Prisoners of the Solovetsky Islands. Part II: “Re-education”, Executions and End of the Camp

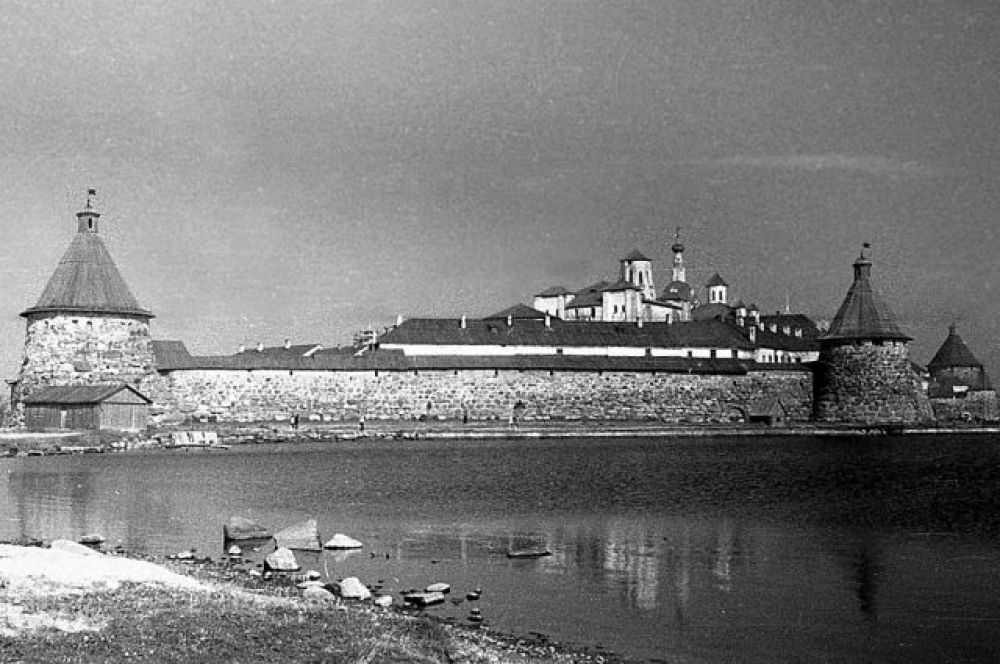

Irina Flige is a Russian historian. In this article she provides an insight into one of the most infamous Soviet prison camps, located on the territory of a former monastery on the Solovetsky Islands. In part 2 the author describes the beginning of the end of the camp. The Stalin era did not leave the Solovetsky Islands unaffected, as the nature of the communist Soviet Union became ever more inhuman. Every expression of intellectual activity was forbidden, extremely strict internal rules were imposed, and mass executions of political prisoners began. Read part 1 of the article, describing life in the camp from 1922 to 1929 here.

1929-1936: from Re-education to Isolation

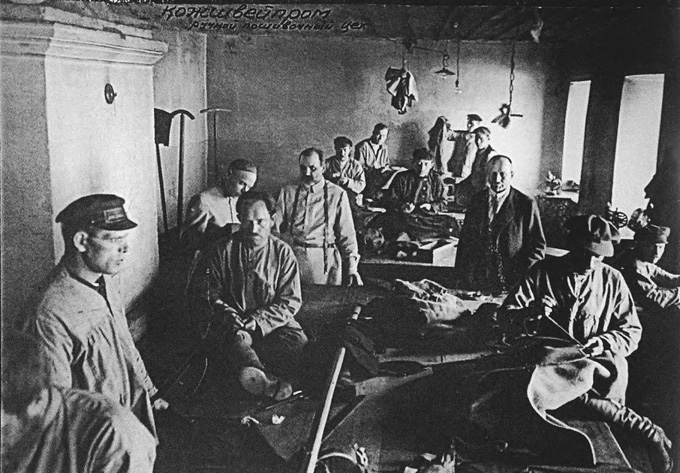

“The Great Turn” led to sweeping changes in the life of the detainees, with stricter camp regime and gradual withdrawal of the freedoms that the Solovki prisoners had enjoyed earlier.

The spring of 1930 saw the process of removing the so-called CRs, i.e., counter-revolutionaries from the various management and commercial posts in the camp administration. These were now taken over by former employees of the OGPU and “social allies”, i.e., common criminals.

Guards started to escort the prisoners to and from work. The prisoners were no longer allowed to wear their own clothes, instead mandatory camp uniforms were introduced. Their hair had to be cropped by a machine and faces had to be clean-shaven; these rules were compulsory for all prisoners, including the military.

A special permit had to be obtained every time for visiting the Onufri church, and two years later the church was closed for services altogether. The catholic services had been forbidden back in 1928 already and the priests were sent to carry out religious services in the catacombs on Anzersky (Anzer) Island.

The Solovki cultural and research activities also saw a downturn: in 1929 the Society for Local Lore was closed, in February 1930 the last issue of the journal “Solovetskie ostrova” came out, and the repertory of the theatre dried up. During this period (1929-1931) the Solovki camp was made part of the large Karelia-Murmansk group of camps, first bearing the name of Solovetsky Correctional Labour Camp, then Solovetsky and Karelia-Murmansk Camps, and then again Solovetsky Correctional Labour Camp.

In spring 1930 the USA, Canada and France imposed an embargo on the import of timber from the Soviet Union; as a result, logging in Karelia lost some of its economic significance.

In 1931 the construction of the White Sea-Baltic Canal began. On 16 November 1931, the Solovetsky Correctional Labour Camp was reorganised and became BelBaltLag (White Sea-Baltic Camp). However, on 1 January 1932, the Solovetsky part of the camp, which had nothing to do with the construction of the canal, was reorganised once again and became a separate small camp, bearing its original name, the OGPU Solovetsky Camp.

The detainees started to be transferred from the islands to the mainland, among them were criminal offenders, petty criminals and those serving a short sentence – anyone be able to engage in physical work. They were replaced by “especially dangerous” criminals who had been convicted on political charges and were serving long sentences. During this period prisoners belonging to the “special contingent” started to serve in isolation in Solovki: among them were the Trotskyists, Zinovyevists, Ukrainian nationalists, but also disabled persons and persons of poor state of health.

In November 1933, the Solovetsky camp was once again made part of BelBaltLag and became its Special Correction Department No 8.

At the time production activities in Solovki came to almost a standstill, focusing only on meeting the camp’s own needs, with prisoners engaging in agriculture, obtaining firewood (mostly driftwood), road construction and repairs. Orders from outside the camp were limited to the “iodine business”, collecting seaweed for extracting agar-agar and the leather industry. The latter business shrunk considerably after transfer to the Gulag capital Medvezhyegorsk on the mainland.

1937-1939: Isolation and End

On 20 February 1937, the status of the Solovetsky Department of BelBaltLag changed again: it was brought under the authority of NKVD GUGB (Main Directorate of State Security) Department No 10 (Dept. of Prisons) and named the Solovetsky Special Purpose Prison. It was classified as a prison of strict regime. In August there were approximately 2,400 detainees, they were placed under prison regime and locked up in the Kremlin buildings on Bolshaya Muksalma, and Anzersky (Anzer) Island.

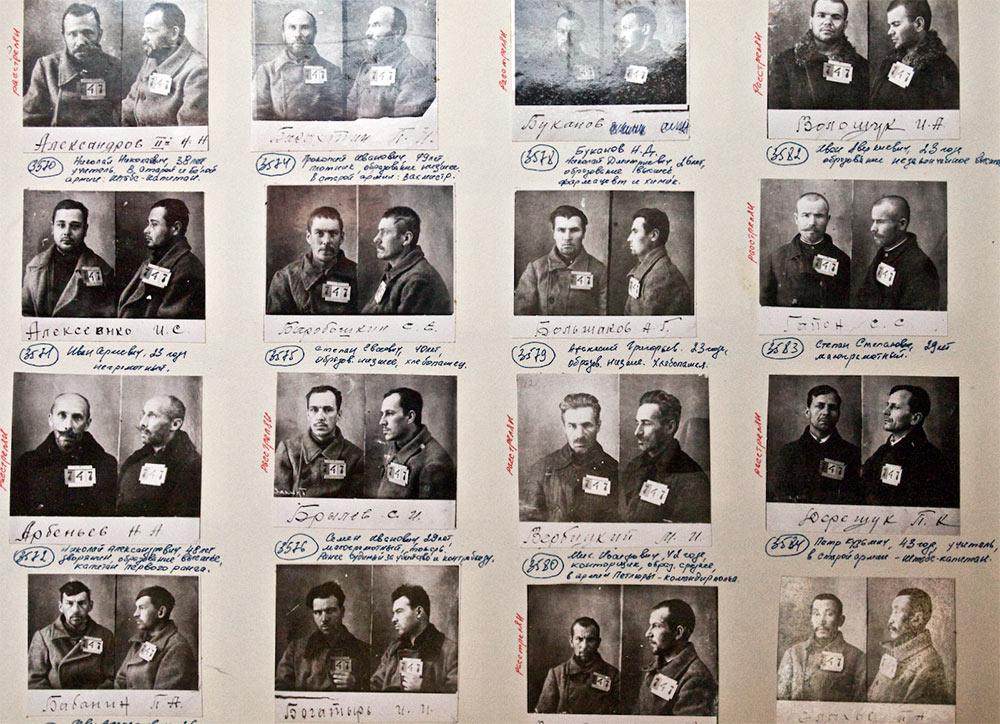

On 16 August 1937, People’s Commissar for Internal Affairs Yezhov issued Order No 59190 and annexes thereto, establishing a “limit” for the Solovetsky prison. Based on this, the “troika” of the NKVD directorate of the Leningrad Oblast sentenced 1,825 Solovetsky detainees to death by shooting and carried out the sentences from October 1937 to February 1938 (1,111 persons were shot in Sandarmokh, Karelia, 509 in hitherto unknown locations on the mainland and 198 in Isakovo, on Bolshaya Muksalma).

After the mass shootings the numbers in Solovetsky prison were replenished with detainees from other NKVD GUGB prisons on the mainland, as well as with prisoners sent directly after having been sentenced.

The regime became even stricter. The detainees were robbed of their family names and instead, were assigned numbers, which had to be marked on their beds and walls above the beds. When sitting, eyes had to open and hands on knees, walks were limited to 30 minutes per day, letters were not handed out to the prisoners, they could read them just once, under the supervision of the guard.

In 1939 the construction of a new prison started on the site of a former brick factory of the monastery, about three kilometres from the Kremlin. The prison was designed for at least 3,000 detainees and was completed in 1939 but was never used for the purpose it was built. In summer 1939 the Solovetsky prison was closed and the prisoners were transferred elsewhere, e.g., the Norilsk, Ukhtinsko-Pechorsky and other camps.

On 2 November 1939, the Solovetsky prison was officially closed. Its territory became a naval cadet training base of the Soviet Northern Fleet.

Irina Flige (born in 1960) has been studying the repressions in the Soviet Union since the late 1980s. Since 2002 she has been Director of the Memorial Research & Information Centre in St Petersburg. Flige has played an important role in discovering and researching the burial sites of victims of communism in Russia. For example, Flige and her colleagues discovered the secret site in Sandarmokh, where victims of Stalin’s Great Terror had been buried.

Sources and Literature:

Бродский Ю.А. Соловки. Двадцать лет Особого назначения. – М.: 2008. – 528 с., ил.

Флиге [Резникова] И.А. Православие на Соловках. Материалы по истории Соловецкого лагеря. – СПб.: Издательство Научно-информационного центра «Мемориал», 1994. – 208 с.

Сошина А.А. На Соловках против воли: судьбы и сроки. 1923–1939. – Соловки; М.: «Издательство ТСМ», 2014. – 232 с. :ил.

Флиге И.А. Сандормох: драматургия смыслов. – СПб.: Нестор-История, 2019. – 208 с., ил.

Система исправительно-трудовых лагерей с СССР, 1923–1960: Справочник / О-во «Мемориал», ГАРФ. Сост. М.Б. Смирнов. Под ред. Н.Г. Охотина, А.Б. Рогинского. М: Звенья, 1998. – 600 с., карт. (Беломоро-Балтийский ИТЛ. – С.162-164; Соловецкий ИТЛ ОГПУ – С.394-397)

Memoirs:

Волков О. Погружение во тьму. Из пережитого. – Paris: Atheneum, 1987. – 447 p.

Чирков Ю.И. А было все так… – М.: Политиздат, 991. – 99. – 382 с.: ил.

Безсоновъ. Двадцать шесть тюремъ и побҌгъ съ Соловковъ. – Издание Imprimerie de Navarre (5, rue des Gobelins, Paris), 1928. – 228 стр.

Генерал-майор И.М.Зайцев. Соловки (коммунистическая каторга, или мҌсто пыток и смерти). Из личных страданiй, переживанiй, наблюденiй и впечатлҌнiй. В двух частях. (С приложенiем четырех планов.) – Шанхай, 1931 г. Типографiя издательства «Слово». – 169 стр.

Мих.Розанов. Соловецкий концлагерь в монастыре. 1922–1939 годы. Факты – домыслы – «параши». Обзор воспоминаний соловчан соловчанами. В двух книгах. Книга первая. Издание автора. 1979. [Место издания не указано, автор жил в США].

М.З.Никоновъ-Смородинъ. Красная каторга (Записки соловчанина) / Подъ редакцiей А.В. Амфитеатрова. – Софiя, Издательство Н.Т.С.Н.П., 1938 г. – 369 стр.

С.Пiдгайний. Украïнська iнтелiгенцiя на Соловках. Спогади 1933–1941. – Мюнхен: издательство «Прометей», 1947. – 93 стр.

Vladimir V. Tchernavin. I speak for the Silent. Prisoners of the Soviets. – Boston & New York, 1935. – 368 стр.

Г.Андреев. Соловецкие остров