Russia

Communist Dictatorship in Russia (1917-1991)

In both relative and absolute terms, Russia is one of the countries having suffered most in the hands of communists. The communist coup of 1917 and power consolidation during the civil war destroyed the existing Russian way of life, wiped away the thin layer of intelligentsia that had kept the country on the path of civilization and rendered the Russian people in the hands of communists who exploited them to spread war and destruction to other countries.

The attempt to build a communist empire ended in failure and Russia sunk into one of the deepest crises of its history in the 1990s. The number of victims of communism in Russia is subject to various estimates. According to the „Black Book of Communism”, some 20 million perished, while academic A. Yakovlev claims that the communist-triggered civil war alone claimed some 13 million lives, topped by 5.5 million who starved to death in the early 1920s and the 5 million famine dead of the 1930s.

According to Yakovlev, 20-25 million people were executed or died in prison camps as a result of communist terror. With millions killed by mass deportations, the number of victims could be between 50-60 million. This figure does not include the estimated 27 million Soviet lives lost in the Second World War that Stalin helped to unleash.

Russia has yet to overcome the demographic, social and economic disaster inflicted by communism.

Historical overview

In February 1917, the Russian Empire was the largest country of the world, covering a total of one-sixth of the Earth’s land surface in Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It had a population of roughly 170 million people. Politically, Russia was a monarchy, ruled by tsar Nicholas II. In 1914, when World War I broke out, Russia’s industrial production ranked fifth in the world and fourth in Europe; but stood somewhere in the middle as regards general economic development.

Participation in the First World War led to economic difficulties, inflation and serious problems of supplying the population with food. At the beginning of 1917 massive strikes broke out. On 2 March 1917[1] Nicholas II abdicated and the Provisional Government came to power. This is known as the Bourgeois Democratic Revolution.

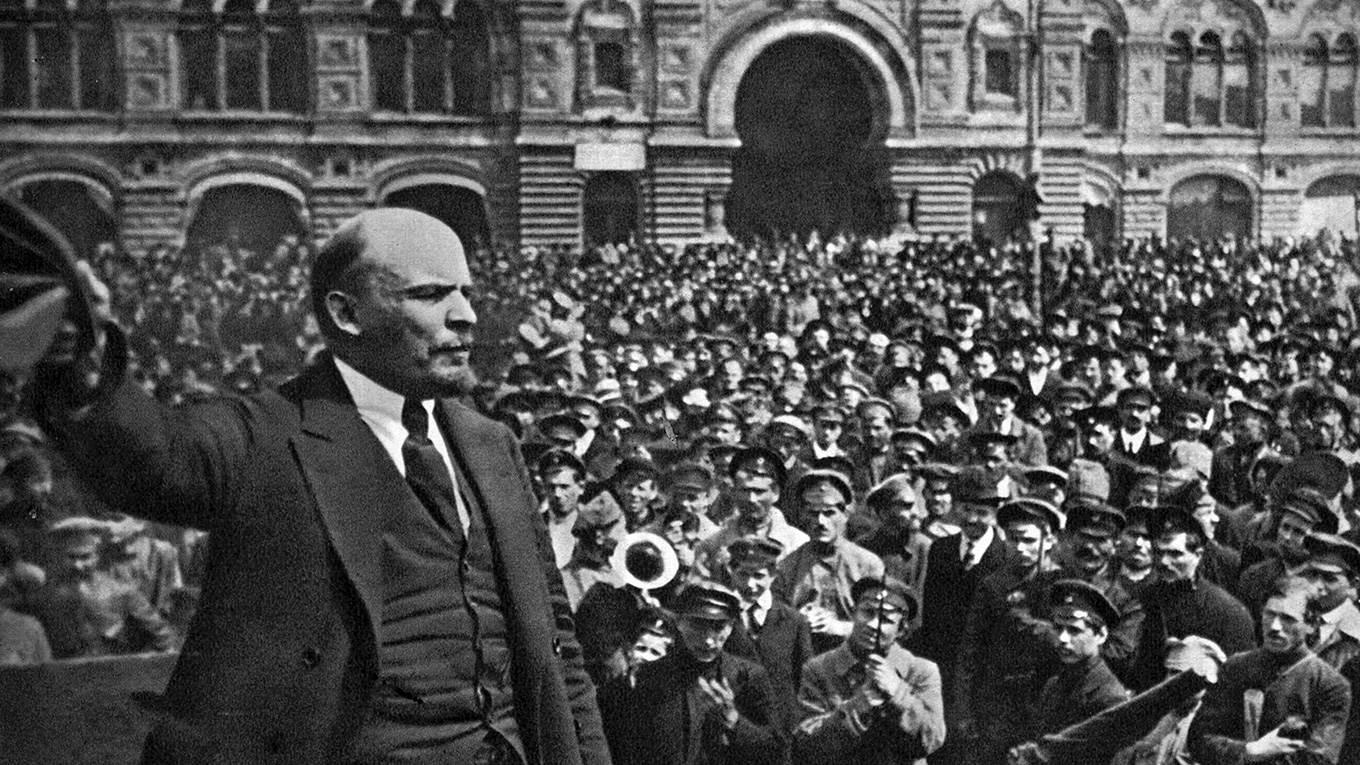

At the same time, far left parties and groups were also operating in Russia; their ideology was based on Marxist doctrines of reorganising the society. The most radical and persistent among them was the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), with Lenin at its head. It was Lenin and his party that toppled the Provisional Government in the 1917 October Revolution, and seized and usurped power.

What followed was the long-term struggle by Lenin and the Bolsheviks to cement and spread their power across the whole country; at the same time opposition to the Bolshevik rule grew steadily. In September 1918, the Bolsheviks launched the Red Terror campaign, in which large numbers of people were arrested and shot in order to scare others into submission. Finland, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia broke apart from Russia and became independent states. Ukraine, Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan and several countries in Asia declared independence as well. However, in the course of the heated battles of the Civil War the Bolsheviks were able to bring the latter countries under their influence and make them part of the newly established Soviet empire, where the internal borders were fixed on the basis of ethnic borders. Although officially the socialist nation states were independent, it was but an illusion.

They were used to build a new type of centralised state. The creation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was declared officially at the First All-Union Congress of Soviets on 30 December 1922. The USSR consisted of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic and Transcaucasian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic. As the borders of the Central Asian nation states were settled in the 1920s and 1930s, more soviet socialist republics emerged: Turkmen SSR, Uzbek SSR, Tajik SSR, Kirghiz SSR and Kazakh SSR.

The Soviet occupation in 1940 led to the establishment of Latvian SSR, Lithuanian SSR, Estonian SSR and Moldavian SSR.

This is how the USSR restored the greatness and power of the empire, but the aim now was to spread the communist rule to its neighbours as well. On 30 November 1992 the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation characterised the Soviet political regime as follows: „For a long period in the country there was a regime of unlimited power based on violence of a small group of communist functionaries united in the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), headed by that body’s General Secretary.”

By the end of the 1980s the population of the USSR had grown to 286.7 million. The years 1989-1991 saw the gradual collapse of the Soviet system. There was a national awakening in the republics and independence movements emerged. One union republic after another declared independence and left the USSR. A deep political and economic crisis led to coup d’état in August 1991, when the old-timers among the top echelons of the CPSU, the military and KGB attempted to turn around the democratic reforms and seize power. The failure of the coup brought along the collapse of the communist system.

Politics

The building of the Soviet political system meant a complete disruption of the social relations existing previously in Russia, as well as continued struggle against the so-called remnants of the past. The enormity of the tasks and the breadth and depth of the changes undertaken by the Bolsheviks simply required a brutality in their implementation. In order to follow the Marxist doctrines, the new order to be built was going to be in conflict with the basic instincts of the human society.

The measures proposed by the Marxists for reorganising the social and economic relations included expropriation of land ownership, abolition of inheritance rights, educating children on a communal basis and an equal obligation on all members of society to work.[1]

The purpose of these measures was to do away with the traditional family and eradicate private ownership instincts. When the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia in 1917, they faced the task of „re-shaping the human material” and creating a new type of person. It was entirely clear for Lenin that doing away with classes and class differences was the fastest way to building a communist society. In 1919 Lenin formulated the task of „abolishing the difference between factory worker and peasant, to make workers of all of them”.

Violence became the means of implementing the communist doctrine. The power rested with the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), later Communist Party of the Soviet Union, led by its Central Committee and Politburo. Special agencies of state security were created for carrying out mass repressions: Cheka – OGPU – NKVD - NKGB – MGB – MVD – KGB.

In March 1918 the Soviet government moved from Petrograd to Moscow. Thus, Moscow became the capital city and seat of the apparatus of power. All power was concentrated into the hands of the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) (from 1925 All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), from 1952 Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU)). The Central Committee was elected by the Communist Party Congress, the Central Committee elected the Politburo and Secretariat. During the period of 1952–1966 the CPSU Central Committee Presidium replaced the Politburo.

From the outside everything looked proper – there was the executive branch of power or the government called the Council of People’s Commissars (after 1946 Council of Ministers) and the legislative branch, the Central Executive Committee (after 1938 the Supreme Soviet of the USSR), formed by general and direct elections as the organ of people’s power.

In reality all decisions were made in the Politburo and Secretariat of the Central Committee and were formulated only after that as acts of the organs of state power, for according to the constitution the right to adopt such acts rested with these bodies. So, everything was done just as prescribed by the „Soviet order”. The Politburo secretly held actual power, but did not wish to show their real role in decision-making, thus, for the rest of the world, the decisions were made to look as if the Council of Ministers or the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet had adopted them.

Immediately after the Bolsheviks seized power in 1917, they created the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission, better known as the Cheka (or Vecheka). It was the organ of state security, directly subordinated to the Politburo of the Central Committee. The structure remained the same, even if the name changed as time went by. From 1922 the name was Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU), from 1934 – People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD), in 1941 and again from 1943 – People’s Commissariat for State Security (NKGB), from 1946 – Ministry of State Security (MGB), from 1954 until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 – Committee for State Security (KGB). The secret police implemented the state’s penal policy and were in charge of the huge system of forced labour camps (known as Gulag from 1930).

Following World War II, the experience of the Soviet political system and the principle of secret leadership of the Communist Party was emulated in the Eastern European countries, in which communist regimes were established with the help of the Red Army and the staff of the Soviet secret services.

[1]K. Marx, F. Engels. Manifesto of the Communist Party. Tallinn, 1974, pp 60–61.

Repressions

Since seizing power in 1917 the communists have always used violence and forced labour to support their regime. All privileged groups of the former society, as well as anyone who thought differently became victims of persecutions and repressions.

The church came under vicious attacks, and repressions were carried out against representatives of all denominations. The Bolsheviks were dead against religion and wanted to eradicate faith and freedom of conscience for ever, so as to make room for a jubilantly atheistic society. The political rights of the representatives of the former wealthier classes, the so-called former people (civil servants, tradesmen, entrepreneurs) were restricted.

The development of a society of „new Soviet people” started immediately and ideological re-educating was in full swing. This is also where the Soviet pedagogy has its beginnings: although they never went as far as removing the children from their families, the children were immersed in communist ideology at school and were expected to unquestioningly accept the ideology. In 1930 Lenin’s plans of „collectivization” and „liquidation of the kulaks as a class” were finally carried out, effectively destroying the peasantry. Now nothing stood in the way of physically eliminating all those who did not fit in the Soviet ideological model.

The ideological change was completed in the Soviet Union by the middle of the 1930s, when the romantic ideas of proletarian internationalism were overshadowed by the strengthening of imperial policies. Stalin’s isolationism led to the phenomenon of Soviet exceptionality or a kind of „Soviet Nazism”. Nazism in this context did not mean tribal or ethnic belonging but a certain unity of the Soviet peoples. At the same time nations of the neighbouring countries were considered hostile. This became particularly evident during the Great Terror/Great Purge of 1937-1938.

It was the class doctrine underlying the communist ideology that caused the Great Terror. The desire to create a classless society pushed Stalin towards an accelerated and violent solution in the mid-1930s. Stalin took word-for-word the euphemistic phrase of „eliminating class differences”, found in the party guidelines.

Similar repressions were part and parcel of the horrendous collectivization of 1930-1931: using „troikas” in OGPU local departments, shootings and deportations based on numbers given by Moscow. Nowadays some are trying to explain the mass purges that swept through the country in 1937 as if they were a natural catastrophe, a raging storm that could not be predicted or prevented. This is not true, the terror of 1937-1938 was premeditated, a carefully planned and implemented crime of the authorities against their own people. These crimes were committed because of the ideological doctrine on which the world view of the Bolsheviks was built and undoubtedly because the perpetrator was Stalin himself.

Building socialism in one country inevitably meant that the country became a „stronghold under siege” in a hostile environment, leading mainly to two types of repressions. Persecutions were aimed at the so-called traditional class enemy: representatives of the former classes and peasants who had become rich during the Soviet period – the kulaks. Also repressed were those who had some foreign connections. For example, peoples living in the Soviet Union, whose countrymen had an independent state right across the border.

Stalin held them as potential enemies, in the NKVD documents they were called a „human pool of foreign spies” and it was only inevitable that with the beginning of „national operations” such people were labelled as ethnic contingents. And it was not only representatives of these nations that came under this category, but also anyone who had something to do with those states, whose relatives lived there or who had correspondence with inhabitants of those states. So, repressions were targeted against people belonging to the two main categories, based on class or ethnicity. Political affiliation was another reason for persecutions.

Anyone who did not belong to Lenin’s party was a target: left- and right-wing Esers, Mensheviks, Anarchists, members of the Bund group, but also opposition within Lenin’s own party – „Right Opposition”, supporters of Zinoviev, Trotsky and „Workers’ Opposition”. Although they were members of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks)/All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), they did not share Stalin’s policies. Thus, the Great Purge meant persecutions against anyone who came under the category of real or potential enemy, who could become an enemy or at least could be suspected of becoming an enemy.

Stalin started the mass terror campaign with the aim of exterminating physically his political opponents and replacing the old revolutionary cadres with representatives of the new Soviet intelligentsia, who had already grown up in the atmosphere of Stalinist dogmas. The governing elite was now entirely Soviet elite.

The aim of the Great Terror was to establish across the country complete unity of thought, so that no one dared dispute the authority and leadership of Stalin. And true enough, the Great Terror caused such fear in the Soviet people that allowed the system to exist for a long time. It was like an injection of the vaccine of fear. Clearly, it was no longer safe to say anything that parted with the official doctrine and Stalinist ideas, as had been the case before. Such behaviour, as well as contacts with foreign countries and foreigners had become deadly.

In complete harmony with the communist doctrine, the Kremlin organised in the occupied Baltic states mass deportations, based on social status and class in 1941, arrested and shot those who opposed the Soviet rule in 1944-1947 and finally carried out a ruthless campaign of „collectivization”, deporting tens of thousands of country people in 1949. Armed resistance to the Soviet regime lasted in the Baltic states for about a decade (1944-1953), bearing all the features of a struggle for national independence. The organs of the Soviet penal system were used to supress the resistance: security services, militia, regular army and internal troops.

The scope of Soviet repressions is so huge that it is difficult to fathom. More than six million people were arrested and one million shot in the period 1921-1953. Another six million were deported to the outermost regions of the country. Whole nations were re-settled, depriving them of their ethnic and governmental structures: the Germans, Kalmyks, Chechens, Ingush, Balkars, Karachays, Crimean Tatars all suffered such fate.

In comparison with the Stalin era repressions by Khrushchev and the subsequent Soviet leaders were considerably more modest on scale. However, during the period from the 1960s to 1980s dissidents were persecuted ruthlessly, and people who stated publicly their opposition to the Soviet rule were sent to prison or a mental hospital by the KGB.

Economy

According to the economic rationale of Lenin and his party a new, socialist mode of production was to emerge from the capitalist mode of production, where the means of production are owned by the society, private land ownership has been abolished, transport has been nationalised and the state is in charge of production and distribution of benefits.

When the Bolsheviks came to power, they nationalised all large-scale industries and took over the landed estates from the nobility. During the Civil War a system of providing food to the cities was introduced, whereby the peasants had the obligation to supply the food and any surplus food was requisitioned by force.

By theory, the War Communism and state distribution system established by the Bolsheviks ought to have brought the country closer to the ideals of socialism, where all were equal. However, the reality turned out to be more complicated than political doctrines. To avoid losing power, the Bolsheviks were compelled to take a step back and come out with „New Economic Policy” or NEP in 1921. They allowed private capital and private entrepreneurship to exist in limited form, which also meant that certain class distinctions and differences were maintained in the way of life, manner of thought and behaviour of people belonging to the different strata of the society.

Despite the temporary setback the Bolsheviks continued to ardently pursue their goal. In 1925 a decision was made about industrialisation: heavy industry and the manufacturing of means of production were to become priorities. NEP was abandoned by using economic coercion and repressions. Collectivization of agriculture and forced integration of individual landholdings into collective farms began in 1930.

The Soviet economy was a type of command economy, managed by orders coming from the top echelons of power, and five-year plans were used to direct economic development. The State Planning Committee or Gosplan was established in 1921 as the main agency organising the economy.

The main problems with the Soviet economic model were the attempt to make everybody socially equal and the lack of sufficient stimuli to increase labour productivity. The Soviet propaganda machine kept indoctrinating the masses with the idea of collectivism, but in reality, the Soviet people were the product of adapting to the system. The Soviet authorities attempted for many years to eradicate private ownership instincts in the people, but the result was a flagrant failure. The tendency to steal state property was common to all social strata, from workers to ministers.

The Soviet system tried to re-shape human nature, a purely idealistic endeavour. When toiling away at their own allotment the Soviet people showed true love for work and their productivity skyrocketed. However, in the Soviet state production system the labour productivity lagged many times behind that of the capitalist countries. Incidentally, the same phenomenon continues in modern Russia.

The reasons lie in the behavioural instincts of the Soviet people: the mentality of being socially and mentally dependent, political passiveness and fear of making independent decisions, avoiding personal responsibility, fear of exclusion from the society, conformism and unconditional acceptance of the opinion of the majority, and naturally, xenophobia and chauvinism hidden, but simmering under cover of fear.

The more „free work”[1] was praised and glorified in the Soviet Union, the more the ordinary Soviet citizens tried to avoid working. The mandatory nature of work was part of the Soviet doctrine. In addition, work could also be used as a form of punishment. During the Khrushchev and Brezhnev era refusal to work did not only indicate a deviation in behaviour, but was also a form of political protest by citizens. Through this, Soviet people demonstrated their acceptance of the totalitarian regime on the one hand, and a tendency to a certain obstinacy or anarchy, if control was loosened, on th

[1]Official propaganda used the words of Stalin: „Work in the Soviet Union is a matter of honour, a matter of glory, a matter of courage and heroism.”

Society and culture

The new proletarian culture promoted by the Bolsheviks turned into a completely unique phenomenon in the 1920s, characterised by innovative approaches, where creative artists were no longer confined to former ways of doing things and obsolete dogmas. However, strict censorship soon dwarfed innovation and was replaced by a propagandist style that used artistic means to support the party line.

There was a reason why monumental art was called „monumental propaganda” already in the early years of the communist regime. In 1932 the various literary groups were brought together into the Union of Soviet Writers under the watchful eye of the party. Socialist realism was the single method allowed for writers.

The unity of thought that gained prominence by the mid-1930s curbed artistic freedoms and led to the emergence of Soviet Classicism. All creative pursuits and experiments were condemned and subjected to punishment. Any deviation from the established Soviet canon was denounced as „formalism”.

The Soviet „uniqueness”, exceptionality and pride introduced by Stalinist propaganda was actually deeply rooted in nationalism, which characterised every single nation forming part of the Soviet Union. This was the primal fear of strangers: „they” must be completely absorbed into the Soviet „us”, which qualitatively surpasses all other nations that continue to live under capitalism.

Dmitri Shepilov’s article „Soviet Patriotism”, published in the main communist daily Pravda, became the programmatic document, which claimed superiority of the „Soviet people” over all other peoples of the world.[1] It said it all: „Soviet patriotism is like a gold nugget formed from the most glorious and honourable traits of our people. The name of the Great Stalin stands as a symbol of the colossal might, victories, fame and new reconstruction plans of the people.”[2] In addition to promoting the archaic „leader cult” in this article, Shepilov adds an important postulate: „The Great Stalin says that „the humblest Soviet citizen, being free from the fetters of capital, stands head and shoulders above any high-placed foreign bigwig whose neck wears the yoke of capitalist slavery”.”[3]

It was hardly an accident that in that same year of 1947 Soviet citizens were banned from marrying foreigners (the ban was abolished in 1953). New laws regulating marriage and family matters had been adopted in 1943 and 1944; these were considerably more conservative in comparison with earlier laws (e.g. the 1926 Code of Laws on Marriage and Divorce, the Family and Guardianship) and reintroduced regulation and interference of the state in family matters. The Bolsheviks had to give up Marxist postulates and return to more traditional principles concerning family issues. However, the party line remained unchanged as regards private property.

Soviet leaders who came after Stalin modified some of their political rhetoric, but changed nothing in reality. In the report to the 22nd Congress of the CPSU Nikita Khrushchev declared: „A new historical community of people of different nationalities possessing common characteristics – the Soviet people – has taken shape in the U.S.S.R. They have a common socialist motherland, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, a common economic basis, the socialist economy, a common social class structure, a common world outlook – Marxism-Leninism – a common goal, that of building communism, and many common features in their spiritual make-up, in their psychology.”[4]

A decade or so later Leonid Brezhnev developed this idea further in his speech to the 24th Congress of the CPSU: „During the years of socialist construction a new historical community of people, the Soviet people, has been formed. New, harmonious relations of friendship and cooperation have developed between the classes and social groups, nations and nationalities. These relations have been formed in collective labour, in the effort to bring about socialism, and in the battles fought in defence of socialism.”[5]

After Stalin’s death the Soviet society and culture started to gradually open up to the rest of the world. There were more creative freedoms, but real freedom was out of the question under state censorship. The best Soviet artistic achievements are to be found in the 1920s and 1960s, the periods when censorship was not so strict and repressions by the Communist Party fewer.

[1]Д Т. Шепилов. Советский патриотизм. Pravda, 11 August 1947.

[2]Ibid.

[3]Ibid. Shepilov quotes Stalin’s report to the 18th Congress of the CPSU in March 1939. J. V. Stalin. Leninismi küsimusi. Tallinn, 1952, p 550.

[4]22nd Congress of the CPSU. Verbatim report I. Tallinn, 1962, p 145.

[5]L. Brezhnev. Report of the Central Committee of the CPSU to the 24th Congress of the CPSU, 30 March 1971. Tallinn, 1971, p 91.

Militarism

The Soviet state emerged while World War I was still ongoing. During the German advances at the front in February 1918 Lenin issued a decree, titled „Socialist Homeland is in Danger!”. This was a sign of a new ideological construct of „Soviet patriotism”, which was inevitably accompanied by militarism in a situation where the Soviet system stood alone against the rest of the world. Soviet propaganda used every possible means to emphasise the importance, even sanctity of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army as the sole defender of the homeland against foreign enemies.

In the 1920s the Red Army was relatively weak and the main focus of the then propaganda was on the threat coming from the „capitalist neighbours” who were supposedly preparing for military aggression against the Soviet Union. At the same time, the Red Army was seen as the principal force of foreign intervention, should the communist parties of other countries, led by Comintern, be able to organise a revolution and seize power. The participation of the Soviet military in the Spanish Civil War of 1936-1939 is a clear example of how such plans were carried out.

By the end of 1930s the Red Army had grown considerably stronger and the military and political situation in Europe had moved in a direction beneficial for the Kremlin. Major European powers were opposing each other and Stalin chose Hitler as his ally, which led to signing a document defining each country’s spheres of influence (the secret protocols of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact). Next, the new allies, Stalin and Hitler divided Poland between themselves and Stalin started preparations for occupying and sovietisation of other neighbouring countries. The Red Army was used to conquer the territories. Aggression against Finland in 1939 resulted in the expulsion of the Soviet Union from the League of Nations. Germany and the Soviet Union are both equally responsible for starting World War II.

However, by 1941 it was clear that the Soviet Union and Germany had different interests and their contradictions were increasing. When Hitler attacked the Soviet Union, the Allied forces supported the latter. The war ended with the ultimate defeat of Germany and occupation of several European countries by the Red Army.

The subsequent sovietisation of Central and Eastern European countries could occur solely as a result of their occupation by Red Army units. This unequivocally showed that the Soviet military was the means of carrying out the aggressive policies of the Kremlin.

Although the Kremlin propagandist rhetoric about the „love of peace” and „fight for peace” never left the front pages of the Soviet newspapers, the Soviet Army participated in dozens of military conflicts across the globe, supporting regimes sympathetic to the Soviet Union, mostly acting as aggressors together with the local forces or rebels.

Popular uprisings in the German Democratic Republic (1953), Hungary (1956) and Czechoslovakia (1968) were supressed by the Soviet Army, officially presenting their activities as fulfilling the „international duty”. The same tactic was used to explain to the Soviet people the reasons and objectives of invading Afghanistan in 1979. Officers did not have to pay taxes and they were given significant reductions in utility costs. The wages were on the same level as those of the members of the party apparatus and the KGB. During the final years of the existence of the Soviet Union, the military was sent to supress independence movements in the Soviet republics, e.g. in Tbilisi in 1989 and Vilnius in 1991.

Sources

Literature and materials:

22nd Congress of the CPSU. Verbatim report I. Tallinn, 1962.

L. Brezhnev. Report of the Central Committee of the CPSU to the 24th Congress of the CPSU, 30 March 1971. Tallinn, 1971.

K. Marx, F. Engels. Manifesto of the Communist Party. Tallinn, 1974.

J. V. Stalin. Leninismi küsimusi. Tallinn, 1952.

Д.Т. Шепилов. Советский патриотизм. Pravda, 11 August 1947.

Marc Jansen, Nikita Petrov, Stalin’s Loyal Executioner: People’s Commissar Nikolai Eznov, 1895-1940. Hoover institution press, Stanford, California, 2002, 274 p.

История сталинского Гулага. Конец 1920-х – первая половина 1950-х годов: Собрание документов в 7 томах – М. 2004.

Лубянка: ВЧК–ОГПУ–НКВД–НКГБ–МГБ–МВД–КГБ. 1917–1991. Справочник / Под. ред. акад. А.Н.Яковлева; авторы-сост.: А.И.Кокурин, Н.В.Петров. М., 2003.

Лубянка. Сталин и ВЧК–ГПУ–ОГПУ–НКВД. Архив Сталина. Документы высших органов партийной и государственной власти. Январь 1922 – декабрь 1936. Под ред. акад.

А.Н.Яковлева; сост. В.Н.Хаустов, В.П.Наумов, Н.С.Плотникова. М., 2003.

Лубянка. Сталин и Главное управление госбезопасности НКВД. Архив Сталина. 1937–1938. Под ред. акад. А.Н.Яковлева; сост. В.Н.Хаустов, В.П.Наумов, Н.С.Плотникова. М. 2004.

Лубянка. Сталин и НКВД–НКГБ–ГУКР СМЕРШ. 1939 – март 1946 / Архив Сталина. Под общ. ред. акад. А.Н.Яковлева; сост. В.Н.Хаустов, В.П.Наумов, Н.С.Плотникова. М., 2006.

Лубянка. Сталин и МГБ СССР. Март 1946 – март 1953: Документы высших органов партийной и государственной власти / Сост. В.Н.Хаустов, В.П.Наумов, Н.С.Плотникова. М., 2007.

Петров Н. Палачи: Они выполняли заказы Сталина. М., 2011. 320 с.

Петров Н.В. Первый председатель КГБ Иван Серов. М., 2005. 416 с.

Реабилитация: как это было. Документы Президиума ЦК КПСС и другие материалы. Том 1. март 1953 – февраль 1956. Сост. Артизов А.Н., Сигачев Ю.В., Хлопов В.Г., Шевчук И.Н. М., 2000.

Реабилитация: как это было. Документы Президиума ЦК КПСС и другие материалы. Том 2. февраль 1956 – начало 80-х годов. Сост. Артизов А.Н., Сигачев Ю.В., Хлопов В.Г., Шевчук И.Н. М., 2003.

Реабилитация: как это было. Документы Политбюро ЦК КПСС, стенограммы заседаний Комиссии Политбюро ЦК КПСС по дополнительному изучению материалов, связанных с репрессиями имевшими место в период 30–40-х и начала 50-х гг. и другие материалы. Том

3. Середина 80-х годов – 1991. Сост. А.Н.Артизов, А.А.Косаковский, В.П.Наумов, И.Н.Шевчук. М., 2004.

Сталинские депортации. 1928–1953 / Под. общ. ред. акад. А.Н. Яковлева; Сост. Н.Л.Поболь, П.М.Полян. М. 2005.