OVERVIEW: Soviet "Liberators" in 1944-1945: Civilians fell victim to mass violence and robberies (historical document added)

The arrival of the Red Army was not greeted with flowers. Civilians fell victim to violence and robberies by soldiers as well as officers. A historical overview on the Red Army terror and Soviet "Liberator-myth" in Estonia 1944-1945 by Dr Peeter Kaasik, senior researcher at the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory.

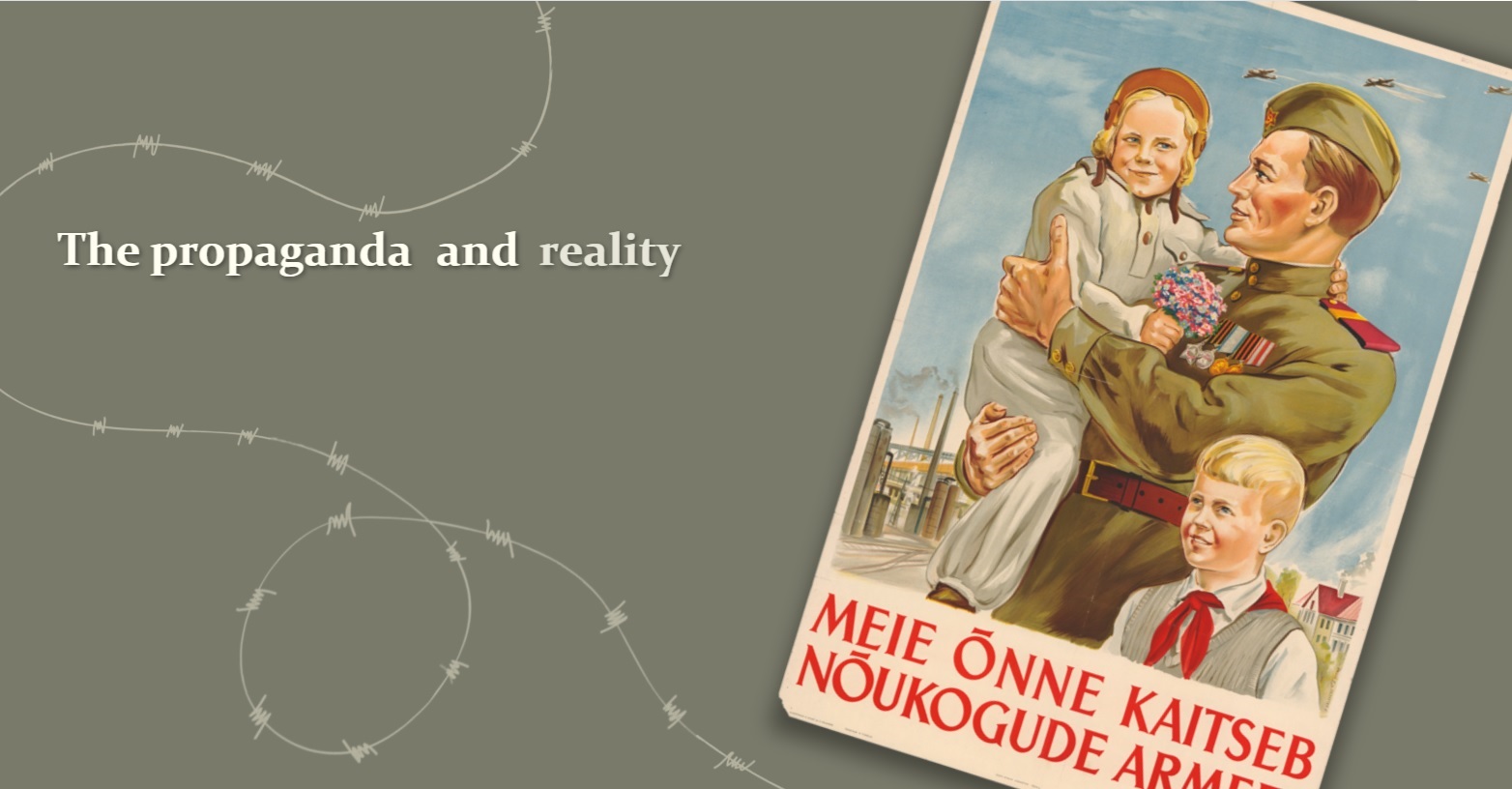

With the approaching holidays in early May it is worth remembering that the arrival of the Red Army in 1944 was not received with flowers and song anywhere in Estonia, contrary to the image cultivated by Soviet propaganda. It was clear to the majority of the population that a new occupying regime had arrived.

For the local communists, problems doubled due to the unlawfulness of the troops. They had to put a stop to the lootings while explaining to the people that a “liberator” had arrived. Already in 1944, ideologically unacceptable comparisons between the activities of the “liberator” and the German occupying regime had become widespread in reports. This indicates that Estonians had gotten out of the frying pan and into the fire.

‘The disaster that befell this area with the entry of the Soviet forces has no parallel in modern European experience. There were considerable sections of it where, to judge by all existing evidence, scarcely a man, woman or child of the indigenous population was left alive after the initial passage of the Soviet forces. The Russians swept the native population clean in a manner that had no parallel since the days of the Asiatic hordes.’[1]

This is how U.S. diplomat George Kennan described Soviet army’s advancement in 1944 and 1945 in Eastern Europe. In those days, conquests were called different names, but in later years it gradually transformed to the “liberation of Europe from the yoke of Nazis” in Soviet propaganda.

In Second World War’s Eastern front where Germany and USSR clashed, neither side recognised the 1907 Hague Convention (IV) on the Laws and Customs of War on Land. Consequently, civilians caught up in the war’s path were not protected by any binding agreement between the opposing sides.

The hostility towards German occupiers that had been publicly cultivated in the Red Army for several years, and against whom no method was deemed inappropriate, manifested itself expressly in conquered areas.

Violence against civilians amid invasions has long historical traditions. This was enhanced by the Red Army’s tactic that disregarded human lives. The soldier had to make the most of each day as any day might have been the last. In a war situation, violence against civilians had become the unofficial pattern of behaviour.

Browse an interactive exhibition with documents and posters on Red Army terror in reoccupied Estonia in 1944-1945, set against the backdrop of the Soviet Liberator-myth HERE.

The Red Army had developed a certain understanding of the enemy that justified spoils of war. As a result, they did not consider looting a war crime or even deplorable behaviour; instead, it was seen as revenge. This was the prevailing view, and not only among common soldiers.

Officers and generals at the highest level participated in the lootings, directly or indirectly. The latter, lead by marshal Georgy Zhukov, proved to be especially zealous in gathering the spoils of war[2], as they had much better means to do so, compared to a common Red Army soldier who carried out armed robberies to obtain civilians’ watches and chicken eggs.

As a result, the attempt to fight against the depredation proved to be futile. The Red Army, acting on a dog-eat-dog principle, was not punished. It was long after the war had ended that the situation was finally gotten under control.

A wave of lootings, robberies, murders and rapes that accompanied the conquests mainly hit areas inhabited by the Germans. However, other regions and countries that were considered “hostile” and “foreign” were not left untouched either. The enemy borders were quite vague, and paradoxically the looting hit areas that the USSR considered its “own”, among others Estonia, that was occupied and annexed by the Red Army for the second time in 1944.

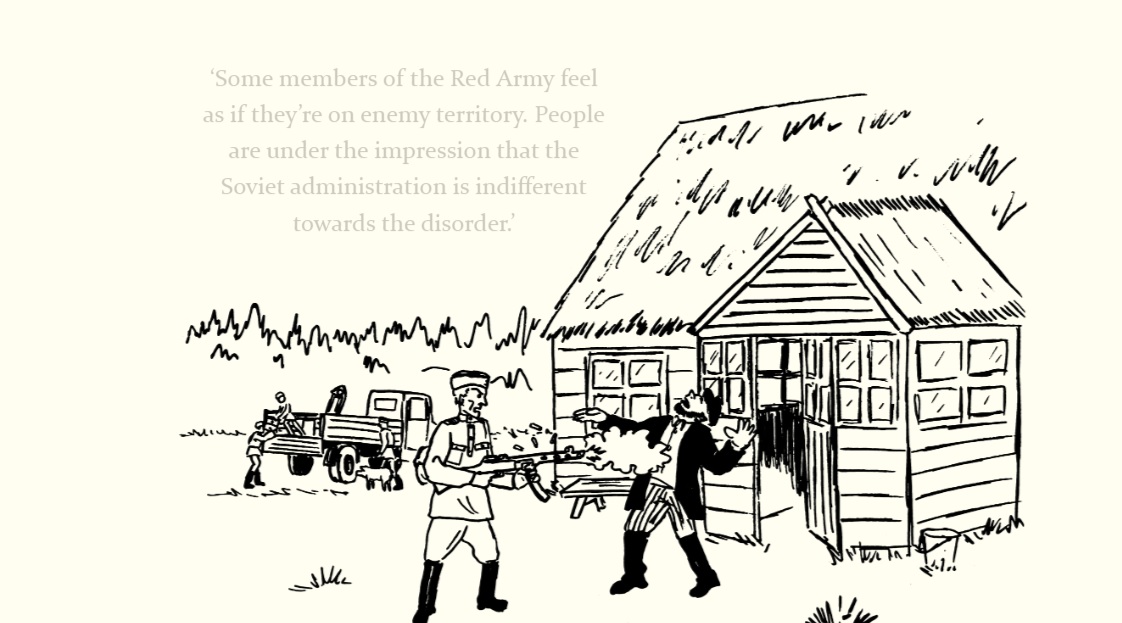

It became evident that it was hopeless to explain to the Red Army that they are not on hostile territory, but in a so-called Soviet Republic that was liberated from German occupation. Aggression in conquered areas was fuelled by the political propaganda that spread among the soldiers.

This is characterised by an excerpt from the statement by Nikolai Karotamm, the 1st Secretary of the Central Committee of the Estonian Branch of the Communist (Bolshevist) Party of the USSR, on 6 September 1945 at the meeting of the Bureau of the Central Committee: "Deputy Prosecutor of ESSR Comrade Udrits wrote to me saying that if the tribunal convicted a Red Army soldier, then the latter declared, how is it that I’m on trial because of an Estonian?"

This is perhaps an individual case, but also quite typical. One of the leading officials on censorship has announced that in a conversation with [the name has not been entered to the stenographic record], the latter stated it’s possible to eradicate the Estonian people.’

After the annexation of Estonia, local communists’ reports and letters, that reached the Kremlin, immediately followed, describing a wave of (war)crimes that accompanied Red Army’s advancement, such as murders, rapes, robberies, public thefts, drunken disturbances, disorder etc. Civilians as well as public buildings fell victim to daily violence, looting, misappropriation and property damage.

The lawlessness was inflicted not only by individual soldiers, but by the military authorities as a whole, who were either reluctant or unable to stop it. The misrule initiated appropriation of houses followed by evictions of former inhabitants or institutions, illegal duties to provide conveyance, fish poaching, unauthorised logging (including peculation of the end product as well as burning valuable park forests, fences and planks) etc.

The correspondence between local and military authorities demonstrates that they were utterly incapable of putting a stop to the looting – the former could not and the latter were either unable or unwilling to do so. It is known that the culprits were punished in a small number of cases. The soldiers protected their own and sometimes justified their activities or inactivity. It was even claimed that local “bandits” were behind the pillaging.

The correspondence also indicates that only a small part of the looting and violence went on record, especially in 1944. Most of the civilians saw no point in protesting, or there was no one to complain to, or people were simply scared because the despoilers were armed, and it was clear that the complaints of Soviet regime’s local offices were inconsequential.

On the one hand, USSR participated in crushing Germany; on the other, no liberation followed in conquered areas, one bloody dictatorship simply replaced another. For decades, all of this has been accompanied by controversial propaganda, which emphasises the “Red Army, the Liberator’s” role of in defeating Nazism, while the reality was quite different.

Excerpt from the report of Chairman of the Council of Deputies of the Working People of Saaremaa County to the ESSR Council of People’s Commissars’ Head of War Department on 10 January 1945 (RA, ERA.R-1.13.1, 249 - link at the Estonian National Archive). Unofficial translation.

I hereby report the disorderly conduct carried out by the soldiers in Saare County:

-

Polkovnik Zigorev reserved three apartments for himself, including one belonging to the inspector of local schools, who still has no apartment.

-

Men from Muhu municipality went to the mobilisation committee in Pöide. The military checkpoint at the end of Orissaare Bridge “checked” their watches, pocket watches, pocket knives etc. (The complaint was made by Mihhail Mereäär from Võlla village, Muhu municipality)

-

Personal belongings are confiscated from persons coming to town and to the market under the pretext of an inspection. (Report by the town’s Chairman of the Executive Committee)

-

Fisherman Oskar Jõeäär, living in Kihelkonna municipality, Loona village, protests that local border guards command him to hand over 40% of his fish. If he does not abide, he is no longer permitted to fish.

-

On 28 November 1944, 80-year-old Helena Pruul was killed by soldiers in Muhu parish, Lalli village. Her farm had been robbed five times.

-

Before New Year’s Day, soldiers in Kuressaare killed clocksmith Täht’s wife and gravely injured clocksmith Täht. All clocks in the clocksmith’s workshop were stolen.

-

On 28 November 1944, 18-year-old woman was raped and killed on Pähkla Rd. in Kuressaare (NKVD chief has the investigation file). An old man who tried to stop the soldiers was nearly beaten to death.

-

Kuressaare Post Office worker Aleksander Vahstein was shot by a senior lieutenant with the aim of stealing a watch. The shot penetrated Vahstein’s hip.

-

The Chairman of the Executive Committee of Kihelkonna municipality was robbed on a road by soldiers. Likewise, Mustjala Executive Committee Chairman’s house was broken into and various foodstuffs were stolen.

-

“Säde” guest house in Kuressaare housed a local military headquarters. The furniture of the guest house was taken when the HQ relocated. The Housing Department Executive Committee’s Head Vetela went to tell the soldiers off and later brought Commander Zaritsky along. The latter replied that he could not do anything about it, and thus facilitated the removal of the guest house's furniture by the soldiers.

-

In Pöide municipality, the Head of the Pöide Dairy Society by the name of Oll allowed a soldier to spend the night at his house. However, at night the soldier mysteriously disappeared, taking a bayan belonging to Oll with him.

-

There are countless soldiers out and about who rob residents’ foodstuff, equipment and animals from their barns.