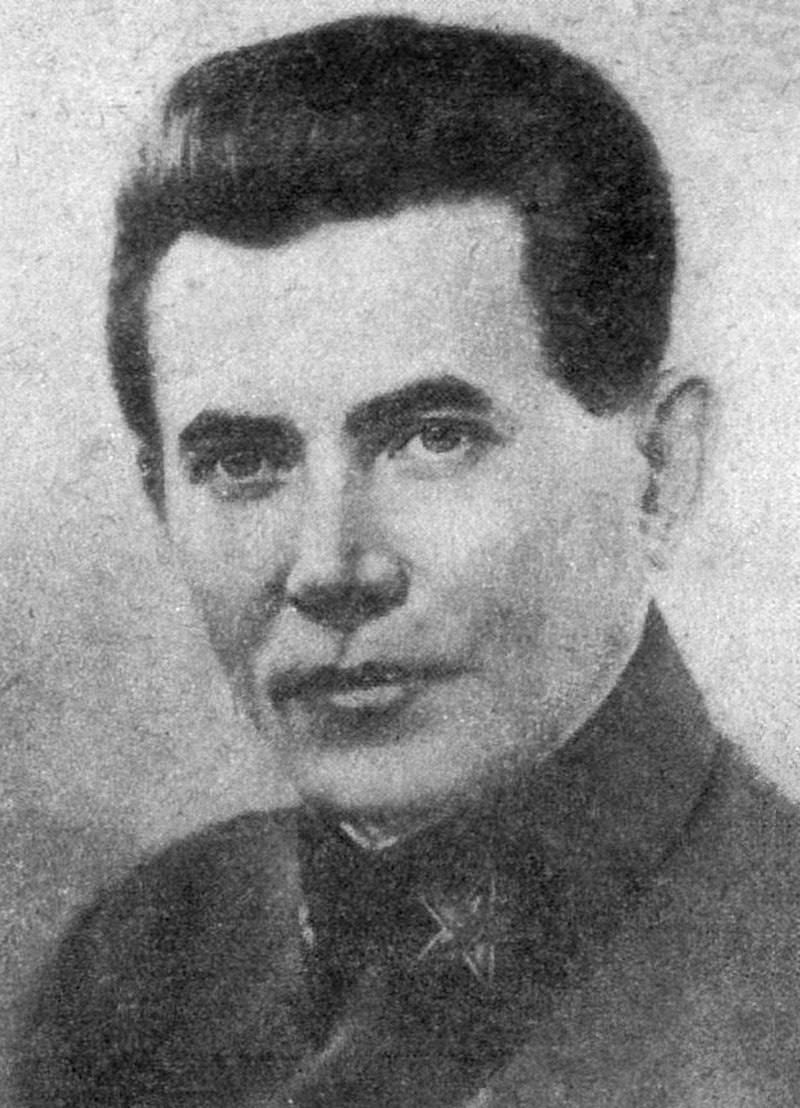

Nikolai Yezhov: A Portrait of the “Bloody Dwarf”. Part 1: Stalin's Favourite

Nikolai Ivanovich Yezhov (1895-1940) was, in his prime, the head of the infamous Soviet secret police, the NKVD, and a confidant of Stalin himself. He was a key perpetrator and the namesake of the Yezhovshchina, the Great Terror of 1936-1938, earning him the nickname “The Bloody Dwarf” in reference to his small stature. Despite his significance in understanding the crimes of communism in the Soviet Union, history typically gives little sense of Yezhov’s personality and how it fuelled the misery he unleashed on the Soviet populace.

In this two-part article, Australian historian Jesse Seeberg-Gordon takes a closer look at Yezhov’s life and the crimes he committed. Part 1 deals with Yezhov’s rise to power and role in liquidating many of Bolshevism’s oldest proponents. Part 2, to be published at a later date, addresses the mass arrests and executions overseen by Yezhov during the height of the Yezhovshchina, as well as his ultimate downfall.

For roughly two years, Nikolai Ivanovich Yezhov was the second most powerful man in the Soviet Union. He commanded a vast network of state terror through the Soviet interior ministry, the NKVD, and had the ear of Joseph Stalin himself. The latter commanded, and the former executed. Yezhov’s rule is remembered as an era of arbitrary arrest, fear, and mass murder. The Russian word for the Great Terror of 1936-1938, Yezhovshchina, is his namesake and legacy. Yet, the “Bloody Dwarf”, as Yezhov was known by some by reason of his short stature, eventually succumbed to the very blades of terror he himself had sharpened, as did many Bolshevik loyalists before him. Having rapidly fallen out of Stalin’s favour, and after being stripped of his rank and enduring multiple, torturous ‘interrogation’ sessions, he was shot as he begged for mercy.

As an individual, Yezhov was hardly a simple person. He could be charming when he wanted to, but was also sadistic and unstable. He could be both callous and, at times, more or less fair. His intricate personality and tase for rapacious violence distinctly influenced the events of the Terror. However, Yezhov, despite his rank and historical significance, is a mysterious entity. Though personally responsible for heinous mass killing, history typically gives little sense of who this man was, and how his intricacies, flaws, and clinical instability, fuelled his reign of terror.

The Man

Yezhov was born in 1895 to a forest warden and a maid. The future chief of the NKVD completed only a few years at primary school before he began working at the Putilov Works in Saint Petersburg. Standing at only 151 centimetres, he was nevertheless conscripted into the Tsarist Army in 1915, and after he was wounded in battle, returned to mend guns in Vitebsk. In the wake of the October Revolution of 1917, he joined the Red Army. Around this time, he met Lazar Kaganovich, a prominent Soviet politician who was later to become Yezhov’s ticket into Stalin’s inner circle.

Yezhov began climbing the ranks of the vast Soviet bureaucracy, and by 1930 he was attending meetings of the Politburo, the executive committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Throughout his various posts, he displayed an extraordinarily disciplined work ethic. A contemporary remembered him as a shy, thin man, suffering from tuberculosis. Dressed in a cheap wrinkled suit, he spoke little, ate little, and listened attentively. “You do not need to check his work”, the colleague admired, since “he will do it all”. Yezhov’s only problem was, he noted, that “he does not know when to stop”. Was this an omen?

He was well liked by many. Nikolai Bukharin, an Old Bolshevik who would later fall victim to Stalin’s machinations, described him as having a “good heart and clean conscience”. Although some authors portrayed him as intellectually dim, the Putilov workers remembered his penchant for constant reading, christening him ‘Kolka-Knizhnik’ (Nikolai the Bookman). Yezhov also had a voracious sexual appetite. Though popular with women, many of whom thought him handsome and playful, he was also known to sleep with men, effectively making him bisexual.

A darker entity lay beneath this charming image: A disturbed, anxious man who saw no reasonable boundaries to violence, his obedience to his superiors, or the methods he employed to achieve his goals. Here, his ‘positive’ traits were amplified to excessive, sinister ends. As he ordered mass murder on a weekly basis, he was regularly engaging in drunken orgies with prostitutes, and even his male comrades. On top of this, he had a troubling sense of humour. During these drinking bouts with his friends (many of whom would later lose their lives in the Great Terror), he would participate in farting contests, aiming to blow away ash from a coin lying on the floor.

The Favourite

On top of being an alcoholic, Yezhov suffered from chronic health issues, including myasthenia, anaemia, psoriasis, and what was then known as “neurasthenia”. This combination of compulsive devotion to his work, nervousness, a short temper, and physical frailty caused him periods of illness, depression, and exhaustion. He was frequently sent on leave to alleviate these ailments, including to luxurious retreats in Austria and other such ‘counter-revolutionary’ countries outside of the USSR.

The relationship between two senior Bolsheviks was almost like any close friendship. Stalin, as he often did with his favourites, gave Yezhov a nickname: yezhevichka, or “my little blackberry”. Stalin gladly welcomed Yezhov into his cadre in the early 1930s. He admired Yezhov’s exceptional work ethic, writing approvingly to him in August 1935 that “When you say something, you always do it!”

Stalin ensured Yezhov’s dedication was rewarded with various retreats and vacations when his health demanded it. When, in 1934, Yezhov had exhausted himself and was plagued with boils, Stalin had him sent away to receive high-end therapeutic treatment in Central Europe. Stalin’s message to the embassy in Berlin read: “I ask you to pay very close attention to Yezhov. He’s seriously ill and I cannot estimate the gravity of the situation. Give him help and cherish him with care […] He is a good man and a very precious worker”. Such treatment sometimes came despite Yezhov’s protestations; Stalin was cultivating his ‘little blackberry’. Of course, Stalin did not keep Yezhov close simply because he enjoyed his company.

The Backstabber

Yezhov was instrumental in Stalin’s consolidation of power, effectively enabling his rise as the unchallenged dictator of the Soviet Union. He did this by helping Stalin eliminate any and all political opposition amongst the Soviet elite, both real and imagined, under the guise of state security and a ‘war’ against internal enemies.

Yezhov rose to prominence at the beginning of the Terror, which was initiated by the murder of Sergei Kirov, the Party head of Leningrad and a close associate of Stalin, in December 1934. Though the perpetrator was a crazed gunman who acted independently, Stalin used the event as a pretext to eliminate any ‘unreliable’ figures from the complicated chessboard of internal politics. Kirov’s death rendered the killing of so-called ‘conspirators’ necessary, and in the context of Soviet totalitarianism, this could only mean a swift campaign, measured in lives by the thousands.

Just hours after Kirov’s murder, Yezhov was supervising the NKVD in arresting lists of suspects drawn up by Stalin. He initially cooperated with Genrikh Yagoda, who was still nominally head of the NKVD, to prosecute the Old Bolsheviks Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev and their associates on fabricated charges of a “counter-revolutionary” Trotskyite plot to kill Stalin. Signifying his commitment to the task at hand, Yezhov even wrote one chapter of a future book about this Zinovievite ‘conspiracy’, which was edited by Stalin himself. Yezhov never finished writing the book.

The case culminated in the first of three Moscow Show Trials in August 1936. The ‘evidence’ collected against the accused was completely fraudulent. Yezhov tortured them with sleep deprivation, heat exhaustion, and threats, especially to their families. Friends of the accused, and Zinoviev and Kamenev themselves, were promised their lives in return for their cooperation. They were, nonetheless, executed after the inevitable guilty verdict was returned. Yagoda kept souvenirs in the form of the bullets that killed Zinoviev and Kamenev, which were extracted from their heads.

This working relationship between Yezhov and Yagoda was not to last. Yagoda was rapidly falling out of favour with Stalin who, at one point, threatened to “punch him in the nose” if he did not rectify his alleged professional inadequacies. In September 1936, Yezhov finally succeeded him as the People’s Commissar for Internal Affairs, a move which some, including Bukharin, believed could signal an end to the Terror. Bukharin, who would soon fall victim to the devices of Stalin and Yezhov, could not have grasped just how wrong he was.

Stalin carried on with his objective of liquidating anyone he believed, or at least claimed to believe, ‘threatened’ his rule. In this task, the NKVD, with his Blackberry at the helm, would be his personal instrument of destruction.

After all, for Stalin’s executioners, killing enemies was simply fun. In December 1936, at a celebration for an NKVD anniversary, head of the security department Karl Pauker, who was known for his artistic side, threw a stand-up comedy scene for Stalin and his high-ranking guests, Yezhov among them. Held by two husky NKVD goons, a drunken Pauker took to imitating Zinoviev’s final minutes, when he was being dragged from his cell to his execution. Pauker fell to his knees and, hugging the feet of his ‘executioners’, wailed: “Please… For God’s sake, comrade… Call Iosif Vissarionovich [Stalin]!” A roar of laughter exploded in the room like a shell. Stalin laughed, too.

The audience, seeing the reaction of their leader, demanded an encore, egging Pauker on. This time Pauker added a religious overtone, at the peak of the scene throwing his arms to the ceiling and, in reference to Zinoviev’s Jewish heritage, yelled: “Hear O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is One!” Stalin, exhausted, could not laugh anymore, and waved his hand for Pauker to stop. It was a good night. Sweaty, smiling Pauker had less than eight months left to live.

Jesse Seeberg-Gordon is an Australian historian whose primary interest is the Soviet Union and its successor states. He graduated from the University of Melbourne in 2020, where his honours thesis, which dealt with an Australian-Soviet diplomatic incident in the 1970s, won the Brian Fitzpatrick Prize for Best Honours Thesis in Australian History. He currently works as an intern with the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory.

List of Sources

Alexander Orlov. The Secret History of Stalin’s Crimes. New York: Random House, 1953.

Geoffrey Hosking. A History of the Soviet Union, 1917-1991: Final Edition. London: Fontana Press, 1992.

Nikita Petrov & Mark Yansen. Stalin’s Fosterling - Nikolai Ezhov. Moscow: Rosspen, 2008.

Simon Sebag Montefiore. Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar. New York: Vintage, 2007.