Tallinn on Fire 1944. Remembering, forgetting, commemorating

Today we commemorate not only the human victims but also the city as a whole, a living organism, which despite postwar reconstruction, will never again be the same as it was before 1944," writes historian and emeritus professor at the University of Toronto, Jüri Kivimäe.

Eighty years have passed since the tragic events we are commemorating today. Of those who survived the bombing of Tallinn in March 1944, few witnesses remain alive today. At the time, most of them were children, though the fiery war left many of them with deep traces and scars in their childhood memories. But they are indeed the last of those who can personally remember that horrific night. To be precise, only people remember; history consigns things to oblivion. And if the witnesses of the Soviet air raid on Tallinn are no more, they did tell the next generation about the horrific night.

However, we do have a fair amount of evidence from various recollections as well as historical records about what really happened. Tallinn had been embroiled in war for the third year in a row, occupied by Nazi Germany, though the front was some distance away at Narva. There had been repeated Soviet air raids on Tallinn in 1942 and 1943. At the beginning of 1944, the population of Tallinn was approximately 133,000 or even less: it was a city of the elderly, women and young children.

At that time, the air war was intensifying throughout Europe. In February 1944, the Soviet air force bombed Helsinki three times. At the beginning of March, the Americans waged two bombings of Berlin involving over 600 bombers. German cities and railway junctions were being bombed relentlessly.

The ongoing horrors of war in Estonia were marked by the evening of the 6th of March when Soviet forces waged a massive air raid on Narva, which at the time was almost empty of people; as a result the historic old city lay in ruins. Three days later, on the cloudless evening of the 9th of March, the blackout began at sunset, 20 minutes before 6 o’clock PM. There was no way to foresee the catastrophe that was about to happen. At the “Estonia” theatre, a performance of the ballet “Kratt” (The Goblin) by Eduard Tubin was scheduled for 6 o’clock that evening, and in downtown cinema theatres, German entertainment films were being shown.

So early in the evening hour, no one could suspect the onset of an air raid. But indeed, that's what happened: the air raid began at 6.15 in the evening. Lightning bombs, so-called “Christmas trees,” appeared in the sky, and air raid sirens were set off; anti-aircraft cannons opened fire on the airplanes, but then everything was dissolved in the noise of the oncoming explosions. The direction of the attack extended over Lasnamäe, Kadriorg, and Keldrimäe, and the district located opposite the “Estonia” theatre, spanning the southern sector of the Old Town, but bypassing Toompea. The main direction of the bombing turned across Pärnu Highway, into the vicinity of Luise, Väike-Ameerika and Suur-Ameerika Streets, skirting Lilleküla and Pelgulinn and continuing over the Kalamaja area back to the sea. The Soviet bombers attacked in columns in several waves; there are claims that there were fifteen-minute to half an hour intervals between waves. The first air raid lasted just under three hours. According to police reports, 240 bombers participated in the evening attack, and it's possible that approximately 2400 bombs were dropped on the city.

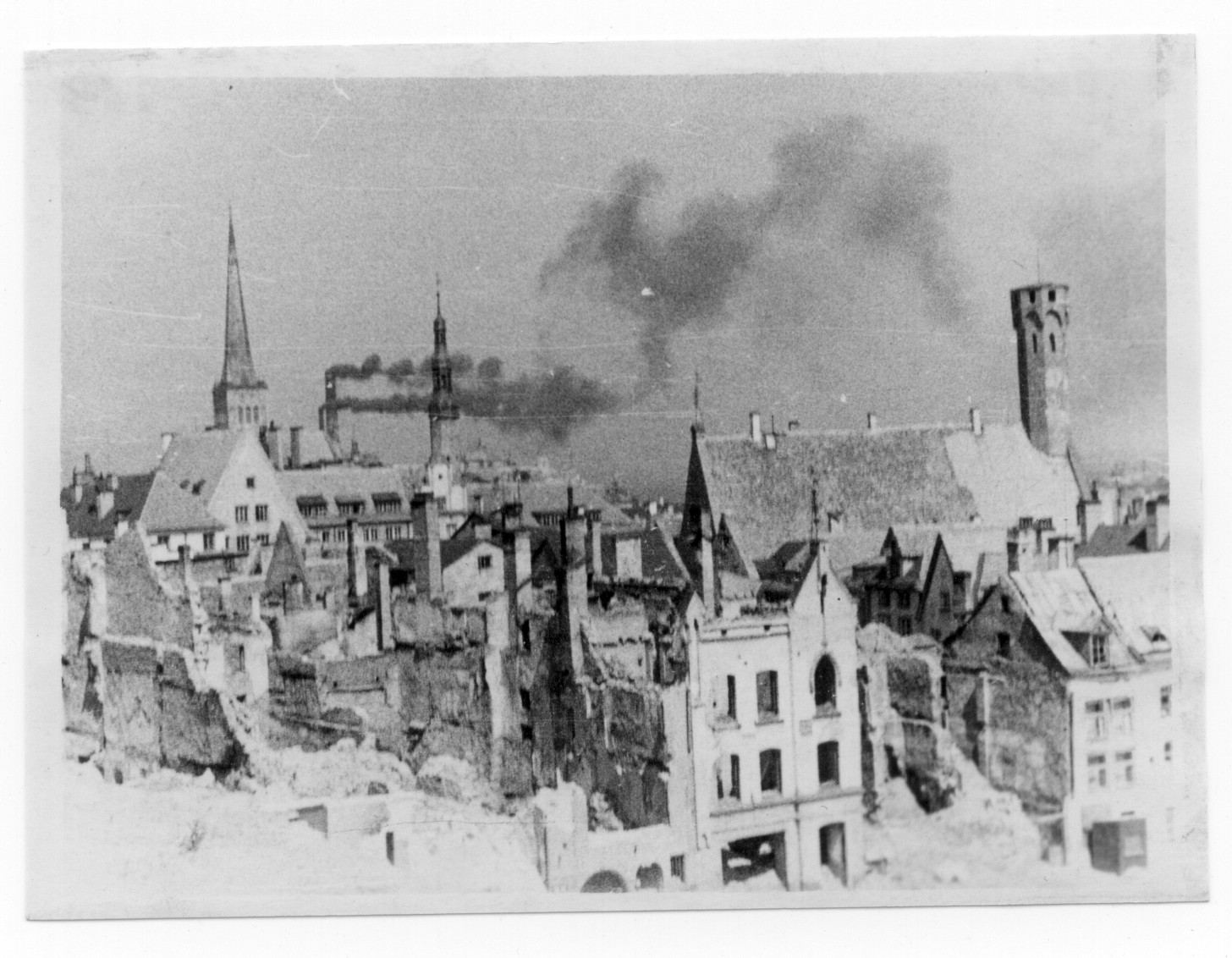

Indeed, Tallinn presented an awful picture on the evening of March 9th. Harju Street was burning, as the “Kuld Lõvi” (Golden Lion) restaurant and the cinema theatre “Amor” had received a direct hits. The “Estonia” theatre, the St. Nicholas Church, the Town Hall Tower and the Tallinn City Archives building on Rüütli Street, the Jewish Synagogue on Maakri Street, as well as many other buildings were ablaze. The fire spread very quickly, seizing whole neighborhoods in districts with wooden housing. The calm weather of that evening had turned windy due to the fire. On Harju Street, the wind speed was close to storm level. City fire departments were unable to extinguish the fires; the central city water connection had been directly hit, and because of the power outage, the water filtration pumps were disabled. Thus due to the lack of water, the fire at the “Estonia” theatre building could not be put out.

The air raid caused shock and panic among inhabitants of Tallinn; an unconscious fear deepened that the bombing would continue. Unfortunately, these fears were corroborated. Just after midnight, at one o’clock on March 10th, a new air raid began, lasting two hours. Police reports indicate that 60 airplanes took part in this second bombing of Tallinn. The rationale for the second wave of bombing of a burning city remains unclear. Survivor testimony as well as historical analysis confirm that this was a terror attack.

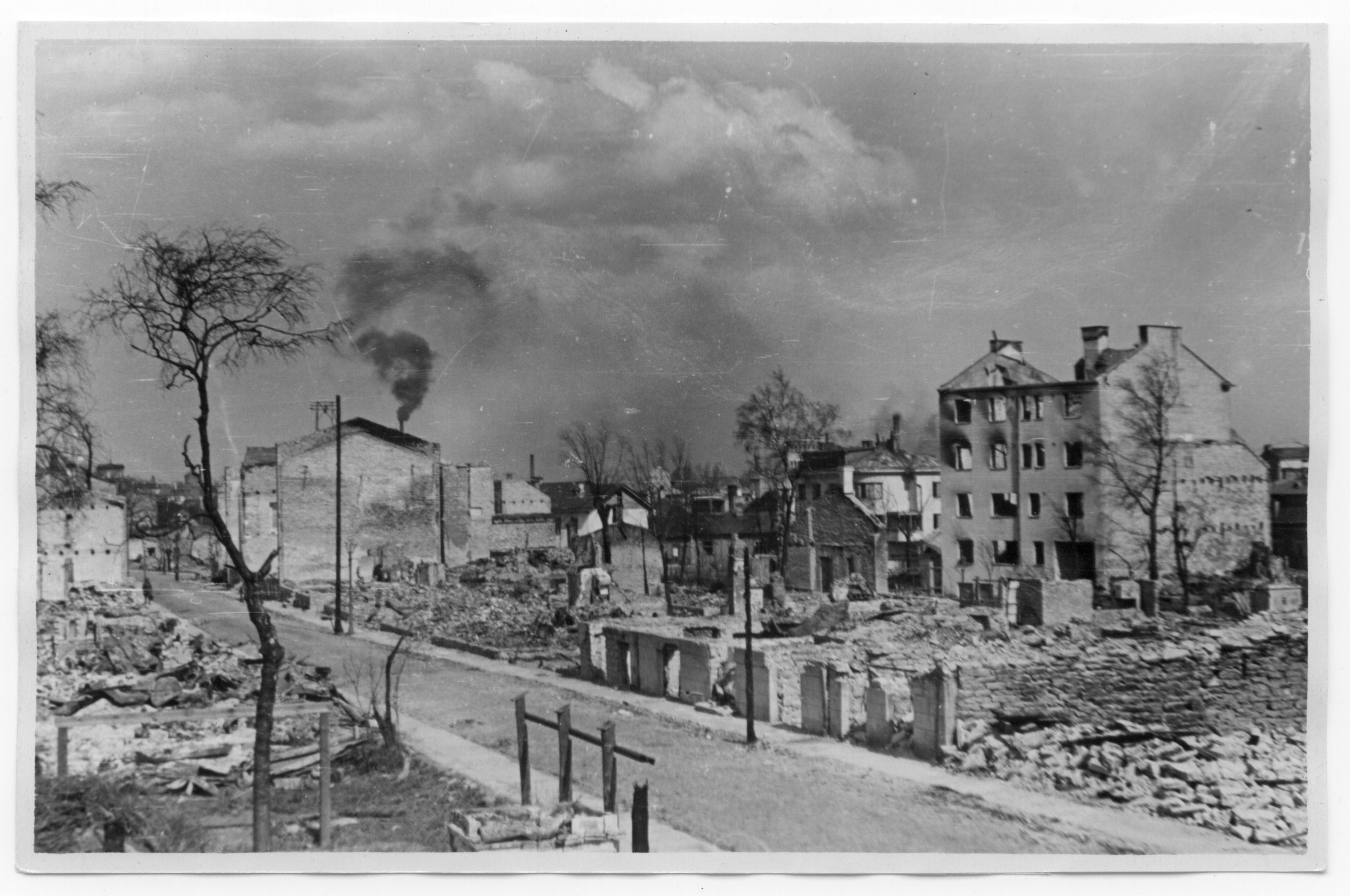

Today, we know that the human toll of the air raids was very high. According to specified sources, 558 civilians perished along with 171 soldiers and prisoners-of-war, not to forget 659 wounded; therefore, the total number of victims may have been as great as 1400. Approximately 20,000 inhabitants remained without shelter; 1418 residences were destroyed and a total of 3350 residential buildings suffered greater or lesser damage.

The historic city of Tallinn was in ruins, sharing the fate of European cities that underwent air raids with large numbers of victims, the landscapes of which were utterly transformed by the air war: Coventry and London in UK, Hamburg, Cologne, Dresden and Lübeck in Germany, Helsinki in Finland and many others.

Years have passed and the horrors of the March 1944 air raids are slowly beginning to fall into oblivion. Whether or not we want to acknowledge it, forgetting is the obverse of remembering. We can no longer conjure up the image of Harju Street in firestorm, nor the burning “Estonia” theatre, let alone the continuous flow of refugees who left Tallinn that night or during the next days. No one among us would choose to be, for example, in the St. Nicholas Church with a burning steeple that threatened to collapse at any minute. Memories only contain isolated references to the ways people might have been thinking at that time as they made their way through the ruined streets — the smell of charred, still-smoking buildings, the stench of dead animals and people who were buried under the ruins. It is humanly understandable that it was imperative to forget, to shut this out of recollections.

It was by dint of fate that the March bombing sank under the dramatic events that followed – the 1944 summer of war, the retreat of Nazi German Wehrmacht units and the great flight of many Estonians over the Baltic Sea; the chaos that prevailed in early fall 1944 and the return of the Soviet regime. While on March 13, 1944, the Soviet information agency TASS reported that their air force had heavily bombed German military trains at the Tallinn railway point as well as enemy ships in Tallinn harbor, and the fire was visible to Soviet pilots 250 km away, by the end of that same year, the Soviet side began to deny the bombing of Tallinn by Red Army pilots.

Furthermore, Soviet reports presented to the Nuremberg trials attributed the wartime bombings of Narva and Tallinn to Nazi German war crimes. In Soviet-era printed sources, there is no mention anywhere of the March bombing of Tallinn. According to Soviet history politics, such forgetting was obligatory. Indeed, in the second volume of “The History of Tallinn,” published in Estonian in 1969, there is a very brief treatment of the German occupation, and the source is silent about any air raids on Tallinn. Propaganda-based legends are durable, and even today there may be people who believe them. Besides Soviet propaganda, another version is baffling: the persistent belief that the large-scale bombing of Tallinn was carried out by the British with their own airplanes or by the Russians with the help of British instructors.

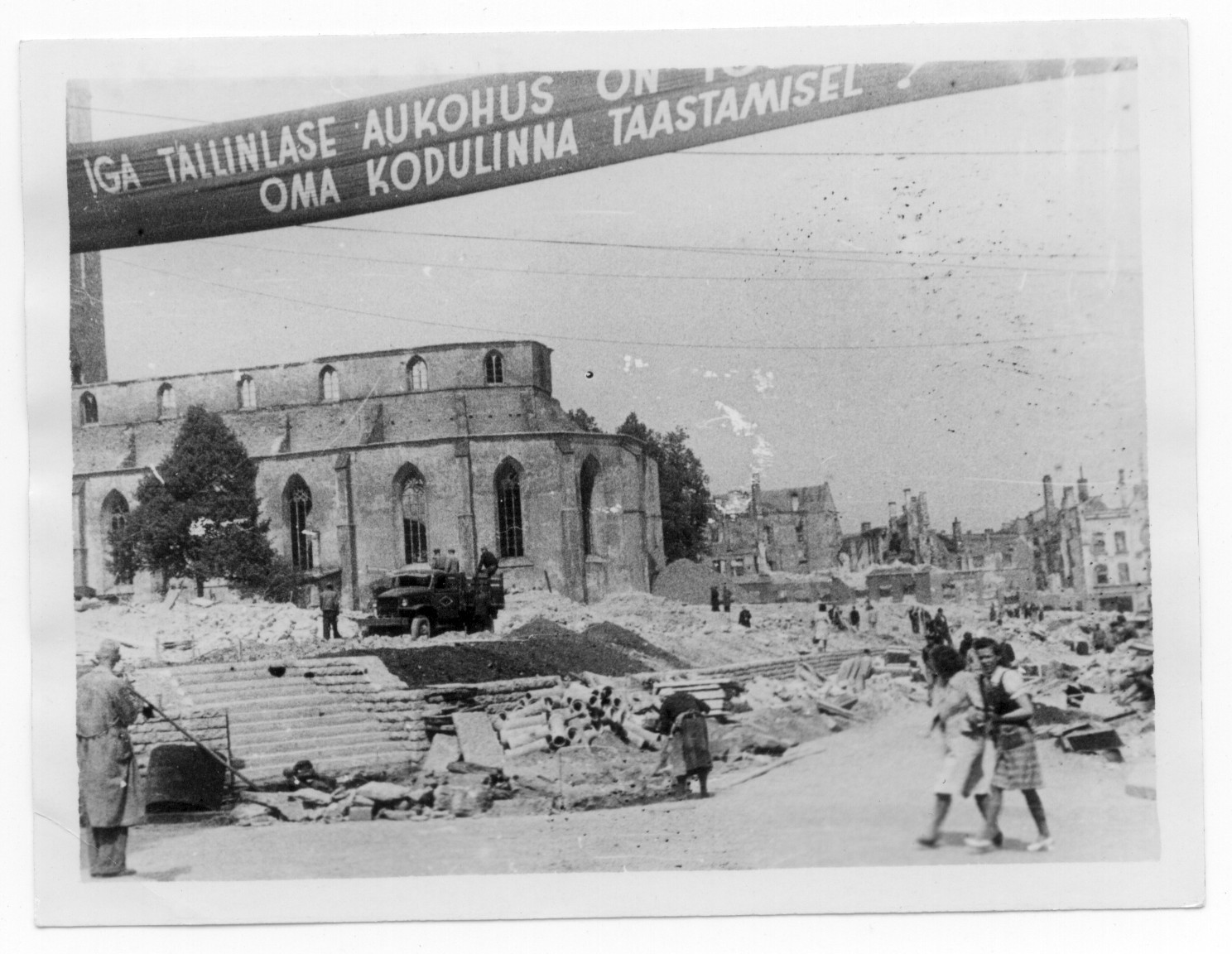

However, Estonian historical memory has maintained that in 1942–1944, bombings of Tallinn were carried out by Red Army pilots, and this is confirmed by historical facts. Indeed, the memories of those who fled into exile after the March bombings were the first testimonies to be recorded and published. In 1993 when preparations were being made by the Tallinn City Archives to compile a collection of documents and memoirs about the March bombings, we were faced with serious difficulties both with respect to choosing archival documents and making selections among already effaced memories.

Today, we find ourselves in the era of commemorating these horrors of war. We must admit that such activities can only be selective. It is symbolic that our commemorations are connected to St Nicholas Church, which suffered greatly, and the nearby site of commemoration on Harju Street, which was an epicenter of raging fires that night. We do not only commemorate human victims, but the city as a whole, a living organism, which despite postwar reconstruction will never again be the city it was before 1944.

Such a commemoration of the historic city of Tallinn is not singular. Almost 450 years ago, during the Livonian War, Tallinn survived six months of siege by Muscovite forces. At the lifting of the siege on 26 March 1571, the Tallinn City Council decided to declare the day a holiday for all time. For over 100 years, bells rang out from Tallinn’s churches, and people flocked to hear pastors singing a special prayer at the altar, declaring that a time for celebration had come once again. Later, this day of remembrance fell into oblivion, though efforts were made to reinstate it in 1926.

Juxtaposing our day of remembrance with this other one, centuries earlier, speaks of the inexplicable miracle of Tallinn’s past: throughout its entire 800-year history, it has never been conquered militarily. This bears an important message for today as well. Hostility and war destroy, but peace nourishes the land.

Further readings

Götz Bergander, Dresden im Luftkrieg. Vorgeschichte, Zerstörung, Folgen. Weimar, Köln, Wien: Böhlau Verlag, 1994.

Toomas Hiio, Meelis Maripuu, Indrek Paavle, (toim.) (2006). Estonia 1940–1945: reports of the Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity. Inimsusevastate Kuritegude Uurimise Eesti Sihtasutus: Tallinn, 2006.

Toomas Hiio, Tallinna pommitamine 1944. a. märtsis. Estonica Entsüklopeedia Eestist, 2009. http://www.estonica.org/et/Tallinna_pommitamine_1944_a_märtsis/

Paul Johansen, 16./26. märtsi tähtsusest Tallinna ajaloos. – Paul Johansen, Kaugete aegade sära. Tartu: Ilmamaa, 2005, 146–151.

Jaak Juske, Tallinna märtsipommitamine 1944. [Tallinn] 2014.

Jüri Kivimäe, Lea Kõiv (koostajad), Tallinn tules. Dokumente ja materjale Tallinna pommitamisest 9./10. märtsil 1944. (Tallinna Linnaarhiivi toimetised nr. 2). Tallinn, 1997.

Jüri Kivimäe, Märtsipommitamine Tallinnas anno 1944. – Tallinn tules, 15–30.

Taavet Liias, Tallinna õhutõrje 1944. aasta märtsipommitamise ajal. – Akadeemia 2010, No. 3, 417–435.

Norman Longmate, Air raid: The bombing of Coventry, 1940. London: D. McKay, 1978.

Keith Lowe, Inferno: The Fiery Destruction of Hamburg 1943. New York: Scribner, 2007.

Sinclair McKay, Dresden: leegid ja pimedus. Dresdeni pommitamine 1945. Tallinn: Tänapäev, 2020.

Kadri-Ann Mägi, 1944. aasta märtsipommitamised ja nende kajastamine ajalehtedes Eesti Sõna ja Postimees. (Tartu Ülikool, BA Thesis). Tartu, 2018.

Jukka L. Mäkelä, Helsinki liekeissä. Suurpommmitukset helmikuussa 1944. Helsinki: WSOY, 1967.

Hanno Ojalo, Tallinn põleb! 9. märts 1944. Tallinn: Ammukaar, 2018.

Reigo Rosenthal, Tallinna 1944. aasta märtsipommitamine Punaarmee kaugtegevuslennuväe dokumentide valguses. – Tuna 2022, No. 4, 77–92.

Ian Thomson, Pommid Tallinna taevas. – Looming 2021, No. 3, 363–374.