An unbearably discernible tragedy. Deportation

State authorities have organised deportations since antiquity in order to eliminate the danger of rebellions or to solve economic problems. However, in Stalinist Soviet Union, this form of repression acquired an industrial scale: deportations were carried out one after another and prominent administrative resources were involved in selecting and capturing the victims.

The proceedings of the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory entitled The “Priboi” Files: Articles and Documents of the March Deportation of 1949" mainly focuses on the mass deportation that affected Estonia most painfully, but was by no means the last deportation from Estonia.

The book gives a thorough overview of the Soviet regime’s criminal operation during which approximately 7550 families were deported from Estonia (altogether 20 600 – 20 700 people). The articles cover the prequel of the March Deportation and its execution, the lives of the deported in Siberia, the assessment given to the operation by the Communist Party, the liberation of the deportees as well as the public discussion and research on the event. The other half of the book consists of document publications, which are a great help to anyone researching the March Deportation.

The book helps those interested get acquainted with the deportation’s circumstances and facts, but the publication has another important value. It sheds light on the fate of surprisingly numerous people who ended up falling victim to errors made during the deportation operation. The Soviet mass deportation was repression on an industrial scale. Therefore, characteristically to Soviet circumstances, errors were inevitable, and they occurred in astonishing numbers and forms.

Although the Ministry of State Security put a lot of effort into uncovering the people to be deported (as well as their family members), many mistakes were made in the process. People were mistaken for or swapped with others. In addition, the authorities were purposefully cynical. For example, families of Red Army veterans were placed for deportation, although according to deportation’s official criteria, such cases ought not to have occurred.

As a consequence of intentional or accidental mistakes, families that sincerely had not wronged the Soviet regime were sent to Siberia, while other well-known German occupation era activists remained untouched. “Therefore, it’s no wonder that the local population misunderstood the reasons behind the deportation of specific families. Consequently, legends about local informants or compilers of deportation lists, who acted on personal enmity or interest, were easy to arise,” Andres Kahar, the author of the article “The preparation of the March Deportation”, says.

On the eve of the deportation, a so-called “active” was summoned in parishes under a made-up pretext, in order to use them as helpers in the operation. As no one knew that the deportation will follow, people who were themselves destined to be deported, arrived in parish houses, and some even had to lead the soldiers into the household of their loved ones. We can only imagine the mental burden such person had to bear and live with.

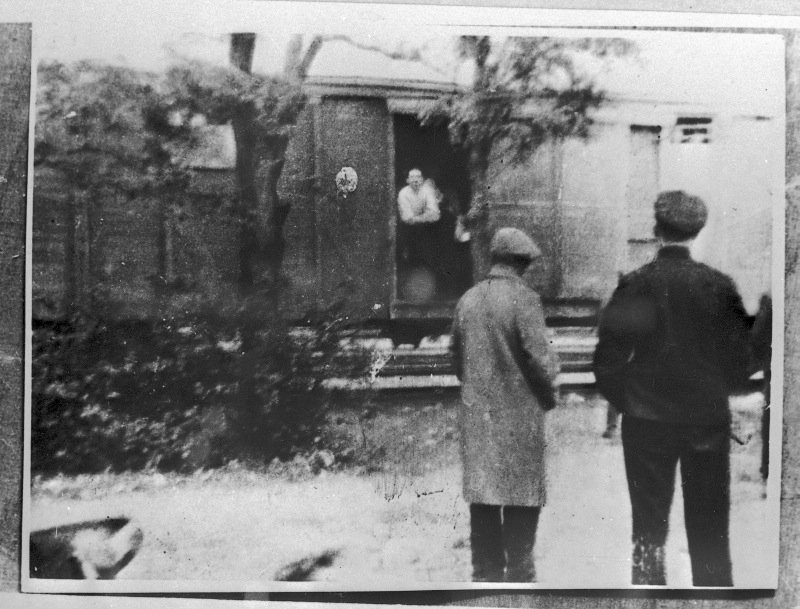

It is not often acknowledged that nearly a third (~10 000 people) of those that were meant to be deported were not arrested and sent away. Instead, people that had been placed in the so-called “reserve” list were chased into the cattle cars, in order to fill the necessary quota. These 10 000 people had to keep on living in the Stalinist Estonian SSR as outlaws: their property had been confiscated and they carried the sign of an “enemy of the people”, but were formally free and had to carry on with their life and keep on paying the kulak taxes.

Not deporting a third of the victims did not really bother Moscow, because the March Deportation filled its terrorist purpose anyway, scaring people into kolkhozes. For the local communist schemers, this proved to be useful information in the power struggle. Therefore, the leadership of the Communist Party, led by Nikolai Karotamm, who was taken down in the plenary session held in March 1950, also fell victim to the errors made during the deportation.

Confusion and mistakes continued even after Stalin’s death with regard to the liberation of the deportees, as its regulation was unclear. Those that returned to Estonia experienced the disdainful attitude of local authorities and their bootlickers, including restrictions on place of residence and other humiliations, although people’s civil rights had seemingly been officially restored.

Those that had been deported as children formed a special sub-category. Legally, they had never been personally punished or repressed; nevertheless, they had to experience various restrictions, some more veiled, some less, as an adult.

There are even more examples in the book’s articles and documents of people and groups that ended up in unsafe paradoxical and ambiguous situations due to the brutality, bureaucratic indifference and “natural” defectiveness of the deportation operation’s industrial repressive apparatus. Such examples illustrate valuable nuances of the reality at the time, they give a feel of real-life (and, as is the subject of the book, death), and the human tragedy caused by the deportation suddenly becomes unbearably discernible.