Marxist Cultural Revolution and International Cultural Policy, Part One

A new and unique „Soviet people” was to be the ultimate product of the cultural revolution and education in internationalism, says historian Peeter Kaasik.

„The socialist national culture” took its form in the course of the „cultural revolution”. This was a term that in Soviet jargon could be defined as follows: „Cultural revolution is a long-term process of revolutionary changes in the intellectual life of the society, which is led by the socialist state and takes place with the active participation of the whole nation.”

Note that the emphasis is on the „process led by the state”, i.e., there is nothing spontaneous or evolutionary about the process. And there is no need to pay any attention to the other half of the definition about the „active participation of the whole nation”, for the totalitarian regime did not tolerate any popular initiative, even if it kept preaching it.

The „cultural revolution” in communist China took a really sinister form.[i] In the Soviet Union the cultural revolution was considerably more modest, but in addition to direct repressions, still involved sadistic elements similar to the Chinese methods, i.e., creative persons were made to publicly repent their sins and renounce their work, write self-critical letters of apology, and heavily criticise their colleagues.

In general, anything that was in stark contrast to the earlier cultural activities was favoured after the revolution. However, no common approach existed. The 1920s were an era of various groups, both in literature and visual arts. Some groups were clearly apolitical (the imaginists), whereas others – proletarian. There were also those who did not belong to any group but were tolerated nevertheless („poputchiks”). The best known among them was probably Mikhail Bulgakov.

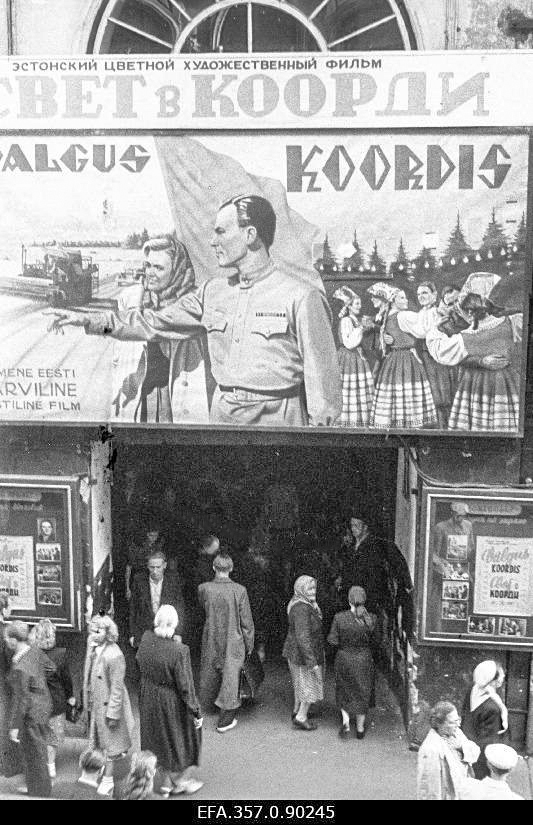

The two most influential proletarian groups were „Lef” („Left Front”) and „Proletkult” („Proletarian Culture”). Vladimir Mayakovsky was the leading figure of „Lef”, and other well-known members of the group were Boris Pasternak, the futurist poet Velimir Khlebnikov, and film director Dziga Vertov. The „Lef” movement represented propagandist street art. Its principal genres were the slogan, propaganda, and documentary film. They responded to the so-called social commission, aiming to promote new ideas and contributing to the construction of the „new world”.

„Proletkult” was established in 1917. The leading bolshevist cultural theorist Anatoly Lunacharsky was the author of the idea. In addition to him, Alexander Bogdanov and Aleksei Gastev were the main ideologists of the group. The focus was on class consciousness of art, for according to them, people apparently had no other consciousness but that of class. Only proletarians were to create art (although the majority of the members of the group did not have proletarian background).

Only the most „progressive” traditions were to be taken over from the previous culture. But sometimes this led to serious exaggerations, criticised even by the bolshevist leaders. One such was the idea to liquidate literacy instead of liquidating illiteracy in order to achieve equality! As regards human relationships, they emphasized that the family would have no place in the new society and children would be raised by the society. Proletkult had its own ideas about „proletarian language”, which in principle meant the use of the „telegram style” and which later evolved into pseudo-scientific „materialist linguistics”. According to the latter, language depended on the ideology of Marxist class struggle.[ii]

Later, professional bodies started to be formed, with names like RAPP – the Russian Association of Proletarian Writers; RAPM – the Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians; AHRR – Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia; AHR – Association of Artists of the Revolution; RAPH – Russian Association of Proletarian Artists.[iii] These organisations were characterised by the rejection of the bourgeois cultural heritage and their principal objective was the production of „proletarian culture”, which had to diverge from the earlier cultural tradition.

At the beginning of the 1930s such „cultural clowning” with no proper rules was stopped, as it was deemed inappropriate for the socialist state and incomprehensible for the listeners and viewers. Instead, the canon of socialist realism was introduced. This is the definition of the communist cultural theorist A. Yegolin:

„Socialist realism evolves on the basis of the proletarian and revolutionary struggle, and in its subsequent development is supported by the experiences of constructing socialism. Socialist realism calls for comprehensive description of the reality in its revolutionary development. The method of socialist realism means that authors must be guided in their work by the ideas that encourage the people to fight for the construction of communism. [...] Socialist realism differs from realism in that it can clearly see the governing trends in the development of the real world and therefore is extremely powerful in securing the new and rejecting the old.”[iv]

Thus, no attempt was made to hide the fact that artistic excellence was of secondary importance and that the educational role of socialist culture was paramount. Cultural revolution was important for the purposes of national policies and education in internationalism, primarily because the formation of a socialist nationality was a process where these components depended on and complemented each other. „Universal communist culture” was to be the final product of the cultural revolution.

Although it was difficult to plant culture into the concept of class struggle, the Soviet propaganda experts found a way. They claimed that the social content of culture was primarily expressed in the reflexion of the governing mode of production, as an indication of the class interests and ideological beliefs of the society. In other words, the form of culture was determined on the one hand by its socialist content and on the other hand by its ethnic characteristics (i.e., the conditions and specific features of developing a nation).

For the purposes of class struggle, national culture could only emerge along with the capitalist socio-economic formation and was subject to its general laws. But then, in a class society, culture also acquired „class characteristics” – the national culture in the capitalist society reflected the class conflicts inherent in capitalism. The national form expresses the two different contents of culture in the capitalist society – the bourgeois and the proletarian. As a result, culture was divided into two antagonistic parts, connected, though, by a common national form, but expressing different interests and ideologies. Thus, according to the Leninist principle, „there are two nations in every modern nation, and there are two kinds of national culture in every national culture”. This is how Lenin saw this:

„The elements of democratic and socialist culture are present, if only in rudimentary form, in every national culture, since in every nation there are toiling and exploited masses, whose conditions of life inevitably give rise to the ideology of democracy and socialism. But every nation also possesses a bourgeois culture (and most nations a reactionary and clerical culture as well) in the form, not merely of “elements”, but of the dominant culture. Therefore, the general „national culture” is the culture of the landlords, the clergy and the bourgeoisie.”[v]

Thus, in the capitalist society, the dominant culture is that of the „exploiters”. In culture it took the form of „going after profit”, „keeping the working masses in intellectual darkness”, and preventing the above masses from enjoying the fruits of culture. All this for one simple reason – exploitation in this way was safer and more profitable. On the one hand, the „keeping in darkness” was related to religion and on the other hand, promoting the lower forms of culture (i.e., accessible to the workers). The opposite to this culture was „the progressive and fighting culture of the exploited masses”.

There were periods in the Soviet history when the gap between the new and the old was seen as entirely insurmountable, but in the post-Stalinist era the understanding came that it was possible to take over some progressive elements from the „bourgeois culture”, and by using the „socialist critical mind”, the bourgeois culture could even be consumed in moderate quantities. A special term, „democratic culture”, was coined to describe this intermediate category of culture. It was seen as a trend in culture, which had broken away from bourgeois culture, but had not yet become revolutionary, merely limited to a critical attitude towards bourgeois ideas. In general, this was a form of culture, which was neither here nor there and would tend to slide towards the bourgeois rather than the proletarian culture.

Since theoretically capitalism was doomed, the „bourgeois nation” had to be transformed into a „socialist nation” (or „people”). The formation of the bourgeois nation took a long time, at worst even several centuries. There was no such problem with the socialist nation, for in the case of the Soviet Union the process only took some decades to be completed. A new socialist economic life emerged, which also led to a new psychological make-up of a nation.[vi] These were the preconditions of achieving a higher qualitative level in the field of culture, i.e., for the „socialist national culture” to triumph. Theoretically this culture was characterised by „proletarian humanity, was socialist, international and expressed the interests and aspirations of the people, was created by the people for the people”. When picked apart, this vague theory means that the earlier cultural heritage was subjected to a critical analysis, taking over only the „progressive” elements, and throwing out everything „obsolete and reactionary” (like religion, idealism, cosmopolitism, nationalism, formalism etc). The general concept of socialist realism also derived from this – „socialist in content – national in form”, reflecting the socio-economic progress of a nation constructing communism.[vii]

Lenin’s argument that every culture contained some valuable and progressive elements and anything obsolete had to be destroyed, was used to evaluate the history of nations and their cultural heritage. In the Stalin era this meant the liquidation of national culture and national intelligentsia, destruction of historical monuments, documents, and books, as well as distortion of history, suppression of certain events and persons, attempting to eliminate anything deemed „unsuitable” from the memory of people and using educational and cultural policies and aggressive propaganda to achieve these aims. Things did not improve much after Stalin, although more refined ways were used to eradicate national consciousness and physical destruction was replaced with methods to ruin the spirit of the people.

According to the ideology, the possibilities for the development of nations would come to an end. The mass consciousness was stuffed with demagogy:

- Ethnic differences will disappear, but nations remain;

- A change in mother tongue is not accompanied by a change in national identity;

- Internationality will not replace nationality.

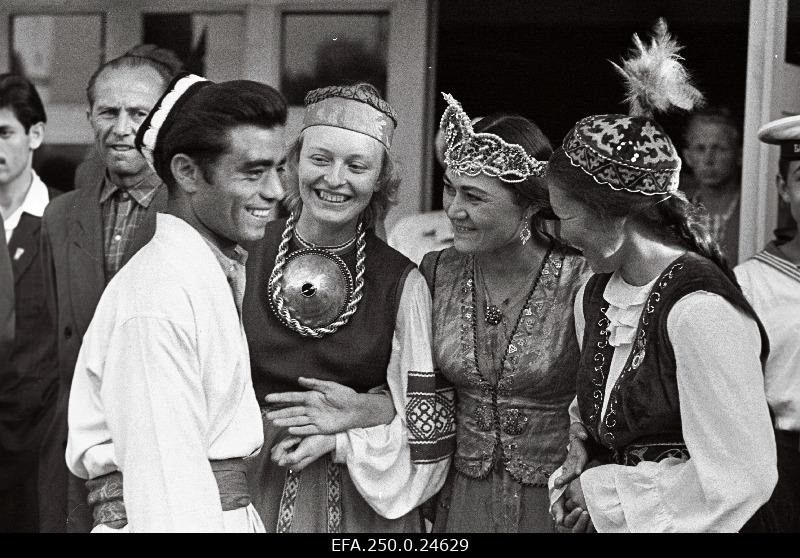

On the contrary, according to the theory, the situation of national cultures was to improve as a result of these changes. The concept of nationalism did not distinguish between the small and large nations, i.e., national consciousness of the small and chauvinism of the large nations. No attention was paid to the fact that in principle, the nationalism of a large nation always means an attack on the values of other nations, whereas the nationalism of a small nation is aimed at defending its own national values and they have practically no possibilities of attacking those of a large nation. As a result, integration of an alien culture into national culture was made mandatory and the process was called international cultural revolution. Any opposition was deemed nationalism in its negative sense.[viii]

Homo Sovieticus – the Ultimate Goal of the Cultural Revolution and Education in Internationalism

A new and unique „Soviet people” was to be the ultimate product of the cultural revolution and education in internationalism. The phrase was lifted from the meaningless resolutions of the communist congresses to become an important term in the vocabulary describing national relations. Ethnicity was recognised only to the extent that a particular nation had contributed to creating the new Soviet people. Obviously, they all gave their share, but in particular, „the great Russian nation”. The totalitarian Soviet society emphasised „unity”, „equality”, „conformity” etc. Ideally everyone in the state (and in the future also in the whole world) should speak one language and think alike.

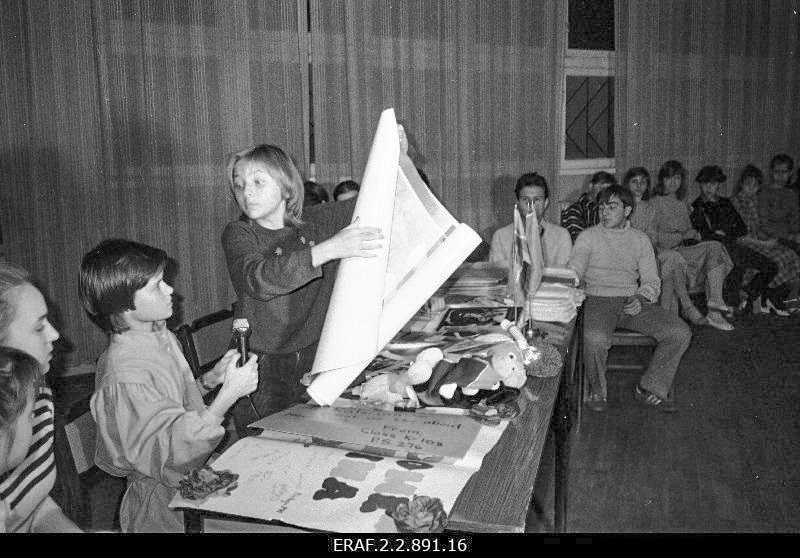

To achieve this goal, it was necessary to develop the „consciousness of the Soviet man”. There were several components to this:

- Moral consciousness, to help distinguish between the right persons and historical events, and the wrong ones (i.e., the Soviet source criticism, taught as part of the various „red subjects”). The positions of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union had to be adhered to, and they were not subject to appeal;

- Socio-economic consciousness, to understand inequality between people and create an illusion about complete equality in the communist society;

- Political consciousness, to praise the Soviet power, which has created the best society in the history of mankind;

- Identity consciousness, for Estonians to feel togetherness with the Soviet people and recognise the Soviet Union as their homeland;

- Historical consciousness, to be aware of all the significant issues related to the establishment, consolidation, and defence of the Soviet power – which explain the development of history towards communism.[ix]

In this respect education in internationalism was closely related to the concept of the cultural revolution. It was a long-term programme aimed at total reorganisation of intellectual life, which was to result in creating „highly-developed communists”, who are free from the bourgeois class position and wrong ideologies. In order to destroy the nations, in the first place their culture, language and historical consciousness had to be done away with. The most effective means to do so, were systematic repressions against the bearers of culture and demolition of the social structure. More specifically, the people were deemed to be the same as the state and ethnic structures had no place there. As a result, the fusion and assimilation of nations were promoted as progressive processes. But it was necessary to fight against such phenomena as nationalism, ethnic prejudices, selfishness, egotism, cosmopolitism etc. The same categories were used to judge culture.

By breaking national integrity and cultural traditions, a nation’s ability to resist assimilation was weakened. A nation survives only as long as its shared culture and national consciousness exists. The nation to be assimilated broke into two: those who became assimilated (or almost assimilated) and those who turned into „a closed-up group“ and against all odds retained their old cultural traditions. These two groups were in bitter conflict and paradoxically, an assimilated person very often turned out to be the worst chauvinist, russifier and destroyer of the culture.

A specific feature of the assimilation policy was that the repressive cultural revolution did not hit only the ethnic minorities but also Russians, and them even the most severely. In addition to the elites of the minority nations, the intellectual elites of the Russians were also liquidated, for they were the bearers of cultural and ethnic identity. Imperial Russia wanted to act as a melting pot where all the minorities would be integrated into the Russian cultural and language space, but the Soviet totalitarian regime aimed at destroying all cultures, including the Russian culture. Therefore, it is understandable why, for decades, the Soviet Union propagated cutting of people’s hereditary roots, mechanical mixing of ethnicities, resettlement, and mixed marriages. Thus, a mixed culture was introduced, the cultural roots were severed, and continuity lost, ending up in a surrogate culture. This was an empty cultural space, and it was then easy to introduce an ideological mass culture, which posed no questions but provided readymade answers.

The totalitarian regime could only exist, if its people did not ask questions and were unaware of the alternatives. The state took upon itself to think on behalf of the people, to protect and support them and in return demanded that the people were fully subordinated to that state. „The new human” was slow to evolve, but the breeding was not altogether resultless. The prototype of homo sovieticus that had appeared by the final years of the Soviet Union was still far from ideal, there was still a lot of room for development when it came to work ethics, moral standards and they did not display much interest in Soviet culture and propaganda, but the main components were there — adequate ethnic identity, independent cultural awareness and capability of thinking were lacking and they did not doubt the decisions of the Communist Party. This was an individual who had not evolved in the natural course of historical and cultural processes but as a result of official ideology determined by the regime.[x]

List of sources.

[i] For more details, please refer to: Cultural revolution in Russia, 1928–1931, edited by Sheila Fitzpatrick (Bloomington : Indiana University Press, 1984); Barbara Barnouin, Yu Changgen, Chinese foreign policy during the cultural revolution (London : Kegan Paul International, 1998).

[ii] For more details, please refer to: В. Алпатов, История одного мифа : Марр и марризм (Москва : Наука, 1991); В. Алпатов, 150 языков и политика 1917–2000 : социолингвистические проблемы СССР и постсоветского пространства (Москва : Крафт+ : ИВ РАН, 2000); Paul Ariste, „Akadeemik N. Marr – nõukogude keeleteaduse looja,” Looming, nr. 10 (1949): 1256; Georgi Serdjutšenko, N. J. Marri osa materialistliku keeleõpetuse arendamises (Tallinn : Eesti Riiklik Kirjastus, 1950).

[iii] РАПП, Российская ассоциация пролетарских писалтелей; РАПМ, Российская ассоциация пролетарских музыкантов); АХРР, Ассоциация художников революционной России; АХР, Ассоциация художников революции; РАПХ, Российская aссоциация пролетарских художников.

[iv] Aleksandr Jegolin, Kirjandusteaduse küsimusi J. V. Stalini keeleteadusalaste tööde valguses (Tallinn : Eesti Riiklik Kirjastus, 1952), 8–9, 29;

[v] Vt V. Lenin, „Kriitilisi märkmeid rahvusküsimuse kohta,” ), Rahvus- ja koloniaalküsimus (Tallinn: Eesti Riiklik Kirjastus), 118.

[vi] Jossif Stalin, Marksism ja rahvusküsimus (Tallinn : Eesti Riiklik Kirjastus, 1953), 17–23.

[vii] Viive Külaots, „Kultuurirevolutsiooni osast eesti sotsialistliku rahvuse kujunemisel,” Eesti sotsialistliku rahvuse kujunemisest (Tallinn : Eesti Raamat, 1970), 29–60; I. Ševtšuk, K. Põder, Rahvuslikud ja internatsionaalsed elemendid rahvuskultuurides (Tallinn : Eesti NSV ühing Teadus, 1978); Peet Lepik, „Nõukogude kultuur ja ideoloogia,” Eesti kultuur 1940. aastate teisel poolel = Estonian culture in the second half of the 1940s: Acta Universitas Scientiarum Socialium et Artis Educandi Tallinnensis = Tallinna Pedagoogikaülikooli Toimetised: Humaniora A19, toimetanud ja koostanud Kaalu Kirme, Maris Kirme (Tallinn : TPÜ, 2001), 9–16; Haljand Udam, „Totalitaarse võimu semiootilised praktikad,” Vikerkaar, nr. 10/11 (1998): 138–144.

[viii] Reet Kandimaa, „Rahvuslikust eseseteadvuse ideoloogilisest mõjutamisest 1970–80ndail aastail,” Eesti Kommunist, nr. 11 (1989): 36–37.

[ix] Anu Raudsepp, Ajaloo õpetamise korraldus Eesti NSV eesti õppekeelega üldhariduskoolides 1944–1985 (Tartu : Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus, 2005), 96.

[x] For more details, please refer to: Mart Nutt, „Homo soveticus’e sündroom,” Looming, nr 2 (1989): 221–225.