Mythbuster: Why the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939 was not ‘forced’ on Stalin

On August 23, 1939, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed the ‘Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics’. Colloquially known as the ‘Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact’, this agreement, hailed by the Soviet press as “an instrument of peace”, was ostensibly a mere non-aggression treaty.

In reality, however, it immediately precipitated the outbreak of World War 2 in Europe while satisfying the expansionist goals of the Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin. In this myth buster article, we address the popular myth that Stalin’s deal with Hitler was ‘forced’ on Stalin by circumstances beyond his control.

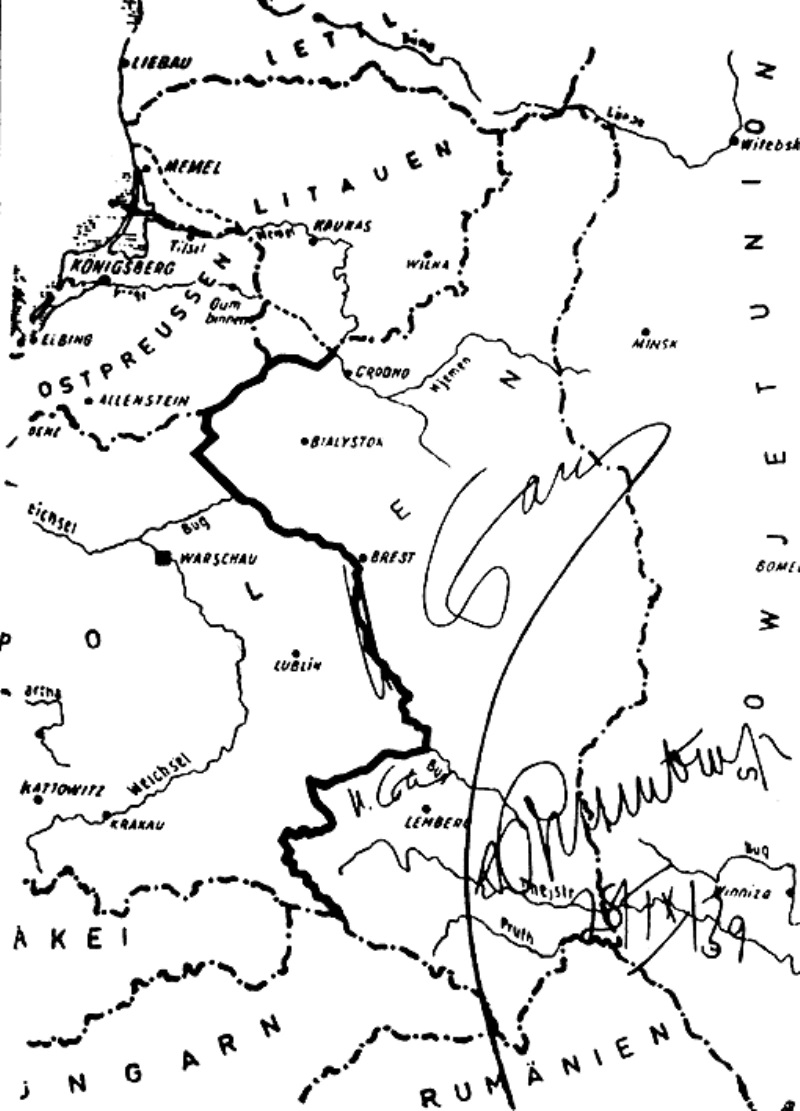

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was both a blatant violation of international law and the catalyst for World War 2 in Europe. A Secret Protocol within the agreement divided parts of Eastern and Northern Europe into spheres of influence “in the event of territorial-political reorganization” of these regions. This thinly veiled agreement to apportion the spoils of Europe relegated Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and parts of northern Romania to the Soviet sphere, with Poland being split between the Soviet and German spheres.

On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland, with the Soviet Union following suit sixteen days later. Countless atrocities, committed by both totalitarian powers, soon followed in the newly occupied territories.

Over eighty years on, disinformation about Stalin’s ‘deal with the devil’ is rampant. Perhaps the most prominent of these myths is the notion that Stalin was somehow ‘forced’ to sign the Pact. This myth has no basis in historical fact, and can be dismissed through a careful examination of the geopolitical historical events concerned.

A Stalinist Myth

Stalin himself was a chief architect of this myth. After the war, he pointed his finger at the West for conspiring against the Soviet Union in pre-war negotiations for a collective security alliance against Hitler, and for enabling Hitler’s march eastward through appeasement of his territorial ambitions. This, Stalin claimed, had ‘compelled’ the Soviet Union to deal with Hitler in a ‘brilliant’ work of statesmanship that circumvented Western conspiracy. The Secret Protocol was simply dismissed as a Western fabrication, a denial which continued until 1989.

This myth persists decades on, though with some key differences. Today, the Pact is contextualised within the pre-war sphere of international relations as a ‘normal’ course of action. Instead of being outright denied, the Secret Protocol is embraced as a necessary response to Western appeasement, particularly the Munich conference of 1938 at which the West ceded the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia to Hitler in exchange for promises of peace. This embodiment of appeasement failed miserably when Hitler went on to seize Bohemia and Moravia, dispelling any hopes that Nazi expansionism could be satisfied.

The West, it is claimed, evidently preferred to cooperate with fascism rather than unite with the Soviet Union to destroy it, a treachery which forced Stalin to ‘beat the West at its own game’.

The Proponents

Among the greatest proponents of this myth is the state of the Russian Federation. The Russian President himself remarked in 2019 that “the Soviet Union agreed to sign [the Pact] only after all other avenues had been exhausted…”. Russian state media and various public service branches (such as Russian embassy twitter accounts) also contribute.

Furthermore, a string of recent legislations in Russia has outlawed historical narratives about the German-Soviet War (the ‘Great Patriotic War’, as it is known in Russia) that contradict the ‘correct’ official line, endangering debate about the Pact and its ramifications.

Busting the Myth

This myth deflects responsibility for the Pact by ignoring several key historical details. Chief among these is the weak analogy between the Munich conference and the Pact. The failures of appeasement were indeed catastrophic. But, whereas Munich was an inept attempt at avoiding war from which Britain and France gained nothing territorially, the Pact was an opportunistic, mutually beneficial agreement between two dictatorships that would certainly lead to war.

Stalin could not have been ‘forced’ to strike a deal with Hitler when other options did exist. Most important among these was the very real possibility of a military alliance with the West. Anglo-French-Soviet negotiations conducted prior to August 23 were certainly clumsy, but were not insincere. This did not stop Stalin from gloating that the Western delegations in Moscow, still unaware of the Soviet-German agreement, were “going to leave empty-handed”.

Far from being pushed towards Hitler, Stalin was capitalising on his ‘generosity’ in allowing the Soviet Union to stay ‘neutral’ in the looming conflict while furthering Soviet territorial ambitions. The product was an aggressive war against Finland in winter 1939-1940 and the deportations and executions of hundreds of thousands of ‘politically suspect’ people in the annexed territories.

Stalin’s cynicism and dogmatic Marxist-Leninist worldview caused him to underestimate the West’s resolve to oppose Hitler after the failure of Munich became apparent. The capitalists and the fascists, he believed, were simply two sides of the same coin.

“A war is on between two groups of capitalist countries” he told his inner circle on September 7, 1939. “We see nothing wrong in their having a good hard fight and weakening each other”. The destruction of Poland, he claimed, even presented an opportunity to “extend the socialist system onto new territories and populations”.

The Soviet Union further benefited from its alliance with Hitler through German loans, used to purchase machinery and military technology from the Reich. In turn, the Soviet Union shipped massive sums of raw materials to Germany, frustrating the West’s naval blockade of Stalin’s fascist ally, while also keeping German-Japanese trade alive via the trans-Siberian railway. Ultimately, it was Germany that benefitted more from Soviet-German economic cooperation by a margin of over 200 million marks; Stalin, having thwarted a prospective anti-Hitler alliance, instead fuelled Hitler’s war against the West.

Myth Busted

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was no ‘brilliant’ work of foreign policy forced on Stalin by geopolitics. This decades-old Soviet myth only reinforces the appeasement philosophy that Hitler should not have been resisted, but dealt with through territorial concessions. Unlike Western deals with Hitler, however, Stalin took concessions as well as gave them. Stalin’s complicity with fascist warmongering as a means of progressing red imperialism and making Hitler ‘the West’s problem’ eschewed Europe’s best hope at avoiding war. The fact remains that the same anti-Hitler coalition that came into existence in 1941 could have come to fruition in 1939, had Stalin willed it.

List of sources and further reading

Banerji, Arup. “Notes on the Histories of History in the Soviet Union”. Economics and Political Weekly 41, no.9 (Mar. 4-10, 2006): pp.826-833.

Benn, David Wedgwood. “Russian Historians Defend the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact”. International Affairs 87, no.3 (May 2011): pp.709-715

Carley, Michael Jabara. “Fiasco: The Anglo-Franco-Soviet Alliance That Never Was and the Unpublished British White Paper, 1939–1940”. The International History Review 41, no.4 (2019): pp.701-728.

Clark, Lloyd. Kursk: The Greatest Battle, Eastern Front 1943. United Kingdom: Headline Review, 2011.

Edele, Mark. “Fighting Russia’s History Wars: Vladimir Putin and the Codification of World War II”. History & Memory 29, no. 2 (Faller/Winter 2017): pp.90-124.

Edele, Mark. Stalinism at War: The Soviet Union in World War 2. London; New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021.

Finney, Patrick. Remembering the Road to World War Two: International History, National Identity, Collective Memory. New York: Routledge, 2010.

Manne, Robert. “Some British Light on the Nazi-Soviet Pact”. European Studies Review Vol. 11 (1981): pp.83-102.

Mitrovits, Miklós. “Background to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact: Legends and Facts”. Central European Horizons 1, no.1 (2020): pp.17-32.

Murphy, David E. What Stalin Knew: The Enigma of Barbarossa. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005.

Nation, Craig R. Black Earth, Red Star: A History of Soviet Security Policy, 1917-1991. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992.

President of Russia. “CIS Informal Summit”. Published December 20, 2019. http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/62376

Pons, Silvio. Stalin and the Inevitable War: 1936-1941. Portland: Frank Cass, 2002.

Savisaar, Edgar. “Keeping Faith with Estonia”. In Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact: Challenging Soviet History, edited by Heiki Lindpere, pp. 80-93. Tallinn: The Foreign Policy Institute, 2009.

“Secret Supplementary Protocols of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Non-Aggression Pact, 1939”, September 1939. History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, published in Nazi-Soviet Relations, 1939-1941: Documents from the Archives of the German Foreign Office. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/110994