March Deportation. Arduous Journey to Siberia

Based on archival sources and memoirs, Aigi Rahi-Tamm, a historian, and Associate Professor of Archival Studies at the University of Tartu, describes the difficulties suffered on the way by the Estonian citizens who were forcibly deported to Siberia in March 1949. The March deportations were carried out based on the USSR Council of Ministers 1949 Decree No 390-138ss, pursuant to which 22,500 persons had to be deported from Estonia and a total of 87,000 from the three Baltic States together. They were labelled „kulaks“, „bandits“, „nationalists“ etc. and included the elderly and children.

The original article was published in the Proceedings of the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory 2, „„Priboi“ Files. Articles and Documents of the March 1949 Deportations“ (editors Meelis Saueauk, Meelis Maripuu, 2020). The book can be obtained from the University of Tartu Press online store or from regular bookstores.

According to the plan adopted by the Soviet Ministry of Internal Affairs on 24 February 1949, on the procedure and instructions for receiving, transporting, and settling a new contingent of deportees, the people taken from the Baltic States had to be resettled in the kolkhozes and sovkhozes of the Yakut ASSR, the Habarovsk and Krasnoyarsk Krais, and the Tomsk, Novosibirsk, Omsk, Irkutsk and Amur Oblasts.

By the beginning of March data had to be gathered to prove that the sites were ready to receive the deportees. Information also included weather conditions – whether and to what extent the beginning of spring, breakup of the winter ice on rivers, spring thaw etc. could hinder the settling of the deported persons in specific locations. One of the tasks was assistance in formation of the echelons.

The operatives who had prior experience in accompanying the trains and solving the problems that could occur during the journey were especially sought after. Similarly, the Soviet Ministry of Internal Affairs was looking for persons to be seconded to the locations to prepare for the arrival of the deportees and find them accommodation.

The echelons were to be equipped with medical staff, which the Soviet Ministry of Health had to provide[1]. Every echelon was assigned a convoy chief, and an echelon chief, with operative and economic deputies.

During the last days of March 1949, 19 special echelons carrying more than 20,000 people departed Estonia. Trains No 97301–97310 went via Narva, and No 97311–97319 via Pechory[2].

The echelons moved mostly at night, avoiding large cities, during daytime they were often parked on remote sidings. The people in the trains tried to figure out their whereabouts.

The echelons moved mostly at night, avoiding large cities, during daytime they were often parked on remote sidings. The people in the trains tried to figure out their whereabouts. Holes were made in the wooden walls of the carriages, to get some clue about the journey. Once they passed the Ural Mountains things became clearer – the vast plains and taigas of Siberia lay ahead. The three to four weeks on the road became a special phase in the lives of the deportees – trying to make sense of the situation both for themselves and others sharing their fate. On board the trains people could recover from the first shock to some extent.

The decision about deportation for life read out to the people when they were arrested did not explain the reasons or provide answers to the questions that gnawed at their souls. Grief and lack of knowledge caused both despair and anger.

The general mood was especially low in carriages with more elderly and sick people, and small children. As the journey progressed towards Siberia, deaths became more frequent, in particular among children and the elderly. While still travelling through Estonia, people tried leaving messages to their loved ones in railway stations. The guards collected many of the letters dropped out of the carriages, but a considerable number of the letters were found by good people and delivered.

As the echelons drew out of the stations people in many carriages started singing. When crossing the border, the Estonian national anthem, or some other tune close to the hearts of people, was sung, e.g., „Jää vabaks, Eesti meri“ (Stay Free, the Estonian Sea), „Mu isamaa armas“ (My Dear Fatherland) etc. The Poles who were deported in 1940, had been singing religious hymns with great passion during the whole journey and after that singing in trains was forbidden. [3].

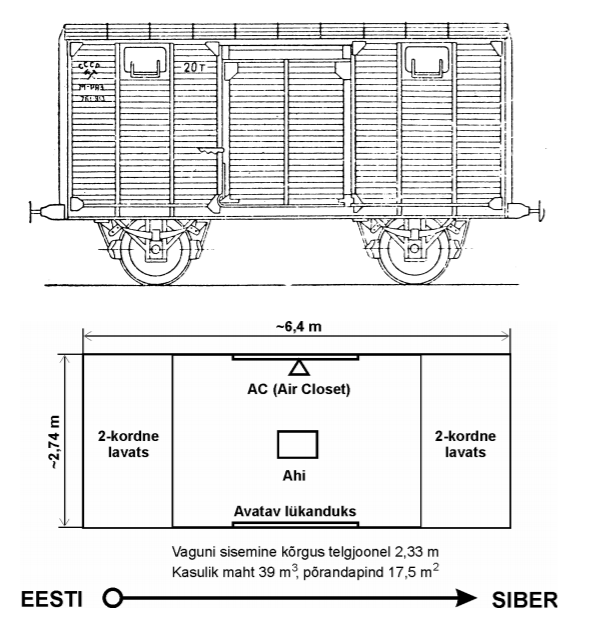

It depended on the mood of the guards, to what extent the prohibition was adhered to. The detainees were transported in two-axle or four-axle prison wagons, the wagon walls had sliding doors, the barred windows were close to the ceiling and people called them cattle wagons.

The echelons consisted of a combination of 25- and 60-ton wagons. Inside the wagons varied greatly. Usually there were wall-mounted bunks for sleeping, on rarer occasions plank beds, in some cases bunks by one wall and planks by the other. But there were also wagons with no bunks at all, and people had to huddle on top of their bags and bundles.

The echelons also had a few freight wagons to carry the belongings of the deportees and fuel for heating. Since the weather was cold, the wagons had to be heated. A small cast iron stove, named Burzhuika was placed in the middle or into the corner of the wagon. Lucky were those who had something to put into the oven. But in many cases the deportees had to obtain their own fuel. Being cold all the time made people listless, and the situation was made worse by not being able to wash themselves and by the spread of lice.

Answering nature’s call was another great worry. Usually there was a pail of water and another for excrements (latrine bucket). Another option was to cut a hole in the floor, to be used by the elderly, the sick and the children. „Sitting on the bucket“ was embarrassing and items of clothing were used to shelter such activity from others. People were not allowed to leave the wagons, when the trains were still in Estonia, the first stops were near Pechory and Pskov.

This brought along a new challenge – how can you do it, when all around you is nothing but a plain field, guards, men and women, your own kin, and strangers? Because of such psychological reasons many developed constipation that could lead to bleeding. At first people were allowed to leave the wagons for only about 20 minutes and they could not go further than five meters, lest they escape.

After the echelons had passed the Ural Mountains the stops became more frequent. People remember that there was a longer stop in some station once every 24 hours, to get hot soup from the station canteen or restaurant. There was a lot of variation in providing food to the deportees in the echelons, but according to the instructions[4] all special deportees had to be given two hot meals and a specified amount of bread per day and hot water twice a day.

The echelon chief was given 10 roubles per 24 hours for every person for food. It was strictly forbidden to hand out money instead of food, but there were cases when mothers with babies were given money to buy milk etc. At the beginning of the journey, people could eat what they had brought along, sharing the food with others, especially with those who were taken directly from the street and had had no chance of bringing anything along. The soup handed out during the journey was not only inedible, but also caused diarrhoea in most people, so it was wiser to avoid eating it altogether.

If possible, additional food was acquired from the locals, who were selling milk, vegetables, eggs, and other victuals in the railway stations. As the supplies were running low, the deportees had to make do with what was offered at the food distribution points. The echelon chief had to order the food 24 hours in advance by telegraph, and it was important to follow the agreed route to get the food. In every wagon one person was appointed head of the wagon, whose task was to get the food and hot water. Often such persons were mothers of small children, as the thinking was that they would not escape and leave their babies behind.

The knowledge of the Russian language was important. The duties of the wagon head included maintaining order and cleanliness in the wagon, keeping the list of deportees, and assisting the echelon chief in taking the roll call. The wagon head also had to notify the guards about persons who had been left behind during stops and any conflicts between the deportees.

The echelon chief had to contact the local MVD and militia in case of any problems, concerning, for example, the movement of the echelon, provision of fuel or food, taking the sick to the hospital, and the latter had the obligation to assist. Deportees who became ill during the journey were first taken to the isolation wagon and then transferred to the nearest hospital. After recovery, they were to continue their journey to the resettlement site.

Dangerous infectious diseases, like tuberculosis, scarlet fever etc. were not rare and people feared catching the diseases and vocally demanded the isolation of such patients.

Although the echelon teams included a physician and two nurses, the deportees do not remember seeing them too often, if at all. Family members and fellow deportees had to look after the sick. The guards did not display any interest in the condition of people, other than asking occasionally if anyone was sick. Dangerous infectious diseases, like tuberculosis, scarlet fever etc. were not rare and people feared catching the diseases and vocally demanded the isolation of such patients. But as this also meant being separated from family and friends, attempts were made to hide the diseases. Information about the number people who fell ill, died, or committed suicide varies.

According to the report of Captain Kovalenko, deputy head of the 3rd special department of the ESSR MVD from 30 May 1949, 45 people died under way, 62 were removed from the echelons due to disease, and 6 on the orders of the MGB.[5]

It is difficult to say whether these figures are correct or not. The dead had to be handed over to the railway militia, by filling out a special document to the effect. It is not known, what happened to the bodies or where they were buried.

Mostly people remember that the body was moved to the fuel wagon or taken somewhere out of sight under cover of darkness. Many who were seriously ill when taken from their homes died during the first weeks and months. A lot of children also died because of the harsh conditions.

„The Reials were the most unfortunate family in our wagon, Eedi, the son, had probably TB, the mother broke a leg when entering or exiting the wagon but she was such a patient person that the others learned about her accident only when we were leaving the train at the final destination; grandpa Reial must have had kidney disease, he died a day before we arrived, his body was taken out in some station and we never learned what became of it.“[6]

The main duty of the guards was to stop anyone from escaping. The deputy of the echelon chief in charge of operative matters was responsible for preventing and foiling any attempts to escape. In case of escape pursuit had to be organised. To avoid incidents data was gathered about „suspicious“ persons. It was supposed that there were more suspect individuals among singles than those who were deported as whole families. For this purpose, informers were to be recruited; according to instructions, there had to be at least two informers in each carriage. During the walks, distribution of food, fuel, etc., the sentiments of the deportees were to be investigated.

Individuals who tried to contact the guards, e.g., to send letters or obtain alcohol, were deemed suspicious. Persons inclined to escape had to be placed under reinforced guard.[7] Escapees who were caught had to be returned to the echelon, to demonstrate the futility of the attempts. Despite these measures, at least 12 deportees from Estonia were able to escape.

For example, Samuel Sooväli could escape from a railway station near Moscow, Ivo-Heiki Mahnke ran away somewhere in Central Russia. Upon their return to Estonia both men joined the organisation „Blue Legion of Tartu Youth“ and attacked (and wounded) the Chairman of the Executive Committee who had participated in the deportations. They were caught in the middle of June, charged under § 58-1a of the Penal Code of the Russian SFSR and sentenced to 25 years in the hard labour camp by decision of the Special Council. After release, Sooväli was deported to the Kormilovka Raion (district) in the Omsk Oblast.[8] Ivo-Heiki Mahnke was given a similar sentence of 25 years and was finally released from the prison camp in 1960.[9]

The echelon chief could caution or reprimand a troublemaker or prepare a report for the person to be prosecuted upon arrival in the final destination. Organisers of major disorders had to be removed from the echelon immediately and handed over to the local militia. The instructions required the guards to be strict, but not malicious with the deportees. People have different memories of the guards – there were those, whose behaviour was really gross, but also others who were friendlier and displayed compassion towards the deportees.

Aigi Rahi-Tamm (born 1965) has been Head of Archival Studies of the Institute of History and Archaeology at the University of Tartu since 2014 and Associate Professor of Archival Studies since 2021. She is member of the Commission on Examination of the Losses Inflicted on the Estonian Nation by Occupying Totalitarian Regimes. Rahi-Tamm has participated in many international projects and engaged in research in the Stanford University in the USA and University of Jena in Germany. She is the author of numerous publications in many scientific journals

Literature:

[1] Lietuvos gyventojų trėmimai sovietinės okupacinės valdžios dokumentuose 1940–1941, 1945–1953 metais sovietinė s okupacinė s valdžios dokumentuose: dokumentų rinkinys, atsakingasis redaktorius Antanas Tyla (Vilnius: Lietuvos Istorijos institutas, 1995), 484–485.

[2] According to the initial data in a report sent by the special operative of the USSR MVD, Major General Rogatin to the Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs of the USSR, Lieutenant General Ryasnoy in Moscow on 31 March 1949, 20,535 persons had been loaded into 1,057 carriages, Department of the Estonian State Archives (hereinafter: RA ERAF).17SM.4.100, 263.

[3] Репрессии против поляков и польских граждан, сост. А. Э. Гурьянов, Исторические сборники «Мемориала» 1 (Москва: Звенья, 1997), 141.

[4] Here and below reference to the instructions shall be taken to mean the Regulations on Special Resettlement, State Archives of the Russian Federation (Государственный архив Российской Федерации (hereinafter: ГАРФ) Р-9479.1.448, 234–312.

[5] RA ERAF.17SM.4.101, 330.

[6] In 1998 the Estonian National Museum (ERM) sent its correspondents two questionnaires about deportations (No 200 and No 201), the responses can be found in the ERM archives (ERM KV 867-883). This paper uses the answers the correspondents gave in those questionnaires. ERM KV, Loreida Sims. Jakob Reial died on 27 April 1949, please see: „Küüditamine Eestist Venemaale. Märtsiküüditamine 1949, 2. osa“ (Deportations from Estonia to Russia. March 1949 Deportation, Part 2), compiled by Leo Õispuu (Tallinn: Eesti Represseeritute Registri Büroo (Estonian Repressed Persons’ Records Bureau), 1999), 507.

[7] RA ERAF.17/1.1.139, 46. The whole document was published in the cultural journal Akadeemia, No 5 (1999), 1058.

[8] MGB Information Bulletin, 11.–20.06.1949, RA ERAF.131.1.159, 182–191; In: „Saatusekaaslased: Eesti noored vabadusvõitluses 1944–1954“ (Fellow Sufferers. The Freedom Fight of Estonian Youth 1944-1954), compiled by Udo Josia (Tartu, Tallinn: Endiste Õpilasvabadusvõitlejate Liit (Union of Former Student Freedom Fighters), 2004), 58.

[9] Eesti kommunismiohvrid 1940–1991 (Estonia’s Victims of Communism 1940-1991). Elektrooniline memoriaal (The Electronic Memorial), www.memoriaal.ee (30.03.2019).