A Rare Diary: Destiny of An Estonian German Who Was Deported in 1945

The majority of the Baltic Germans left Estonia for Germany in 1939–1941 on the basis of agreements concluded between Germany and the Soviet Union. However, some remained in Estonia. One of them was Georg Heitmann who was deported to Russia. He was seventy at the time. The article was first published in the Saturday supplement of the Estonian daily Päevaleht.

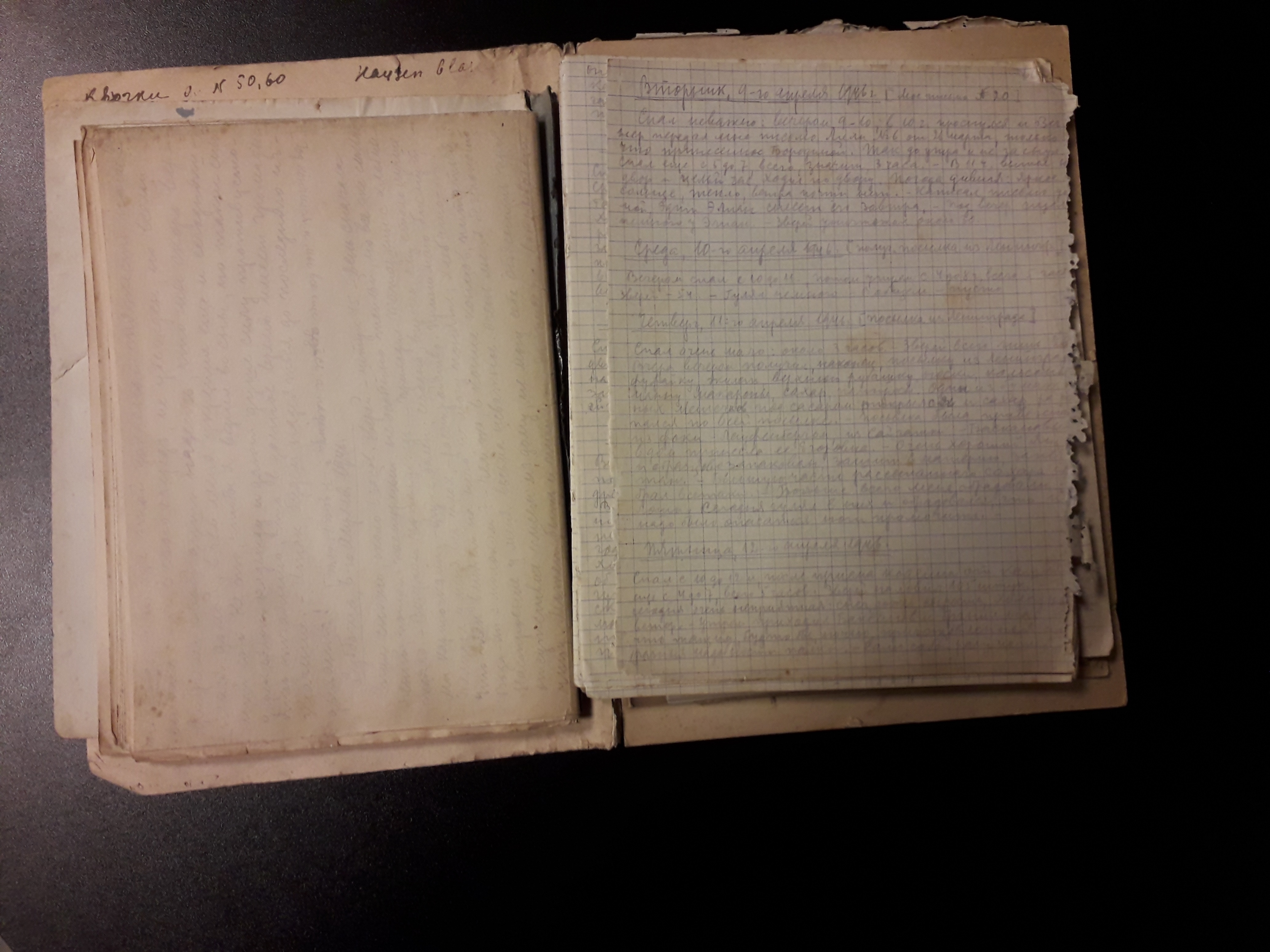

It is from the diary of Heitmann that we learned the details about his deportation. The author’s granddaughter Inna-Maia Paiken gave the diary to the International Museum for the Victims of Communism, that the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory is creating in the Patarei Prison in Tallinn. We encourage others to donate to the museum (opens in 2026) historical items and materials, including photos and documents about repressions and persecution by, resistance to and flight from the Soviets, as well as other similar experiences.

Inna-Maia first approached the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory with the request to specify the data about her relatives in the database of Estonia’s Victims of Communism Memorial (www.memoriaal.ee). As we talked, Paiken mentioned a diary that she had found among her mother’s belongings.

According to Senior Researcher of the Institute Olev Liivik, Inna-Maia had firmly decided to donate the diary, so as to ensure its safekeeping and preservation. „The story about the deportation of an Estonian German enshrined in a diary is such a rarity that we decided to digitise it immediately,“ Liivik said. The diary was written in Russian, so Inna-Maia first translated it into Estonian. „Talks with Inna-Maia helped me better understand her grandfather and his way of life. Without Inna-Maia’s help it would have been very difficult to get a grasp of the story,“ the historian added.

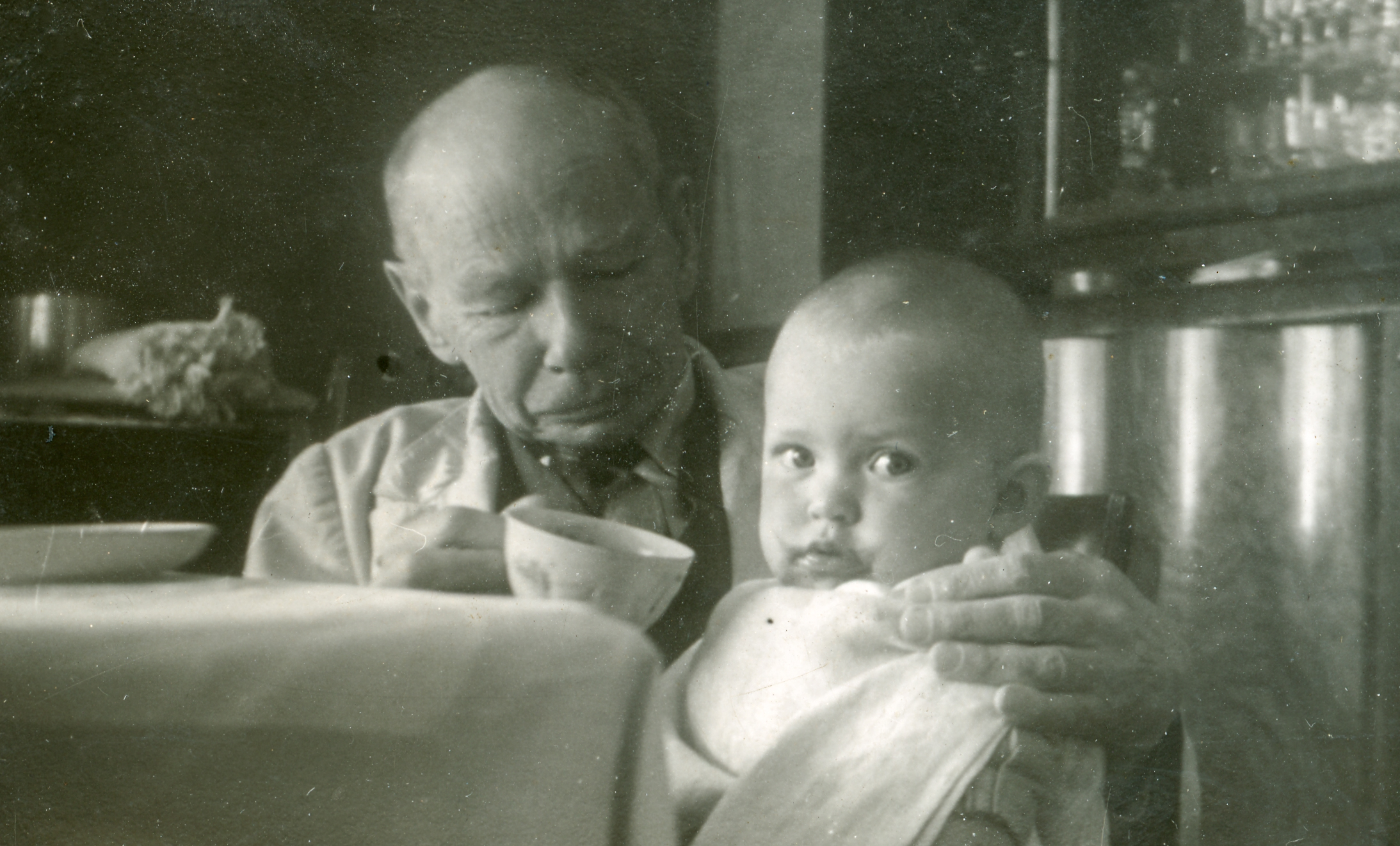

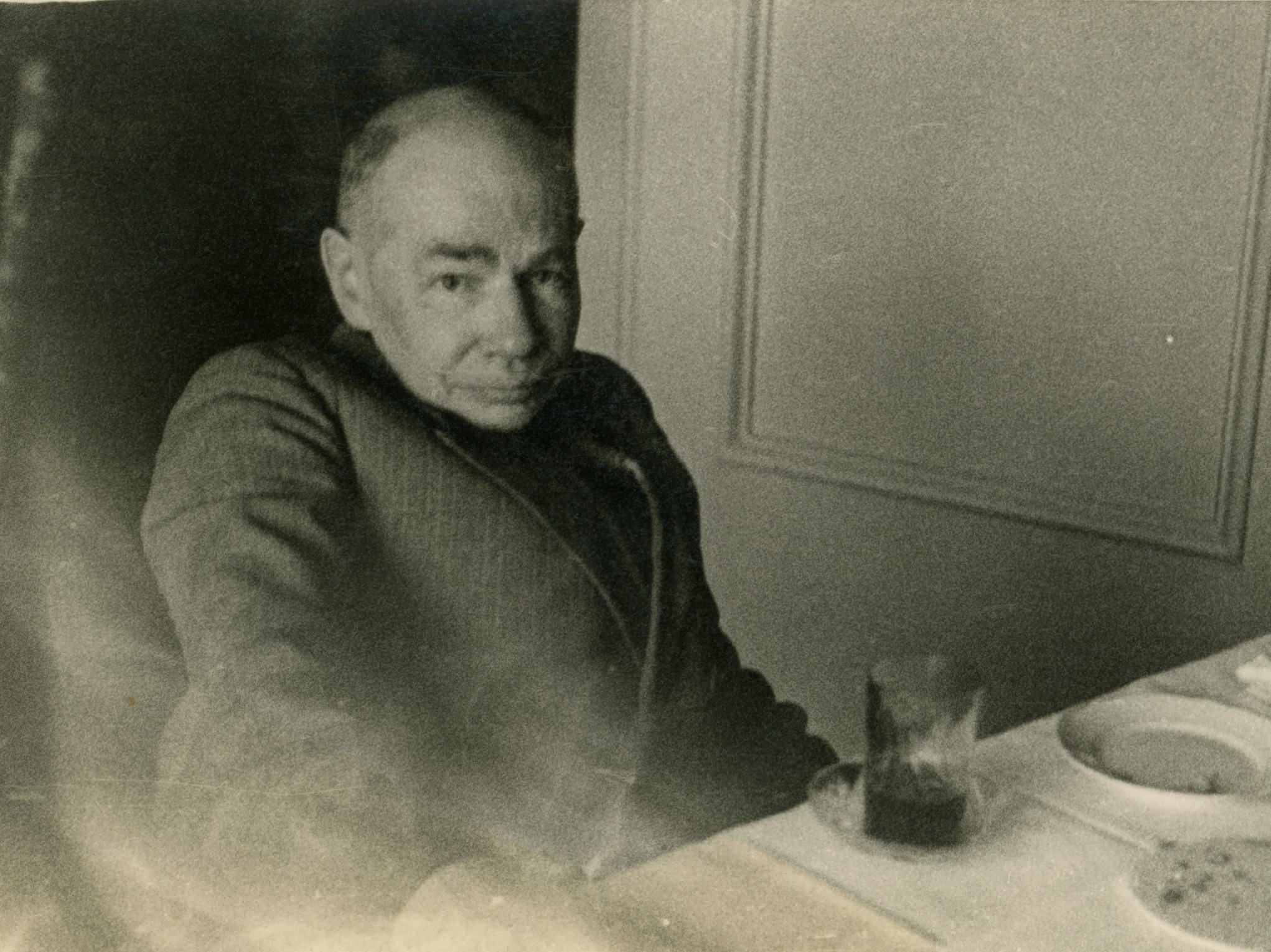

Georg Heitmann was a Baltic German who worked as head accountant of the Wool Factory in Kärdla, the Island of Hiiumaa. Earlier, he had also held the position of accountant in Saint Petersburg, where he acquired an excellent command of the Russian language.

Right after occupation, the Soviet authorities started repressions against the locals, both Estonians and the few Germans remaining in Estonia. In light of the German-Soviet conflict any German nationals were automatically deemed dangerous, and the attitude persisted after the end of the war as well.

In 1945, when Georg Heitmann was deported to Russia, he was an ailing 70-year-old man. However, he escaped two years later and returned to Estonia. In 1949 he was arrested and sent to a forced-labour camp.

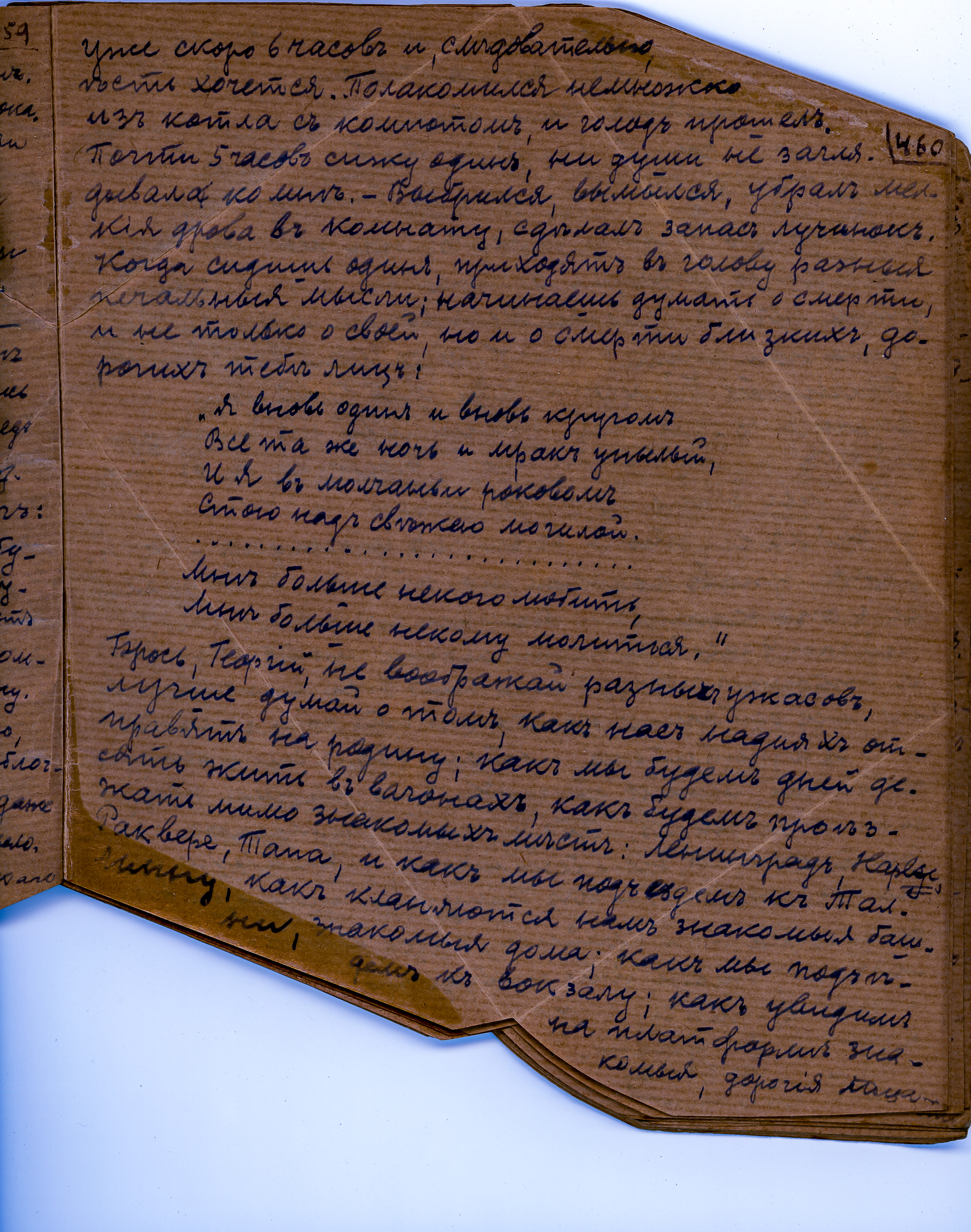

His diary contains regular entries from 1945 to 1947. He tells mostly about his daily life in Russia. There is a lot of mention about food, how to obtain food, about hunger and relations between the deportees, but also about rumours – all of which could be a subject of an independent research paper.

This is what Heitmann wrote on 2 March 1946, „A third day without bread – what are our leaders thinking about! No fats either; this is why I had potatoes with sauce made of egg powder, instead of morning porridge. Selling of things has come to a complete stop, no one wants to buy anything, i.e. to exchange stuff. There is no money either, I do not know, what is going to happen – must starve.“

The entry of 5 April is more optimistic, „Again there is a lot of talk and heated arguments about our returning home or staying for ever in Russia. Even if the proponents of „our staying for ever“ are so convinced in defending their position, we can still hear the hope behind their words, that we will, eventually, really, return home in the near future! Yet I am sure that without hope, be it apparent or secret, none of us would be able to tolerate the unbearable burden of our being.“

Most of the entries were made in the two villages, Chernushka and Melnichnaya in the Perm (Molotov) oblast, in Russia, where he lived as a „special settler“. He stopped keeping the diary after returning to Estonia on 23 October 1947.

The diary was written on any kind of paper that could be found – squared exercise books, single sheets of paper of varying sizes and even disassembled envelopes. Given that Heitmann considered his writing important, he always took care to have a sufficient supply of paper.

On 4 December 1946, he has written the following, „I notice to my dismay that I am running out of paper, with only one page left! I haven’t got a single piece of paper, apart from the small notebook, which is reserved for the letter I started to write to Lilja [his wife Jelizaveta] yesterday. I have to go begging, and not for bread, not for money, but paper! It is as bad as that now! I first turned to the landlord; I just explained to him that I desperately needed some paper and he immediately went and tore out four pages from an old exercise book. How very touching!“

According to Olev Liivik the diary is truly exceptional, since very little is known to the historians about the deportation of Germans in 1945 and what there is, comes from the perspective of the occupational forces. There are some lists of people, documents about conducting the operations, letters of appeal and complaints, and case-files of the deportees who later sought rehabilitation or special settlers who were arrested because they had escaped from Russia. Nothing from the perspective of victims was known to exist and that makes the diary extremely valuable.

Heitmann wrote a lot about his surroundings, as well as his feelings and longings, about suffering and death. This is a very depressing entry, dated 2 March 1947, „I have excruciating pain in my chest, my bones ache, especially on the right side; coughing is really painful, lying down is difficult and I cannot stand up without a cane. This is something new I’ve got: the end is near! If only I could get home before this happens, don’t want to die here. I would dearly wish to see my loved ones just once before I die!“

Such entries are touching, but also difficult to read. However, such writings like Heitmann’s diary could be made compulsory reading at school. That would help us understand what a good life we have today.

Heitmann was sent to the force-labour camp in 1949 and finally released in the summer of 1955. He was of very poor health at the time and therefore the camp doctor wrote to Georg’s family to come and get him, for he was so ill that he could not travel back to Estonia on his own. Sadly, Georg never made it home, but passed away in the same summer of 1955 in a nursing home in the country he was exiled by force.

What happens next?

The diary will be preserved in accordance with the requirements for preserving museum objects. Digitised extracts of the diary can be displayed in the International Museum for the Victims of Communism to be opened in the Patarei Prison. The almost 80-year-old paper has become brittle and fragile and has to be kept under special conditions as regards temperature, humidity, etc, to avoid it deteriorating even further. However, there are plans to publish the diary and thus make it available to all readers.

The Estonian Institute of Historical Memory invites people to share their (family) stories, donate materials to the museum (objects, photos, diaries, documents etc), which are related to the Soviet occupation forces, the red terror, persecution of innocent people, resistance activities etc. If you want to donate anything to the future museum, please contact the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory by e-mail: info@mnemosyne.ee or telephone +372 664 5039.

In 2026 the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory will open the International Museum for the Victims of Communism in the former Patarei Prison (https://patareiprison.org/). The museum will display materials about crimes against humanity and human rights violations committed by communist regimes in Estonia and elsewhere in the world. In a way it is an extension of Estonia’s Victims of Communism Memorial. The Estonian Institute of Historical Memory created the list of the victims whose names are enshrined in the Memorial Wall and continues adding names to the electronic database.

Check the data about your relatives in the database of Estonia’s Victims of Communism Memorial www.memoriaal.ee. Please send any corrections and new information about the people who suffered repressions by e-mail memoriaal@mnemosyne.ee or call us at +372 648 4962.