The Pact that started World War II

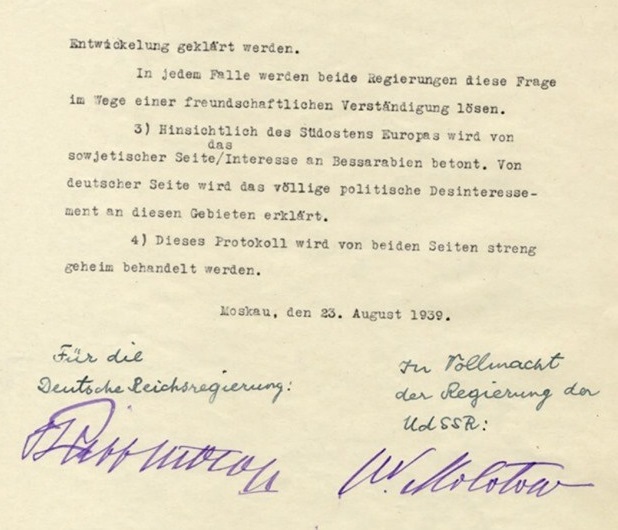

On August 23, 1939, Hitler’s Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop and Stalin's People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov signed the non-aggression pact between Germany and the Soviet Union in Moscow. Germany and the Soviet Union promised to maintain neutrality in the event of military conflicts with a third party and to refrain from attacking each other. The two regimes also secured their respective spheres of influence in Eastern Europe and described those spheres in a secret supplementary protocol, a document whose very existence the Soviet Union denied for decades. The treaty, known in Germany as the Hitler-Stalin Pact (though more commonly referred to as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact), laid the foundation for the outbreak of World War II in Europe.

Ribbentrop Goes to Stalin

On August 23, 1939, the German Foreign Minister’s plane landed in Moscow. Joachim von Ribbentrop had reluctantly interrupted his summer vacation in Salzburg for the signing of a treaty, which he thought was already a done deal. The talks between Britain, France, and the Soviet Union on a potential triple alliance had just failed. The big threat had just been avoided; everything else, in Ribbentrop’s view, paled in significance.

Yet Stalin did not think the matter resolved. He demanded that Ribbentrop goes to Moscow so that, as Hitler informed his minister, “the essentials of the additional protocol desired by the Government of the USSR ... could be finalized as soon as possible.” After seven hours of intense negotiations, the parties drew up a secret supplementary protocol. In it, Germany and the Soviet Union agreed on the partition of Poland and Eastern Europe, including Finland. Four hours later, Ribbentrop and Molotov signed a nonaggression pact between Germany and the USSR. With this, the road to World War II in Europe was opened.

A few days later, on September 1, the German Wehrmacht entered Poland, and on September 17 the Red Army approached from the east. For the first twenty-two months of World War II, the Third Reich and the Soviet Union acted as allies and divided up the European continent between themselves.

When, almost two years later, on June 22, 1941, the pact was violated, the territory that Hitler was adding to his realm had increased by 800,000 square kilometers, while Stalin had expanded his empire to the west and southeast by 422,000 square kilometers. Contrary to Nazi propaganda claims and the words of Ribbentrop, who said he felt in Moscow “as if among Party comrades,” Hitler and Stalin were never real friends.

Negotiated with mutual distrust and suspicion, the Hitler-Stalin Pact pursued explicit geopolitical interests, which for Hitler to a lesser extent, for Stalin always, prevailed over ideological motives. These interests in territorial expansion were enshrined in the notorious supplementary protocol. Until the Gorbachev reforms of the late 1980s, the Soviet Union denied the existence of the protocol.

The Partition of Poland

The partition of Poland secured by the secret supplementary protocol was Germany’s and the USSR’s first goal. Despite their stated commitments, neither Britain nor France in the fall of 1939 rushed to help Poland, a country that Molotov had cynically called “the ugly brainchild of the Versailles Treaty.” Hitler and Stalin established a regime of brutal violence and terror on the occupied territories.

The Germans turned what they now called the General Governorate into a “discharge tank” to which thousands of deported Jews and Poles flocked. Here, in the Governorate, the Holocaust began, the mass murder of European Jews. Stalin, in his turn, used ruthless methods to Sovietize the Soviet-occupied areas. Western Belarus and Western Ukraine were now parts of his empire, the Baltic States were to follow in June 1940.

Both dictatorial regimes committed heinous war crimes and massacres. In the spring, the German invaders organized the so-called Extraordinary Operation of Pacification (AB-Aktion), during which thousands of real and imaginary participants in the Polish resistance were captured and murdered. Around the same time, the NKVD units shot more than 20,000 Polish officers during the Katyn mass executions.

Both dictatorial regimes committed heinous war crimes and massacres. In the spring, the German invaders organized the so-called Extraordinary Operation of Pacification (AB-Aktion), during which thousands of real and imaginary participants in the Polish resistance were captured and murdered. Around the same time, the NKVD units shot more than 20,000 Polish officers during the Katyn mass executions.

Among the forgotten pages in the history of the Hitler-Stalin Pact is the fact that the perpetrators of those campaigns of violence acted not only independently of each other but also coordinated their actions in some areas. SS servicemen and high-ranking NKVD officers met more than once and exchanged visits on the occupied territories. For example, in December 1939, they discussed actions to crack down on the Polish resistance and coordinated large-scale resettlement operations. In 1940 the German-Soviet Refugee Commission was set up for the purpose of curbing refugee flows.

Turning Points

The catastrophic consequences of the Hitler-Stalin Pact were not limited to Poland. At the highest point of the pact’s existence, in the spring of 1940, Hitler launched his Blitzkrieg campaigns across Western Europe.

With the Germans' entry into Paris and the fall of France in June 1940, the Nazi expansion in Western Europe reached its climax. It would not have been possible without the Hitler-Stalin Pact.

Large-scale supplies from the Soviet Union provided the German military machinery with raw materials, such as oil and iron. In return, Germany, based on an economic agreement reached with the USSR in February, sent eastward factory and industrial equipment. With the Germans' entry into Paris and the fall of France in June 1940, the Nazi expansion in Western Europe reached its climax. It would not have been possible without the Hitler-Stalin Pact.

Germany’s military success, achieved with no visible effort, marked a turn in the history of the German-Soviet alliance. Stalin watched Hitler with increasing mistrust and dismay. To secure a share of the “spoils,” he occupied and annexed the Baltic countries of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, which had barely retained any sovereignty since 1939. “They had nowhere to go,” Molotov said decades later. “One had to protect oneself. When we laid out our demands … one’s action has to be timely or it will be too late.… They vacillated back and forth, ... hesitated and finally made up their mind. We needed the Baltics.”

When the Soviet Union then staked its claims to Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina, the union cracked at every seam. Germany was interested in those Romanian regions too. Hitler reckoned on Romania’s oil fields and agricultural resources in his designs for southeastern Europe. Stalin won Bessarabia for himself, but after that, no assurances of friendship could fix the cracks in the Soviet-German alliance.

Since the early fall of 1940, both powers were looking for new partners. Stalin received Britain’s ambassador-at-large in Moscow. Hitler, on September 27, signed the Tripartite Pact between the German Reich, Italy, and Japan, thus creating the Berlin-Rome-Tokyo axis.

Molotov Goes to Hitler

The November 1940 visit of the Soviet People’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs to the German capital is usually seen as the last attempt to breathe life into the Hitler-Stalin Pact. At the same time, Hitler had already decided on a war against the USSR. The offensive was being prepared, and the army’s top brass was in the know. During the summer of 1940 military units were transferred eastward and to Finland, causing much concern in Moscow.

In the meantime, Hitler worked to set his eastern ally at loggerheads with Britain over Asia, thereby creating potential conditions for a two-front war. Hitler suggested that Stalin take India as compensation for leaving Finland and southeastern Europe to Germany, a move that Molotov deciphered easily.

Although Soviet claims on Finland were fixed in the secret supplementary protocol and recognized by the Germans, Stalin’s insistence on keeping Finland for himself irritated Hitler and reinforced his anti-Bolshevik sentiments, which he never gave up. With his sense of superiority toward an ideological adversary, Hitler would never have treated the USSR as an equal, seeing it only as an inferior partner. On December 18, 1940, Hitler dictated Directive No. 21, ordering an attack on the Soviet Union. According to the directive, the Wehrmacht was to enter Soviet territory from mid- to late July 1941.

The End of the Pact

The history of the Hitler-Stalin Pact ends on June 22, 1941. Years later, at the height of the Cold War, Stalin yearned deeply for the lost treaty. “Together with the Germans we would be invincible!” Stalin’s daughter Svetlana remembered her father exclaiming. Hitler was dead set on expelling Stalin from Europe; he wanted a crusade against Bolshevism.

The allies turned into sworn enemies and could now base their mutual hatred on long-standing ideological disagreements. Stalin would prefer to do without this war, though he did not have any principled objection to territorial conquests. But Hitler deliberately sought war, a war that, in May 1945 ended in the Third Reich’s defeat.

Uncomfortable memories

World War II during its first twenty-two months was a coordinated effort of Nazi Germany and the USSR. Despite its tremendous historical significance, the German-Soviet alliance is often seen as a prelude, an opening overture to the war proper, which, according to many historical accounts, unfolded only with the start of the fierce struggle between Hitler’s Reich and Stalin’s USSR.

An ultimate battle between National Socialism and Stalinism was to give meaning to all the violence of the century of the ideologies. The global contradictions of the first half of the twentieth century reached their climax in the military confrontation between Hitler and Stalin. That struggle became a safe memory zone both for contemporaries and for later generations. The history of the Hitler-Stalin Pact, on the other hand, caused and continues to cause a lot of tangible discomfort.

The significance of the Hitler-Stalin Pact for the entire history of World War II remains understated. Seen only as a tactical move that allowed Hitler to attack Poland while changing nothing in his intention to destroy the USSR, the pact did not attract much attention in the context of the Third Reich’s history. The Soviet narrative treated the alliance as Stalin’s attempt to delay the supposedly inevitable war.

The significance of the Hitler-Stalin Pact for the entire history of World War II remains understated. Seen only as a tactical move that allowed Hitler to attack Poland while changing nothing in his intention to destroy the USSR, the pact did not attract much attention in the context of the Third Reich’s history. The Soviet narrative treated the alliance as Stalin’s attempt to delay the supposedly inevitable war.

Stalin himself circulated this interpretation in 1941. A reading that became popular in the 1990s shifted emphasis to the geopolitical partition of Eastern Europe as written down in the secret supplementary protocol. The debate over the memory of this event was of great importance to the newly independent Eastern European states that had just left the Soviet empire.

At that time, the attitude toward the pact defined the entire debate surrounding Europe’s common historical memory. The demand for equal recognition of the victims of Stalinist and Nazi terror was sometimes mistakenly seen as an attempt to deny the singularity of the Holocaust. In fact, the debate was not about downplaying the importance of the Holocaust. It was a matter of critically rethinking a Western-centered understanding of European history and a prod to remind the world of the overlooked tragedy of twentieth-century Eastern Europe.

That the voices vehemently raised at the time strengthened the impression that the Hitler-Stalin Pact was primarily an Eastern European affair is one of the results of the historical work of the post–Cold War decades. Even the introduction of August 23 as the European Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Stalinism and Nazism has not changed much in that respect.

Prof. Dr. Claudia Weber is a historian and professor of European contemporary history at the Faculty of Cultural Studies at the Viadrina European University in Frankfurt (Oder). Her main research interests are in particular the history of violence and dictatorship in the 20th century, the cultural history of the Cold War, as well as historical processes of Europeanization and the history of European concepts. Notable work of hers includes a study of the massacres perpetrated by the Soviet Secret Service in Katyń (2015), and in her recently published book, titled “The Pact. Stalin, Hitler and the History of the Criminal Alliance” (2019), in which she gives a detailed account of how, between 1939 and 1941, the Third Reich and the Soviet Union acted as allies and divided up the European continent between themselves.

Literature:

Haffner, Sebastian, Der Teufelspakt. Fünfzig Jahre deutsch-russische Beziehungen, Zürich 2002.

Kaminsky, Anna/Müller, Dietmar/Troebst, Stefan (Hg.), Der Hitler-Stalin-Pakt 1939 in den

Erinnerungskulturen der Europäer, Göttingen 2011.

Snyder, Timothy, Bloodlands. Europe between Hitler and Stalin, New York 2010 (dt. Ausgabe München 2011)

Weber, Claudia, Der Pakt. Stalin, Hitler und die Geschichte einer mörderischen Allianz, München 2019.

Zarusky, Jürgen, „Hitler bedeutet Krieg“. Der deutsche Weg zum Hitler-Stalin-Pakt. In: Osteuropa 7-8/2009, S. 97-114.