Moscow and convicted, with six others of similar fate, on a closed session of the Military Division of the Supreme Court of the USSR, presided by Vasiliy Ulrich, on 3 July 1945. Tief’s punishment was 10 years of corrective labour camp, followed by deprivation of rights for 5 years. Tief was released in 1956 and returned to Estonia in 1958, but that was not the end of his tribulations.

Bernhard-Aleksander Roostfelt, an agronomist, economist, social figure and politician, member of the Riiginõukogu (the Upper House of the Riigikogu, elected in 1938) and minister of several governments in 1921–1924, was arrested on 8 November 1944. The regulation of arrest suspected him of attempting to leave Estonia illegally.

He was detained on 1 November in an alleged gathering point, a house at 18 Viru Street, Tallinn, together with August Priima, the "go-between". On 28 February 1945, an indictment was drawn up, asserting that Roostfelt, living in the territory occupied by German troops in 1941–1944, and having contacts with Germans, had been engaged in criminal work directed against the Soviet power.

Roostfelt pleaded guilty of only part of the crimes, and as the witnesses Susi and Nemirovich-Danchenko were not present in Tallinn, the tribunal did not have enough proof. Yet Roostfelt was found to be a "socially dangerous element", and therefore the case was, in accordance with Section 208 of the Criminal Procedure Code, delegated to the Special Board of the NKVD of the USSR for revision. The proposed punishment was 10 years of corrective labour camp.

This is, by the way, an interesting and rare sentence, where the system, half-unconsciously, reveals its nature – the case is too weak to hold water even in a Soviet court or tribunal, and yet the elimination of a specific person is considered necessary. In such cases, the Special Board was used as a quasi-court in the Soviet Union.

On 26 May 1945, the Special Board sentenced Roostfelt to 8 years for "treason to motherland" in accordance with Article 58-1"a". Roostfelt died while serving his sentence in the prison camp of the city of Karaganda on 26 January 1948.9 Also, he was the only member of the Riiginõukogu who was repressed after the war.

Aleksander Veiderma, Minister of Education in two governments in 1922–1924, was arrested on 10 November 1944. In the regulation of arrest he was characterised as an individual hostile to the Soviet regime, who had in 1941–1944 defected to the side of the enemy and in January 1944 given a speech in the Tallinn Town Hall to the "Tallinn Defence Battalion" as its former "Company Commander", inciting men to fight against the Red Army for the independent Estonia.

According to the indictment presented on 21 February 1945, Veiderma, while living on an occupied territory (1941–1944), had committed treason to motherland, being a member of Omakaitse for six months and urging the men of the former Defence Battalion to take arms against the Red Army. The "plot" part of the indictment also mentions the post of the Minister of Education in a "bourgeois government".

On 15 March 1945, the Military Tribunal of the NKVD Troops in the ESSR sentenced Veiderma to 10 years of corrective labour and 5 years of deprivation of rights and confiscation of property in accordance with Article 58-1"a" of the Criminal Code. The minister’s office held by him in the past was mentioned also in the minutes of the court session. Veiderma was released from prison camp after having served his sentence.

Nikolai Talts, Minister of Agriculture in 1933– 1938, was detained on 16 November 1944; the detaining order mentioned the post of minister in a "bourgeois government" and suspected contacts with the National Committee of the Republic of Estonia (the EVR). In the regulation of arrest drawn up on 6 January 1945, the Senior Lieutenant of State Security Filimonov found Talts to be a former Minister of Agriculture of a "bourgeois government" and have close connections to the "underground national committee". Of his activities connected to the EVR, Talts had spoken already on his first interrogation on 15 November 1944.

The indictment was presented on 11 August 1945, and consisted of professional activities during the German occupation (Talts had been a legal consultant of the Forestry Administration of the Estonian Self-Administration) and the fact that in September 1944, Talts had advised his acquaintances to flee to Sweden.

On 25 February 1946, Special Board sentenced Talts to 5 years of corrective labour camp as a "socially dangerous element", with confiscation of property. The sentence was imposed in accordance with Section 7 of the Criminal Code, which states: "To individuals who have committed acts hazardous to the society or who are a hazard to society because of their contacts with criminal sphere or their own previous activities, means of social defence of respectively judicial-corrective, medical, or medico-pedagogical nature shall be administered. Talts was released in 1949.

Aleksander Tulp, who had been Minister of Labour and Social Welfare very briefly (and in fact only pro forma) in 1918, was arrested on 12 December 1944. According to the regulation of arrest, Tulp had been an active Menshevik in the past and was hostile to the Soviet power; as a chairman of the Socialist party he had contacted the "Anti-Soviet nationalist government" for the co-ordination of political issues, as well as participated repeatedly in the underground meetings of the above government, one of which, that also Tulp took part in, took place in Tallinn in October 1944.

The indictment was dated 30 May 1945. It accused Tulp of bourgeois nationalism and hostility towards Soviet power, as well as of being an active counterrevolutionary and member of the Socialist party. Living in Estonia under the German occupation, he had had close relations with the EVR and members of the underground government, and been their supporter and sympathiser.

The case was delegated to a NKVD Special Board, with the proposed sentence of 10 years of corrective labour with confiscation of property. The Special Board sentenced Tulp as "a henchman of the traitors of motherland" to five years on 8 September 1945.20 Aleksander Tulp was released in 1950.

Jaak Reichmann, a member of the judiciary circles of the Republic of Estonia, who twice had been Minister of Justice and a long-time President of the Court Chamber, was interrogated for the first time on 2 December 1944, but released on that occasion. He was called to Pagari Street again on 23 January 1945, and that proved a point of no return. On that day, Reichmann was interrogated and thereafter arrested.

Senior Lieutenant of State Security Ryzhkov, the operative officer of the NKGB of the ESSR, who drew up the regulation of arrest on 24 January 1945, found that Reichmann had stayed in the territory occupied by Germans and entered office in the judicial system of the occupying powers and, being a judge of the Tallinn Circuit Court in summer 1942, he was in August of the same year appointed President of the Court Chamber by Commissar General Litzmann at the proposal of Hjalmar Mäe, Head of the Estonian Self-Administration, and remained in office until September 1944. It was also mentioned that Reichmann had been "Minister of Justice of a bourgeois government" in 1921–1922. Such activities were classified under Article 58-1"a" of the Criminal Code.

The only witness, heard on 22 January, was Roman Koemets, a former colleague of Reichmann. Special attention was given to the statement where Koemets characterised Reichmann as a supporter of the "Agrarian Party" and described his professional activities during the German occupation.22 Reichmann himself was for the third and last time interrogated on 5 March.

On 11 March, Reichmann, who was 71 years old and in poor health, was transferred to the prison hospital. His wife Anna Reichmann had been right, when writing in her letter of appeal to Johannes Vares, Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the ESSR, that her husband is severely ill and in need of constant care and would probably die in prison atmosphere. Reichmann died on 1 May 1945. The medical spravka (certificate) stated that Reichmann had been in need of urgent surgery, and that the surgeon had refused to perform it. The case was closed on 17 May 1945.

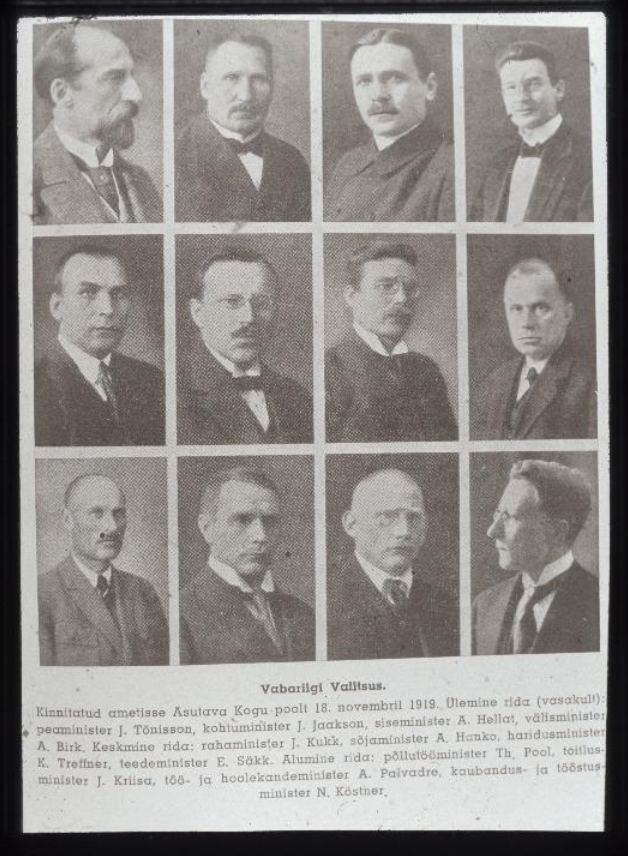

August Hanko was Minister of War in 1919–1920, in Jaan Tõnisson’s government. He was arrested on 16 April 1945, and the regulation of arrest mentioned the office of the Minister of War, who had "led and organised the struggle of the Estonian bourgeoisie against the Red Army"; also, Hanko had allegedly been of anti-Soviet frame of mind and published anti-Soviet articles in the press during the German occupation (the proof included the article "Budding Ideas for Freeing us from the Russian State" from 15 March 1943).

His criminal activities were found to be corroborated by the statements of Hanko himself and the witness August Tõllassepp, "and other materials". It is true that on his first interrogation (before the formal arrest) when speaking of his life, Hanko had also mentioned the office of the Minister of War (the respective paragraph of the minutes has been underlined in red). Tõllassepp had been interrogated as a witness two days earlier, on 14 April. He had known Hanko since childhood and, as to his political activities, knew that Hanko had been Minister of War in 1919–1920.

On 17 July 1945 the indictment was presented, charging Hanko only with publishing a slanderous anti-Soviet article, which was considered to be a crime according to sub-section 2, Article 58-10 of the Criminal Code. The charges under Article 58-1"a" had been reclassified on the eleventh hour. The indictment did not mention his minister’s office.

On 16 August, Hanko was tried by the Military Tribunal of the NKVD Troops in the ESSR, presided by 1st Lieutenant of Military Judicial Service (hereinafter MJS) Shamanayev (Captain Günsberg and Lieutenant Pankov were members of the tribunal) and sentenced to 7 years in corrective labour camp and deprivation of rights for 3 years, with confiscation of personal property, in accordance with sub-section 2 of Article 58-10 of the Criminal Code. Hanko was released from camp on 16 April 1952 and died, according to his son, in the settlement of Arlyuk in Kemerovo Oblast on 25 May 1952.

Karl-Ferdinand Kornel, Minister of Trade and Industry in two governments in 1926–1927, was arrested on 28 November 1945. According to the regulation of arrest, Kornel was "a social and political figure", member of the Constituent Assembly and the 2nd and the 3rd Riigikogu (1923–1929), Minister in two Governments. In 1930–1940, he had been Director of the Estonian Telegraph Agency, and during the German occupation a referent to the Director of Economy.

The indictment was presented to him on 11 March 1946, and the charges were that Kornel was hostile to the Soviet power and had been a correspondent to the newspapers Eesti Sõna(Estonian Word) and Meie Hääl(Our Voice) and slandered the Soviet power in his articles.

In addition, he had been Commandant of the town of Haapsalu in 1944 and "taken action for founding the city police". "The plot" mentions also Kornel’s earlier office as Minister.31 On 10 April 1946, the Military Tribunal of the NKVD Troops in the ESSR sentenced Kornel to 10 years of corrective labour without confiscation of property in accordance with Article 58-1"a".32 Karl Kornel died in prison camp on 31 July 1953.

Gustav Viard, a military man, who had been a Minister pro forma for a few days in 1920, was arrested on 13 November 1950. It was found in the regulation of arrest that Viard had, during the "bourgeois government", served in the "bourgeois army" of Estonia "in the rank of Colonel", and been one of the five persons who gave evidence to the SD against Eerik Kaunismaa, a party candidate of the Tallinn Metal Plant in September 1941, and that on the basis of that evidence, Kaunismaa had been sentenced to death and executed. The document did not mention his Minister’s post.

On 16 March 1951, an indictment charging Viard with giving evidence to the SD and retaining illegal literature was presented. On 30 March the Military Tribunal of the NKVD Troops in the ESSR (presided by MJS Colonel Dytyuk, members Belyakov and Smirnov) convicted Viard in accordance with Article 58-1"a" of the Criminal Code and punished him with 25 years of corrective labour, deprivation of rights for 5 years and confiscation of property.

Viktor Pihlak, construction engineer and industrialist, who had been pro forma Minister of Trade and Industry for a couple of days in 1920 (in the same government with Gustav Viard), was arrested on 23 February 1951, when employed as a foreman in the Kopli Machinery Plant in Tallinn.

Captain Orlov, who had drawn up the regulation of arrest, found that Pihlak had, in 1919, voluntarily served in the "white Estonian army" and participated in the "so-called War of Independence", and from June 1919 to November 1920 been assistant to and employed as an acting Minister of Trade and Industry "in a reactionary bourgeois government", and had in 1947 had contact with individuals wanted by Soviet security agencies and given them material assistance. Pihlak’s criminal activities were corroborated by the evidence of the witness Arno Pihlak, records of the State Archives of the ESSR, and "other documents".

In 1950, an archival notice on Pihlak’s activities was drawn up in the Central State Archives of the October Revolution and Erection of Socialism of the ESSR (before and afterwards, Estonian State Archives). The notice contained his entire curriculum vitae, including the post of minister.

The indictment was presented on 31 October 1951; in accordance with Articles 58-4 and 58-10, Pihlak was accused of being a supporter of the bourgeois regime, who had voluntarily joined the army and participated in the War of Independence, been administrator of the Ministry of Trade and Industry in 1919–1920, and retained anti-Soviet literature. The minister’s post was not mentioned in the document.

On 17 November 1951, the Criminal Division of the Supreme Court of the ESSR (presided by Afanasyev, members Königsberg and Urva) convicted Pihlak (the main charges being participation in the War of Independence and retaining of illegal literature) and sentenced him to 10 years in camp and 5 years of deprivation of rights and confiscation of property. The former industrialist Pihlak was a comparatively wealthy man even in 1951, the register of his property covers 10 pages in the file and the property was estimated to 5375 roubles all in all.

In 1955, the Presidium of the Supreme Court of the ESSR reviewed the case and commuted the sentence to 5 years. By a regulation of the Supreme Court of the USSR the sentence was declared null and void due to absence of necessary elements of a criminal offence, and Pihlak was fully rehabilitated.

Members of the 6th Riigikogu (1938–1940)

According to the Constitution of 1938, the Estonian Parliament, the Riigikogu, was a bicameral representative assembly consisting of the Riigivolikogu (the Lower House) that had 80 elected members, and the Riiginõukogu (the Upper House), which had 40 members. The latter had ex officio members, members nominated by the President, and members elected by local governments.

In 1940–1941, 19 members of the Riiginõukogu were arrested, and all of them were either executed or perished in prison camps. At least 12 former members of the Riiginõukogu managed to reach exile. According to the data available so far, 8 members of the Riiginõukogu escaped repression.

The only member of the Riiginõukogu known to have been repressed after the war was Bernhard Aleksander Roostfelt, his fate was already described in the sub-chapter "Members of Government".

Of the 80 members of the Riigivolikogu, exactly a half were imprisoned in 1940–1941. Of those, only one, who was released in 1948, survived imprisonment. 26 members of the Riigivolikogu were sentenced to death and shot in 1941–1942, five died already during preliminary investigation and 8 in the prison camps of Russia. Two members of the Riigivolikogu were killed as forest brothers in the summer of 1941 and two were executed during the German occupation. At least 15 members of the last Riigivolikogu managed to reach exile. According to the available data, 14 members of the Riigivolikogu escaped the repressions.

Six members of the Riigivolikogu are known to have been imprisoned by the security agencies of the Soviet Union after the end of military action in Estonia in 1944. Three of them (Juhan Kaarlimäe, Karl-Eduard Pajos, Värdi Velner) were also county governors, and shall therefore be considered in the respective sub-chapter. Oskar Gustavson was arrested because of his contacts with Otto Tief’s government and the National Committee of the Republic of Estonia. There is no verified data about his fate, but allegedly he died in 1945 in Tallinn, when trying to escape from a NKVD interrogation.

Eduard Peedosk, member of the 6th Riigikogu and active figure of local government, was arrested on 17 November 1944. The Võru County Department of the NKGB, who had drawn up the regulation of arrest, found Peedosk to be hostile towards the Soviet power; also, he had voluntarily joined the Omakaitse in 1941 and at the same time been appointed to Räpina rural municipality mayor, and eagerly fulfilled all orders of the German powers he received in this capacity.

On 13 November a local inhabitant Antonina Ivanova was interrogated as witness, and said that as rural municipality mayor, Peedosk had fulfilled all orders of the German authorities, had a bad attitude towards poor farmers and protected the interests of rich landowners. According to Ivanova, Peedosk had been especially cruel to Russian inhabitants evacuated from the Soviet Union. Once, when Ivanova asked for some leather from the shop to make boots for her daughter, Peedosk had allegedly answered: "We have nothing for you Russians. Only for our own people."

On 12 November, witness Peeter Mets said that Peedosk had joined the Omakaitse voluntarily and was one of its organising forces. He had allegedly been deputy to the commander of Räpina Omakaitse, who did not participate in operations himself, but issued orders to "establish order in the rural municipality" and to purge the rural municipality’s territory from the Soviet people. In addition to those records, there was August Kõiv’s evidence from 7 November.

On 28 January 1945, Peedosk was presented an indictment consisting of hostility towards the Soviet power, active participation in the Omakaitse and employment as rural municipality mayor during the German occupation, as well as fulfilment of orders received from occupying powers, collecting taxes and imposing fees on tax evaders.

On 31 March 1945, the Military Tribunal of the NKVD Troops in the ESSR sentenced Peedosk to the typical 10 years of corrective labour and deprivation of rights for 5 years in accordance with Article 58-1"a" of the Criminal Code. Property was not confiscated due to absence of property. Eduard Peedosk was released from imprisonment on 30 October 1954.

Another repressed member of the Riigivolikogu, a well-known local government activist Mihkel Reiman was arrested on 28 December 1944. The Järva County Department of the NKVD, who had drawn up the regulation of arrest, pointed out that in August 1941, Reiman had been appointed mayor of Väätsa rural municipality and remained on that post "until Estonia had been liberated by the Red Army". As rural municipality mayor, he had appropriated land from the farmers who had received it from the Soviet power in 1940, and organised the obligatory collection of agricultural products.

The indictment was presented on 28 August 1945, and included charges for living in an occupied territory, treason to motherland, employment as Väätsa rural municipality mayor (incl. "helping the occupying powers to execute their policies"), hostility towards Soviet power, "pro-Fascist" propaganda and membership in the Omakaitse in 1944.

On 19 September 1945, the Military Tribunal of the Tallinn Garrison sentenced him to 10 years of corrective labour and 5 years of deprivation of rights, plus confiscation of property, in accordance with Article 58-1"a" of the Criminal Code. Reiman’s buildings were appropriated, and his agricultural equipment, as well as fodder and cattle consisting of 3 horses, cows, swine and sheep with lambs, and 2 heifers, were confiscated from him.

Supreme Court of the Republic of Estonia

The Supreme Court was the court of highest instance of the Republic of Estonia, and in 1940 it had consisted of 16 justices. The long-time Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Kaarel Parts died of natural causes on 5 December 1940. Six justices of the Supreme Court were arrested in 1940–1941, all died in prison camps.

In addition, one justice of the Supreme Court perished during an escape over the Baltic Sea in the autumn of 1944, and another one besides Kaarel Parts died in 1940. Five of the justices of the Supreme Court who had been in office in 1940 escaped repressions. In 1944–1945, two justices of the Supreme Court Karl Luud and Roman Koemets were arrested by the Soviet security agencies.

Karl Luud was arrested on 30 October 1944. According to the regulation of arrest, he was accused of staying in the territory occupied by Germans, entering the service of the "German Directorate of Justice" [in fact, the Directorate of Courts of the Estonian Self-Administration – I . P.] in February 1942, of employment as member of the Kuressaare Circuit Court and later as member of the Court Chamber, "thus actively helping the German occupying powers".

The indictment presented on 23 December 1944 listed the charges of staying in an occupied territory, treason to motherland, and employment in the Directorate of Courts, the Circuit Court and the Court Chamber. On 17 January 1945, the Military Tribunal of the NKVD Troops in the ESSR convicted Karl Luud with the above charges in accordance with Article 58-1"a" of the Criminal Code and sentenced him to 10 years of corrective labour with confiscation of personal property.

Roman Koemets, the other repressed Justice of the Supreme Court, was arrested on 26 January 1945 and accused of staying in the occupied territory and entering the service of the judicial organs of the occupying powers (more specifically, employment at a Circuit Court and, from summer 1942, in the Court Chamber, was named).

In June 1945, the Koemets case was tied up with the cases of Eduard Mailend, Oskar Ordlik and August Kroon, for the reason that all four had worked in the judicial system of Estonia during the German occupation. All four had been arrested in January-February 1945.

On 30 June 1945 an indictment was presented; it did not mention work in the judicial system during the independence period in any of the cases. On 8 September 1945 the Special Board of the USSR NKVD punished all four of them for treason to motherland in accordance with Article 58-1"a" of the Criminal Code, but the sentences were different. Mailend and Kroon were sentenced to 7 years of corrective labour with confiscation of property, while Ordlik and Koemets were sentenced to 7 years of forced settlement in Tyumen Oblast, also with confiscation of personal property.

Public servants

In 1940, there were 133 senior public servants in Estonia according to the registers.56 Thirty-nine of those had been repressed already in 1940–1941, and the major part of the rest left Estonia in 1944. After the war, the Soviet power imposed repression on a few of them, 5 cases are known.

August Leppik, Director of the Land Cadastre and Readjustment Department of the Ministry of Agriculture, was arrested on 28 November 1944. According to the regulation of arrest, Leppik had entered the service of the occupying powers at the beginning of the German occupation, working as deputy to the director of the Land Readjustment Department [i.e. on the same post as before, which was quite common among public servants – I. P.] and been involved in returning to kulaks the land appropriated from them by the Soviet power in 1940. Besides, Leppik was suspected of contacts with Kaarel Liidak, the leading figure of the National Committee of the Republic of Estonia.

Leppik was interrogated for the first time on 23 November, when he spoke of his positions as public servant without concealing anything. To the question: "Why were you appointed to this important position?" Leppik answered: "Because I had been Director of the Land Readjustment Department of the Ministry of Agriculture until July 1940".

On 17 May 1945 an indictment was presented, containing the same charges — his position as Director of the Land Readjustment Department, "serving the German powers" and returning the land to former owners. In addition, Leppik was accused of disclosing his anti-Soviet ideas in a publication "On Independent, Sovereign Estonia".

On 31 May 1945, the Military Tribunal of the NKVD Troops in the ESSR, presided by MJS 1st Lieutenant Shamanayev and with Prokofyev and Suslov as members, sentenced him to 10 years of corrective labour and 5 years of deprivation of rights, and confiscation of property, in accordance with Article 58-3 of the Criminal Code. August Leppik died in prison camp on 16 May 1947.

Herman Perna, Head Inspector of the Ministry of Transport, was arrested on 26 December 1944 as a "bourgeois nationalist and a furious antagonist of the Soviet regime", who had remained on the territory occupied by Germans in 1941 and voluntarily co-operated with the occupying powers, and been appointed senior auditor of the Estonian Railways by those.

Seven other men were tried together with Perna, all had been employed on senior positions in the railway authorities during the German occupation. Their indictment was presented to them on 5 March 1945. On 24 March 1945 the Military Tribunal of the Estonian Railway presided by MJS Major Sarin sentenced the men to different terms of imprisonment. Herman Perna was sentenced to a corrective labour camp for 10 years, with deprivation of rights for 4 years and confiscation of property.

Aleksander Roosileht, Head of the Dairy Export Inspection Station of the Farming Department of the Ministry of Agriculture, and Chairman of the Inspection Committee, was arrested on 4 July 1945. According to the regulation of arrest drawn up in the Tartu County Department of the NKGB, Roosileht had joined Omakaitse voluntarily in 1941; had owned a rifle and a pistol as a member of Omakaitse, and stood armed guard to the Germans’ objects of military importance.64 The indictment presented on 15 March 1946 also points out service in the Omakaitse, and that Roosileht had exploited Russian prisoners-of-war in his household.

The case was handed over to a Special Board for issuing a verdict, and the proposed punishment was 8 years of corrective labour.65 Proceeding from Articles 58-1"a" and 58-11 of the Criminal Code, the Special Board sentenced him to a bit milder punishment, 6 years of corrective labour camp for "participation in a military-fascist organisation". Roosileht served his sentence in Bogoslovlag and was released by the Enactment of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR from 19 May 1948.

Eduard Jõerüüt was head of the financial department of the Railways Administration of the Ministry of Communications, and member of the Tariff Council. He was arrested on 14 September 1945 and the regulation of arrest mentioned his "employment in senior positions of the bourgeois government" as a reason; according to that document, Jõerüüt had been assistant to the Director of Estonian railways up to 1940.

Jõerüüt was also found to be hostile towards Soviet power, and the fact that although he had a possibility to leave Estonia in August 1941, he had not done so, but had instead entered the service of occupying powers as Deputy Director of Railways, was mentioned too. Eduard Jõerüüt had indeed been appointed Deputy Director of Estonian Railways on 29 August 1941 by the German military authorities.

The indictment was presented on 26 November 1945. The indictment emphasised the refusal to be evacuated into the Soviet rear and active co-operation with the German occupying powers.

As railway official, he was tried by the Military Tribunal of the Estonian Railway. Their verdict from 7 December 1945 convicted Jõerüüt of co-operation with the German occupying powers in accordance with Articles 58-2 and 58-3 of the Criminal Code, and sentenced him to 7 years of corrective labour with 4 years of deprivation of rights and confiscation of property.

Friedrich Vendach, the former assistant director of the construction department of the Ministry of Communications, was arrested on 29 May 1951. The regulation of arrest was drawn up by Lieutenant Shamshurin, operative official of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, on 24 may 1951; it claimed that Vendach had at home "a considerable amount of acute anti-Soviet and counter-revolutionary literature from the bourgeois period and the period of [German] occupation, containing slander addressed against the USSR and propaganda of Hitlerism". In addition, Vendach had participated in the War of Independence as non-commissioned officer, been engaged in the movement of the War of Independence Veterans’ League, been a supporting member of the Defence League and City Counsellor of Nõmme.

The indictment presented on 21 July listed, on the whole, the same charges, although it mentioned service "in the police and other public institutions of the Republic of Estonia". On 7 August, the Supreme Court of the ESSR convicted Vendach in accordance with Articles 58-4 and 58-10 of the Criminal Code and sentenced him to 25 years of corrective labour with deprivation of rights for 5 years and confiscation of property.

Thus, none of the documents contained an explicit accusation of employment in a senior position as public servant. In 1954 the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the ESSR commuted the sentence to 10 years by way of clemency. Vendach was released in 1955.

Officials of local government

In the Republic of Estonia, the system of local government had two levels, and in 1940, there were 11 counties and 248 rural municipalities. The last elections to rural municipality councils had been held in October 1939, and the last rural municipality governments had assumed office at the beginning of 1940.

The Rural Municipality Act, which had been drafted during and in the spirit of the period of authoritarian regime (1934–1940), gave a great extent of power to the rural municipality mayor, and as a rule, rural municipality mayors were influential men, local opinion leaders, who had been in charge of their rural municipalities for years.

Many of them had been in office during the entire period of independence. As the grip of the Soviet power was weaker in the country, the rural municipality mayors were a direct hazard to the occupying powers. Many of those men had also had influential positions in the local organisations of the Defence League and the Fatherland’s League, which gave the repressive structures of the Soviet Union a good pretext for imprisoning them.

County Governors

Of the county governors in office at the beginning of the Soviet occupation, only two managed to escape. Viljandi County Governor Mihkel Hansen and Harju County Governor Paul Männik left Estonia in 1944. Mihkel Hansen died in Toronto in 2004. Five county governors were arrested by the Soviet security agencies in 1941, two of them were executed, and the rest died in prison.

The remaining four (Juhan Kaarlimäe, Karl-Eduard Pajos, Värdi Velner and Mihkel Tang) were arrested in 1944–1945. The first three had been County Governors also during the German occupation, and Tang had been assistant governor of Viru County during that period.

Mihkel Tang, the last Governor of Petseri County during independence, in 1937–1940, was arrested on 28 October 1944. The regulation of arrest, registered on the following day, stated that Tang had a hostile attitude towards the Bolshevist party and the Soviet power, had in 1918 actively participated in battles against the Red Army as Adjutant of the 9th Regiment, and received a decoration from the "bourgeois government".

From 1921, he held various senior offices in the police structures (including the office of prefect), and was nominated to County Governor in 1937. In addition, Tang had been an active member of the Defence League and the Omakaitse. In 1941 he moved to Rakvere, where he was employed as Head of Department of Education and Social Insurance of the County Government. He was hiding in Tallinn in autumn 1944, and was apprehended there.

On the first interrogation, he was asked to tell the story of his life. Tang also mentioned his nomination to County Governor – this part of his story has been highlighted by underlining in the minutes.

The indictment, presented to him on 16 July 1945, stated that Tang, being hostile to Soviet power, stayed on in the territory occupied by the Germans and presented himself at the Tartu Kommandantur of the German Army on the first days of the German occupation, stating his wish to become Petseri County Governor.

In this office, he fulfilled all the orders and instructions of the Germans. In October 1941 he was transferred to Rakvere by Germans to become head of the Viru County Education Department, in which capacity he steered the schools "proceeding from the interests of the German conquerors", also informing the occupying powers of anti-Fascist manifestations among teachers, refused jobs to anti-Fascist teachers, or fired them.

On 27 August 1945 the Military Tribunal of the NKVD Troops in the ESSR, presided by MJS 1st Lieutenant Shamanayev (and with Lieutenants Grishanov and Solovyev as members) convicted Mihkel Tang in accordance with Article 58-3 of the Criminal Code and sentenced him to 10 years of corrective labour with deprivation of rights for 5 years and confiscation of personal property. Mihkel Tang died in a prison hospital in Leningrad Oblast on 8 July 1946.

The former Governor of Valga County Värdi Velner was employed as teacher at Restu School in autumn 1944, and arrested on 25 December 1944, suspected of having worked as "Mayor of Valga" during the German occupation and publishing an article slandering the Soviet power in a newspaper.

In addition, Velner was suspected of membership in the Fatherland’s League, the Defence League and the Omakaitse, and having been hiding in the forests and leading an anti-Soviet movement as a leader of a group of the forest brothers in 1941.

The indictment was presented on 21 March 1945, and stated that Velner was an individual of antiSoviet disposition and, during the German occupation, had been a voluntary County Governor, eagerly fulfilling all the orders of the occupying powers, and written an anti-Soviet article for a newspaper. His activities during the independence were not included in the indictment.

A month later, the Military Tribunal of the NKVD Troops in the ESSR, presided by MJS 1st Lieutenant Amirbekov (with Vaher and Sergeant Kasimov as members) sentenced Velner to 15 years of corrective labour camp with deprivation of rights for 5 years and confiscation of all personal property in accordance with Article 58-1"a" of the Criminal Code and Enactment of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR from 19 April 1943.83 Velner was released from imprisonment in 1955 and came back home. He died in 1992, having witnessed the restoration of Estonia’s independence.

Karl-Eduard Pajos, the former governor of Viru County, was arrested on 21 February 1945 as an "assistant of the German occupying powers". The respective regulation, where county governorship both during independence and the German occupation, as well as membership in the Defence League were mentioned, had been drawn up on the same day by Usginov, NKGB operative officer of the Viru County.

The indictment was presented on 24 May 1945 and, after additional investigation, again on 20 July 1946. He was accused of entering the service of the occupying powers during the first days of the occupation, and being appointed second deputy of Viru County Governor. In this office, Pajos fulfilled all the orders of the occupying powers "aimed at supplying the German Army with provisions". In addition, he had been member of the Omakaitse in 1944. Four inhabitants of Rakvere have been listed as witnesses.

On his interrogation Pajos said that he had been appointed deputy governor at the time of the German occupation because he had been employed thus earlier and had the necessary work experience. He was in charge of the departments of social welfare, roads, economy, and agriculture, and while responsible for those departments, he had to fulfil orders and instructions received from higher institutions and direct superiors. Pajos explained that the District Commissar of German civilian administration in Estonia had his own agricultural department, which arranged for the supplies for the German army.

On 9 October 1946 the Supreme Court of the ESSR, on a field session in Rakvere (Pajos was detained in Rakvere Prison, or Prison no. 5 of the NKVD of the ESSR), presided by Heinar Grabe (with Karjus and Lavrov as the people’s assessors) sentenced Pajos to 9 years with deprivation of election rights for 5 years and confiscation of all personal property in accordance with Articles 58-3 and 58-2 of the Criminal Code. Pajos died in 1953 at the Nyrob prison camp in Molotov (Perm) Oblast. The sentence was declared null and void in 1989.

Järva County Governor Juhan Kaarlimäe was the fourth former governor arrested in Estonia after the end of military action (on 9 December 1944). But in his case, quite different circumstances proved fatal: he had been a member of Otto Tief’s Government and was therefore taken to Moscow soon after his arrest. He was tried also in Moscow, with other members of Tief’s Government.

Rural Municipality Mayors

According to the data available so far, 38 rural municipality mayors were arrested by the Soviet power in 1940–1941. Thirty-four of them were killed in 1941–1942: 15 were shot, 7 died in prison camps after having been sentenced, 12 died under preliminary investigation. Four men succeeded in surviving the imprisonment and returning home many years later. In addition to those 38, two rural municipality mayors fell a victim to the Soviet destruction battalions in summer 1941.

In 1944–1955, 73 more rural municipality mayors are known to have been imprisoned by the security structures of the USSR. This great number is caused by the fact that the rural municipality mayors usually were leaders of the local Omakaitse formations, and members of the Omakaitse were pursued with special care by the repressive structures; also, the rural municipality members were, in official capacity, bound to participate in organising the collection of agricultural product rates, which made it easy to accuse them of collaboration with the German occupying powers.

In addition, it is known that 93 of those who had been assistant rural municipality mayors before the Soviet occupation were repressed in 1944–1955, as well as 32 rural municipality clerks. For assistant rural municipality mayors, the fact that many of them had served as rural municipality mayors during the German occupation, as the former rural municipality mayors were no longer there, proved fatal in many cases.

The Soviet power showed more clemency towards rural municipality clerks, who were in general not accused of collaboration with the occupying powers, because even in local governments, the principle of leadership was valid during the German occupation, and thus the rural municipality mayors had comparatively more executive power than earlier, which meant less responsibility for other officials, including rural municipality clerks.

On the other hand, I dare say that the Soviet power was unable to detect any danger in rural municipality clerks, as from the viewpoint of the USSR they were minor officials and not influential local opinion leaders, as had been the actual case in Estonia before the war.

Below, I will present some representative cases of rural municipality mayors.

Otto Tint, mayor of Sõmerpalu rural municipality in Võru County, was arrested on 11 September 1944 (at the time when the regions north of Emajõgi and west of Lake Võrtsjärv were still controlled by the German troops) and his fate proved different from that of many other rural municipality mayors. Guards’ Captain Mihalyev, deputy head of the 2nd division of the 1st Shock Army Smersh Department, who drew up the regulation of arrest, found that Tint was hostile towards the Soviet regime and had therefore started active struggle against it, joining a "gang" founded in Sõmerpalu rural municipality on 17 June 1941. This was followed by a list of acts of diversion committed by the forest brothers.

On 8 July, the forest brothers of the rural municipality were united into a local Omakaitse organisation, of which Tint assumed leadership. On 9 July this Omakaitse unit, under Tint’s command, had arrested "chairman of the rural municipality executive committee Herman Vilson, the secretary August Heim, deputy chairman of the executive committee Johannes Horula and Otto Venter, keeper of the [collective] shop". The arrestees were taken to Võru, where they were shot.89 On 10 July 1941, Tint resumed his office as Sõmerpalu rural municipality mayor and began restoration of the bourgeois regime.

As sources for the facts found, the document names "Tint’s own statements" from 9 September 1944, and a history of the Sõmerpalu Omakaitse, written by Tint in 1942. The latter was one of the several articles used for compiling an overview of the activities of the Estonian Omakaitse in 1942–1943.91 Tint had first been interrogated on 9 September, and in his curriculum vitae he also mentioned that in 1934–1939 he had been assistant rural municipality mayor of Sõmerpalu, and thereafter rural municipality mayor until February 1941.

The indictment, presented on 25 October 1944, listed the following charges: activity as a forest brother, membership in the Omakaitse, and office of rural municipality mayor in 1941–1944. No witnesses were mentioned, but there was mention of evidence and Tint’s personal records, which meant reports of the Defence League and Omakaitse activities written by Tint himself and others.

On 3 November 1944, the Military Tribunal of the 1st Shock Army (presided by MJS Colonel Kishchenko, with members Guard MJS Major Petrov and Lieutenant Deych), sentenced Otto Tint to "death by shooting" in accordance with Article 58-1"a" of the Criminal Code. The judgment was final, but had to be approved.

The respective approval is to be found at the beginning of Otto Tint’s investigation file: a letter bearing the signature of the Colonel General of the Military Judicial Service Vasiliy Ulrich, President of the of Military Division of the Supreme Court of the USSR, announcing that the verdict has been approved "by all instances" and that Ulrich has, on 5 February, issued an order that the judgment be carried out immediately. By the same document, Ulrich was requesting for a NKGB order to find and repress the adult members of Tint’s family. Otto Tint was shot on 12 February 1945.

The fate of Johannes Võmma, rural municipality mayor of Raikküla in Harju County, was similar to that of Otto Tint. He was arrested by Smersh on 13 October 1944, and Major Khamidulin of the 3rd division of the Smersh Department of the 13th Air Force Army, who had drawn up the regulation of arrest, found that Võmma was hostile towards the Soviet power and, having stayed on the occupied territory, organised the Omakaitse at the Germans’ orders in Raikküla rural municipality and acted as its chief.

In addition, he had joined the Defence League in 1927 and been commander of the Rapla territorial regiment of the Defence League in 1937–1939.95 His activities as rural municipality official were not mentioned in the regulation of arrest, but they were known to Smersh, as Võmma had talked about that in his life story during his interrogation on 11 October.

The indictment, presented on 26 December, concentrated on Võmma’s participation in the Omakaitse, emphasising his leading position, eagerness in battles against the Soviet partisans and parachutists, and in betraying the Soviet activists to the German powers. The "plot" part also mentioned Võmma’s service as officer in the Estonian Army in 1919–1923, and his active participation in the Defence League.

On 3 January 1945, the Military Tribunal of the Leningrad Front (Presided by mjs Major Petrov, members MJS Major Vinogradov and MJS 1st Lieutenant Shilov) sentenced Võmma to "death by shooting" in accordance with Article 58-1"a" of the Criminal Code. The judgment was "approved by all instances" and carried out on 7 March 1945.

August Altin, rural municipality mayor of Taheva in Valga County, was arrested on 28 November 1944. The regulation of arrest, drawn up by the Valga County department of the NKVD, listed the charges as office of rural municipality mayor in Taheva during the German occupation, membership in the Omakaitse, and participation in raids for evaders of mobilisation.

The indictment presented on 3 March 1945, accused Altin of anti-Soviet sentiments, treason to motherland, membership in the Omakaitse and rendering all possible assistance to the occupying powers in the capacity of rural municipality mayor.

The "plot" also mentioned his earlier activities as the rural municipality constable, company commander in the Defence League, and member of the Fatherland’s League. Two local inhabitants were listed as witnesses.

On 14 May 1945, the Military Tribunal of the NKVD Troops in the ESSR (presided by the MJS 1st Lieutenant Vinogradov, members Lieutenant Potapov and 2nd Lieutenant Zolkin) convicted Altin in accordance with Article 58-1 "a" of the Criminal Code and sentenced him to 10 years of corrective labour camp and 5 years of deprivation of rights, and confiscation of property. Of his earlier activities, only membership of the Defence League as company commander was mentioned in the verdict. Altin was released from imprisonment in 1954.

Hans Vaga, mayor of Taevere rural municipality in Viljandi County, was arrested on 30 November 1944. According to the regulation of arrest, he had worked as Taevere rural municipality mayor in 1930–1940, and been a member of the Fatherland’s League from 1938 and of the Defence League from 1939. Being hostile to the Soviet power, he became a traitor and, at the beginning of the German occupation, started active co-operation with the occupying powers.

After the departure of the Red Army in summer 1941, he resumed his post as rural municipality mayor and began to restore the bourgeois regime, was rural municipality mayor until 22 September 1944 and co-operated with the police to capture Soviet patriots: 8 farmers, who had been allotted land by the Soviet power, had been arrested following a complaint lodged by him personally; the land was returned to kulaks. In addition, he personally arrested a prisoner-of-war who had refused to work, and voluntarily joined the Omakaitse, where he was "assistant in economy matters to the battalion commander".

Aleksander Bachmann, arrested on the same day, was tried together with Vaga; he had been assistant rural municipality mayor in Taevere before 1940, and thus a direct subordinate of Vaga’s. The cases were united on 20 March 1945, as both men had been leaders of the Taevere rural municipality (Bachmann was appointed assistant rural municipality mayor in September 1941) and belonged to the local Omakaitse. 102 The indictment presented on 20 June 1945 concentrated, in both cases, on the activities during German occupation and did not mention their activities during the independence (although that too was known to the investigators). Four inhabitants of Taevere rural municipality were listed as witnesses.

On 26 July 1945 the Military Tribunal of the NKVD Troops in the ESSR (presided by MJS 1st Lieutenant Vinogradov, with Põld ja Kuzmichev as members), convicted both men in accordance with Article 58-1 "a" of the Criminal Code. In both cases, the verdict only mentioned membership of the Defence League of their activities during independence. Vaga was sentenced to 15 years of corrective labour camp with deprivation of rights for 5 years and confiscation of property, and Bachmann to a somewhat milder 10+5 and confiscation of property. Vaga was released from imprisonment in 1955 and Bachmann in 1954.

Kaarel Innus, mayor of Erra rural municipality in Viru County in 1930–1940, was arrested on 3 December 1944, and Captain Dubro, investigator of the NKGB Leningrad Oblast Administration, found that Innus had been a member of the Defence League, and mayor of Erra rural municipality from the beginning to the end of the German occupation, fulfilling all orders of the occupying powers, helping to rob the people and collecting taxes; in addition, he had been a SD agent, whose task it was to disclose partisans, escaped prisoners of war, etc.

The suspicion was based on the statements of Innus himself and the witness Oleg Peskov. The indictment presented on 29 October 1945 made no mention whatsoever of his activities during independence, the accusation consisted of Innus’ work as rural municipality mayor during the German occupation. Three local inhabitants were named as witnesses.

On 14 November 1945, the Military Tribunal of the NKVD Troops in the ESSR (presided by MJS Captain Tomashevskiy, with Sergeant Tilitsyn and 2nd Sergeant Ivashchenko as members) convicted Innus in accordance with Article 58-1 "a" and sentenced him to 10 years of corrective labour camp, 5 years of deprivation of rights and confiscation of property.

On 26 december 1944, Karl Kütt, former rural municipality mayor of Konguta, Tartu County, was arrested, and on 26 January 1945, also the cases of assistant rural municipality mayor Voldemar Metsik and Aleksander Kõiv were added to the same investigation file. Kütt was arrested due to co-operation with the German occupying powers who had "made him the rural municipality mayor of Konguta", in which capacity he had appropriated land from the farmers who had been allotted land during the Soviet occupation and returned it to kulaks. The evidence was based on the statement of the local inhabitant Henno Johandi.

In the case of Metsik, arrested on 21 November 1944, his being Konguta rural municipality mayor during the German occupation was also pointed out, as well as his membership in the Omakaitse and acting as commander during raids.109 Kõiv, arrested on 24 November, was only suspected of Omakaitse membership.

The indictment was presented to the three men on 26 January 1945. In Kütt’s case the "plot" included also his office as rural municipality mayor before 1940. The charges still concentrated on their activities during the German occupation. Kütt was rural municipality mayor until 1943, when the post was filled by Metsik, Kõiv was employed as "rural municipality mayor in land issues" in 1942–1943 [in fact, it could only have been a post of assistant to the rural municipality mayor – I. P.].

As usual in such cases, they were accused in fulfilling orders and instructions of the occupying powers in their capacity, collecting taxes and agricultural product rates, appropriation of land from those who had received it from the Soviet power, etc. The document listed three local inhabitants as witnesses.

On 13 July 1945, the Military Tribunal of the NKVD Troops in the ESSR (presided by MJS 1st Lieutenant Vinogradov, members Corporal Dubrovskiy and Sergeant Ivankin) convicted the men in accordance with Article 58-1 "a" of the Criminal Code and sentenced Kõiv to 15 and the other two to 10 years of corrective labour, with the deprivation of rights for 5 years and confiscation of property added in all three cases. Kõiv died in prison camp while serving his sentence, Metsik was released in 1955, and Kütt’s fate is not quite clear yet.

On 27 december 1944, Georg Laos, the former mayor of Kihnu (an island the Gulf of Riga), Pärnu County, was arrested as he had worked as Kihnu rural municipality mayor during the German occupation, joined the Omakaitse voluntarily and participated in arrests of Soviet activists in the forests of Kihnu.112 Later, the cases of other Kihnu men Peeter Kogri and Aleksander Rästas were also tied up to this investigation, as all three men had been connected to the activities of the Kihnu Omakaitse.

When Laos was interrogated, also his earlier terms as rural municipality mayor were discussed, and he said that he had been the mayor of Kihnu rural municipality in 1924–1927, 1937–1939 and in 1941–1944. The indictment, presented on 23 August 1946, did not mention Laos’ activities before 1940, and the main charge (against all three) was participation in the Omakaitse, in Laos’ case also the office of rural municipality mayor during the occupation was mentioned. Ten local inhabitants were listed as witnesses.

On 11 October 1946, the Military Tribunal of the NKVD Troops in the ESSR (presided by MJS 1st Lieutenant Pavlenko, with 2nd Lieutenants Sokolov and Aleksandrov as members) convicted the men in accordance with Article 58-1"a" of the Criminal Code and punished all three with 10 years of corrective labour with deprivation of rights for 5 years and confiscation of property.

In December 1944 – January 1945, the independence-time rural municipality government of Kõo in Viljandi County was arrested in corpore — the rural municipality mayor Jaan Ots and assistant rural municipality mayors Aleksander-Johan Vares and Jaak Kask. Their cases were bound together on 20 March 1945, because – according to the regulation of arrest – all three had been in the administration of the rural municipality also during the German occupation, they had appropriated land from poor farmers [who had received it from the Soviet power] and participated in the arrests of the Soviet patriots.

The regulation of arrest included also the activities at the time of independence in case of both Ots (office of rural municipality mayor, membership in the Defence League and the Fatherland’s League, participation in the War of Independence) and Kask (participation in the War of Independence, membership in the Defence League, office of assistant rural municipality mayor). In all three cases, most items in the list of suspected crimes concerned their activities during the German occupation.

On 10 May 1945, the men were presented an indictment, which only presented independencetime activities in case of Ots, and was in the "plot" part limited to membership in the Defence League and the Fatherland League (i.e. totally ignoring his office as rural municipality mayor). Four inhabitants of Kõo rural municipality were listed as witnesses.

On 13 June 1945, the men were tried by the Military Tribunal of the NKVD Troops in the ESSR, presided by MJS Major Pyotr Ukhuta and with Lieutenant Lysenko and 2nd Lieutenant Zaitsev as members. In accordance with Article 58-1 "a" of the Criminal Code, Ots and Kask were sentenced to 10+5 with confiscation of property; Vares was sentenced to 8+3 with confiscation of property in accordance with Article 58-3 of the Criminal Code. Vares died in the prison hospital in Karaganda Oblast on 26 August 1947 and was buried in the graveyard of the 4th division of the Karlag. Kask and Ots were released after Stalin’s death.

Although not from the same period, also the story of Johannes-Alfred Pärtma is worth of consideration as a colourful example. Pärtma was a farmer and in 1934–1937, assistant mayor of Tuhalaane rural municipality in Viljandi County, and mayor of the same rural municipality in 1937–1940. He was also commander of the local unit of the Defence League, and therefore bound to become leader of the local Omakaitse unit in 1941. In 1944, Pärtma took to the woods, but came out and was legalised in 1946.

He was in the deportation lists of 1949, but hid in the woods again. In 1953 he was legalised again, but "continued to conceal his past" and worked as chauffeur in a kolkhoz. On 20 July 1955 Pärtma was finally arrested, and the indictment was finally presented on 17 October, the main charges being participation in the Defence League and the Omakaitse.

On 8 November 1955 the investigation was suspended by a regulation of Colonel A. Polev, Prosecutor of the 8th Naval Fleet, as Pärtma was found to be subject to amnesty under the enactment "On Amnesty to the Soviet Citizens who Collaborated with the Occupying Powers during the Great Patriotic War in 1941–1945" from 17 September 1955, and subsequently released. Two weeks later (on 23 November) the previous enactment was declared null and void, Pärtma was arrested once more and everything started over. This time, the investigation ended with a verdict: on 21 February 1956, the Military Tribunal of the 8th Naval Fleet (presided by MJS LieutenantColonel Stukanov, with Lieutenant-Colonel Ivanov and 3rd Rank Captain (Major in Soviet Navy) Kalugin as members), sentenced Pärtma to 25 years in corrective labour camp, with deprivation of rights for 5 years. On 26 May 1956, the Supreme Court of the USSR commuted the sentence to 10 years of corrective labour.

Conclusion

A considerable part of the political and social elite of Estonia was repressed – imprisoned, deported, or executed – during the first year of the Soviet occupation: 4/5 of the former Estonian Heads of State, 2/3 of the former Ministers, half of the members of the last Riigikogu, etc. Most of them were killed within the next couple of years and only very few managed to return home in the years following the war. When returning to Estonia in autumn 1944, the security agencies of the Soviet Union continued where they had left off, but with new target groups which had emerged during the German occupation.

Before the war, people were usually not convicted for working on a certain post or belonging to some representative body (although there were cases of both), even if such evidence was found out in the course of the investigation. The charges may have been based on acts proceeding directly from one’s official duties (as participation in the trials of communists in case of judges). But in most cases, membership in "organisations hostile to the people", such as the Defence League or the Fatherland’s League, formed the basis for conviction or arrest.

When comparing accusations from before and after the war, some differences are evident. Accusations in collaboration with the German occupying powers are clearly the main issue. Laws of the Soviet Union made it possible to convict everybody who had held any office during the occupation or even been present in the occupied territory (not having left the territory could be interpreted as treason to motherland). What is most tragic about the whole thing is that there where indeed those who collaborated with the occupying power, and that their readiness to co-operate was in turn caused by the repressions of the Soviet occupying power.

Professional activities during independence (provisionally, we count also membership in representative bodies and the honorary office of rural municipality mayor as professional activities here) received much less attention in accusations made after the war, but the charges of participation in the War of Independence and membership in the Defence League were widespread. At times, professional activities were still an issue, and here some distinct tendencies are evident.

It was in case of former ministers and county governors that the issue of former profession was taken up. Yet this was not the case with members of parliament and public servants. In case of ministers and county governors there is clear statistical evidence that the whole target group was eliminated systematically — everyone who could be captured was arrested. The small amount of arrests was usually due to the fact that there were not many left to arrest.

It is important to notice that professional activities are included in a court’s verdict in one case only, and are never presented in the part of the indictment concerned with charges. If at all, they are mentioned in the "plot" of the indictment. Why is this so? I suggest that the reason might be in the working methods of the security agencies.

First, a cause for arrest had to be found, i.e. something had to be written down. And data about employment was the easiest to find, there was no need even to visit the archives, as the data was available in the Riigi Teataja (State Gazette) and widespread information booklets. For instance, the archival notice in the investigation file of Viktor Pihlak was drawn up on the basis of a booklet "Public Figures of Estonia", published in 1932, as well as telephone catalogues and newspapers. If other, "better" and more appropriate excuses for charges were discovered in the course of investigation, the original ones were simply neglected.

The above might seem to be an issue of minor importance, as for a human being there was not much difference for what exactly he was sentenced to prison camp – considering that most of the sentences were unjust in view of legal norms of the rule of law.

The most widespread charge was that of membership in the Omakaitse, especially with elite in localities (e.g. rural municipality mayors). If membership in the Omakaitse was evident, there was absolutely no need for additional evidence, for that guaranteed conviction in any case. The local Omakaitse leaders and the rural municipality leaders from the time of the German occupation were pursued with special fervour, because these posts were understandably held by the more educated and socially active people, i.e. the local elite. In most cases, the same people had been in the rural municipality administration also before 1940, and this is why they returned to power in the summer and autumn of 1941.

I think it was a priority for the occupying powers to render harmless this kind of elite as a potentially dangerous part of the population. That they were dangerous had been proved by the summer of 1941. In 1944–1945, about 50 former rural municipality mayors were captured, and that is more than during a period of the same length in 1940–1941.

Perhaps the occupying powers before the war did not succeed in apprehending everyone they wished, especially as part of the men were hiding in the forest, but on the other hand, there were men in the forest also in 1944–1945, and by far not all of them were caught. In the summer and autumn of 1941 these where the men who started to organise resistance and – to resort to the rhetoric of the security structures – "restore the bourgeois regime" locally. Thus, the threat these men represented, and the need to neutralise them first of all had become clear.

Public servants, on the other hand, were not considered a great hazard. A public servant is loyal to his employer despite the change of regime – that was another lesson learned from the alternation of occupying powers. Thus, the public servants whose only fault would have been their employment as public servants during independence, were not repressed, especially as the highest tops of the Estonian population had been liquidated almost completely already before the war.

As we know, the Criminal Code of the Russian SFSR from 1926 also stipulated conviction for counter-revolutionary and anti-Soviet activities, i.e. for performing public service in the "bourgeois" Republic of Estonia. Nor should we forget that part of the public servants were obviously spared simply due to the need to retain a certain continuity of knowledge and experience.

In the light of these conclusions, it cannot be claimed that repressions of individuals in 1944–1953 had a direct connection with the repressed individual’s professional activities in the Republic of Estonia. Nor can the contrary be claimed without reservations, at least in case of certain target groups, as the earlier occupation of the victims was usually known to the security agencies, and the logic by which both the investigating and the judicial system worked is, just as before, largely a matter of guessing.

This article is previously published in a memorial collection “At the Will of Power. Selected articles”. it contains the most important and best part of his research. The book can be purchased online from the National Archives of Estonia, Apollo and Rahva Raamat.

Indrek Paavle (born in 1970) has graduated from the Department of History in the University of Tartu in 1998 (cum laude) and defended a master thesis on topic “The institution of the Rural municipality in Estonia 1940-1941” and he defended his doctoral dissertation in 2009 (Sovietisation of Local Administration in Estonia 1940–1950). Indrek Paavle was awarded the Science prize of Lennart Meri in 2010 for his dissertation. In 2012 he was awarded the 15 000 euro grant for compiling Otto Tief's academic biography. He has worked in the National Archives, the Estonian Foundation for the Investigation of Crimes against Humanity and the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory. He was one of Estonia’s most prominent historians, who tragically perished in 2015.

Literature:

Indrek Paavle, „Fate of the Estonian elite in 1940–1941,“ Estonia 1940–1945: Reports of the Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity (Tallinn: Inimsusevastaste Kuritegude Uurimise Eesti Sihtasutus, 2006), 391–408.

Jüri Ant, Eesti 1920: Iseseisvuse esimene rahuaasta (Tallinn: Olion, 1990), 25–30.

Viljar Valder, „Eesti Raudteevalitsuse fond 1941–1943“ (bakalaureusetöö, Tartu Ülikool, 2006), 9.

VNFSV Kriminaalkoodeks: muudatustega kuni 1. detsembrini 1938. Ametlik tõlge (Tallinn: ENSV Kohtu Rahvakomissariaat, 1940), 6.

Metsavennad Suvesõjas 1941: Eesti relvastatud vastupanuliikumine Omakaitse dokumentides, koostanud Tiit Noormets, Ad Fontes, 13 (Tallinn: Riigiarhiiv, 2003), 80–84.

Sources:

Aleksander Roosilehe uurimistoimik. Arreteerimismäärus, 4.7.1945, RA, ERAF.130SM.1.13191, 3

Aleksander Roosilehe uurimistoimik. Süüdistuskokkuvõte, 15.3.1946, RA, ERAF.130SM.1.13191, 34–35.

Aleksander Roosilehe uurimistoimik. Väljavõte erinõupidamise protokollist, 4.1.1947, RA, ERAF.130SM.1.13191, 38.

Aleksander Tulbi uurimistoimik. Arreteerimismäärus, 12.12.1944, RA, ERAF.129SM.1.26615, 2.

Aleksander Tulbi uurimistoimik. Süüdistuskokkuvõte, 30.5.1945, RA, ERAF.129SM.1.26615, 85–86.

Aleksander Tulbi uurimistoimik. Väljavõte erinõupidamise protokollist, 8.9.1945, RA, ERAF.129SM.1.26615, 87.

Aleksander Veiderma uurimistoimik. Arreteerimismäärus, 10.11.1944, RA, ERAF.130SM.1.11455, 1.

Aleksander Veiderma uurimistoimik. Kohtuistungi protokoll ja otsus, 15.3.1945, RA, ERAF.130SM.1.11455, 41–43p.

Aleksander Veiderma uurimistoimik. Süüdistuskokkuvõte, 21.2.1945, RA, ERAF.130SM.1.11455, 35–36.

August Altini uurimistoimik. Arreteerimismäärus, 27.11.1944, RA, ERAF.130SM.1.11359, 2.

August Altini uurimistoimik. Kohtuotsus, 14.5.1945, RA, ERAF.130SM.1.11359 (järelevalvetoimik), 8.

August Altini uurimistoimik. Süüdistuskokkuvõte, 3.3.1945, RA, ERAF.130SM.1.11359, 38–39.

August Hanko uurimistoimik. Arreteerimismäärus, 16.4.1945, RA, ERAF.130SM.1.14667, 2.

August Hanko uurimistoimik. August Tõllassepa ülekuulamise protokoll, 14.4.1945, RA, ERAF.130SM.1.14667, 26–27.

August Hanko uurimistoimik. Süüdistuskokkuvõte, 17.7.1945, RA, ERAF.130SM.1.14667, 29–30.

August Hanko uurimistoimik. Ülekuulamisprotokoll, 16.4.1945, RA, ERAF.130SM.1.14667, 12–13.

August Leppiku uurimistoimik. Arreteerimismäärus, 26.11.1944, RA, ERAF.129SM.1.6887, 4.

August Leppiku uurimistoimik. Kohtuotsus, 31.5.1945, RA, ERAF.129SM.1.6887, 50–51.

August Leppiku uurimistoimik. Süüdistuskokkuvõte, 17.5.1945, RA, ERAF.129SM.1.6887, 38–39.

August Leppiku uurimistoimik. Ülekuulamisprotokoll, 23.11.1944, RA, ERAF.129SM.1.6887, 14 jj.

Bernhard-Aleksander Roostfelti uurimistoimik. Arreteerimismäärus, 7.11.1944, RA, ERAF.130SM.1.9924, 2.

Bernhard-Aleksander Roostfelti uurimistoimik. Süüdistuskokkuvõte, 28.2.1945, RA, ERAF.130SM.1.9924, 58–59.

Eduard Jõerüüdi uurimistoimik. Arreteerimismäärus, 13.9.1945, RA, ERAF .129SM.1.16551, 1.

Eduard Jõerüüdi uurimistoimik. Kohtuotsus, 13.9.1945, RA, ERAF.129SM.1.16551.

Eduard Jõerüüdi uurimistoimik. Süüdistuskokkuvõte, 26.11.1945, RA, ERAF.129SM.1.16551, 66–69.

Eduard Peedoski uurimistoimik. Arreteerimismäärus, 17.11.1944, RA, ERAF.129SM.1.6204, 1.

Eduard Peedoski uurimistoimik. Kohtuotsus, 31.3.1945, RA, ERAF.129SM.1.6204, 45–46.

Eduard Peedoski uurimistoimik. Süüdistuskokkuvõte, 28.1.1945, RA, ERAF.129SM.1.6204, 34–35.

Friedrich Vendachi uurimistoimik. Arreteerimismäärus, 24.5.1951, RA, ERAF.130SM.1.4510, 3.

Friedrich Vendachi uurimistoimik. Kohtuotsus, 7.8.1951, RA, ERAF.130SM.1.4510. 99–100.

Friedrich Vendachi uurimistoimik. Süüdistuskokkuvõte, 21.7.1951, RA, ERAF.130SM.1.4510, 80–81.

Georg Laose jt uurimistoimik. Arreteerimismäärus, 23.8.1946, RA, ERAF.129SM.1.184, 125–128.

Georg Laose jt uurimistoimik. Arreteerimismäärus, 25.12.1944, RA, ERAF.129SM.1.184, 31.

Georg Laose jt uurimistoimik. Kohtuotsus, 11.10.1946, RA, ERAF.129SM.1.184, 156–157.

Gustav Viardi uurimistoimik. Arreteerimismäärus, 4.11.1950, RA, ERAF.129SM.1.25759, 3–4.

Gustav Viardi uurimistoimik. Kohtuotsus, 30.3.1951, RA, ERAF.129SM.1.25759, 99–100.

Gustav Viardi uurimistoimik. Süüdistuskokkuvõte, 16.3.1951, RA, ERAF.129SM.1.25759, 75–77.

Hans Vaga ja Aleksander Bachmanni uurimistoimik. Arreteerimismäärus, 29.11.1944, RA, ERAF.130SM.1.13684, 4.

Hans Vaga ja Aleksander Bachmanni uurimistoimik. Kohtuotsus, 26.7.1945, RA, ERAF.130SM.1.13684, 74–76.

Hans Vaga ja Aleksander Bachmanni uurimistoimik. Määrus uurimisasjade ühendamise kohta, 20.3.1945. RA, ERAF.130SM.1.13684, 2.