Katyn massacre: how the truth prevailed

13 April has been declared a day of remembrance for the victims of the Katyn massacre by the Polish Parliament. The Katyn Massacre is one of the most atrocious political crimes committed by the communist Soviet Union - about 22 000 Polish prisoners of war and political prisoners were killed. Katyn is a story of covering up the truth and bringing it to light through difficulties. Dr. Krzysztof Persak of the Polish Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Political Studies writes that we know quite a lot about the circumstances of the Katyn massacre today, however, the discussion is yet to cease.

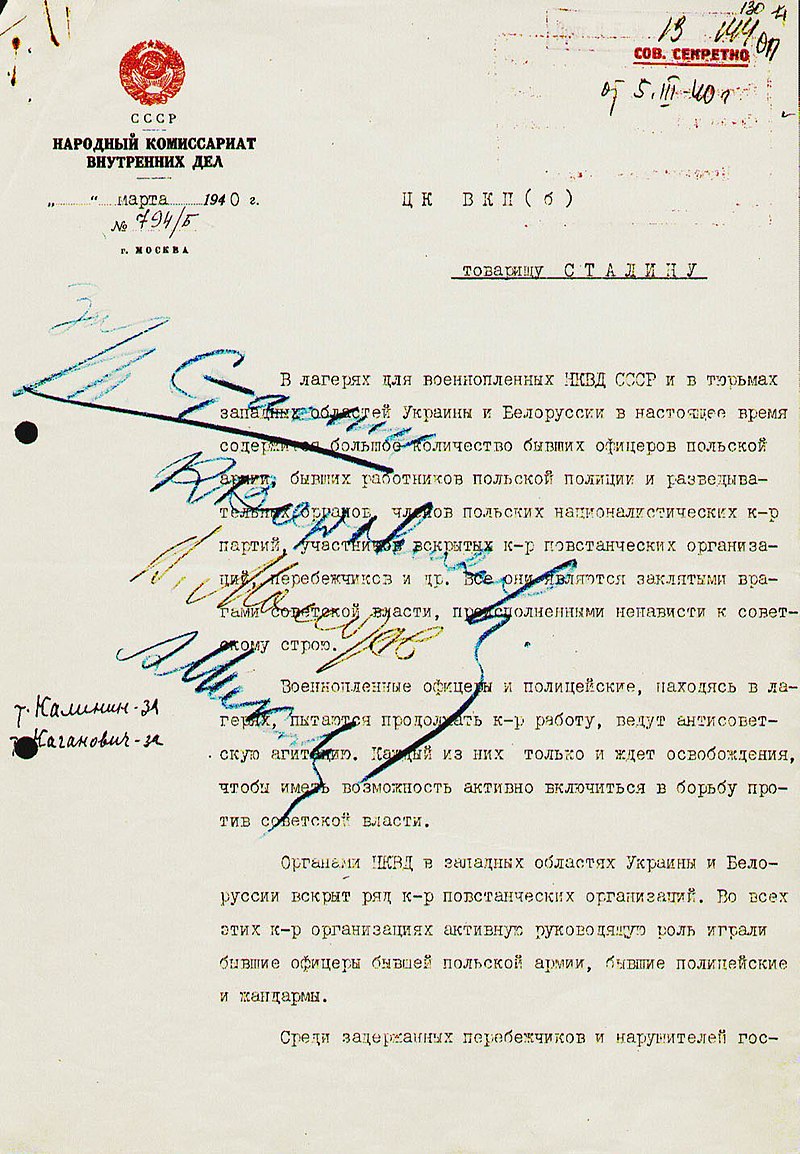

The name of the Russian village of Katyn, where in 1943 the Germans discovered burial pits of thousands of Polish Army officers murdered by the NKVD, became synonymous with an unprecedented Soviet war crime and crime against humanity. A total of almost 22,000 Polish prisoners of war and political prisoners, who were executed in the spring of 1940 on the basis of the decision of the leadership of the Soviet communist party of 5 March 1940, fell victim to this crime. The Katyn massacre casts a dark shadow on Polish-Russian relations until today.

Two weeks after the German aggression against Poland, the Red Army struck from the east, occupying half of the pre-war Polish territory. 240 000 Polish soldiers, policemen, and border guards got into Soviet captivity. On the occupied territory, special NKVD operational groups started massive arrests of Polish officials, workers of the judiciary, civic and political activists, bourgeoisie and landowners as well as those army officers and policemen who had not been taken prisoner before. With time the NKVD detained growing numbers of members of Polish underground organisations.

The majority of rank-and-file soldiers and non-commissioned officers were released after a few weeks, and officers were concentrated in two prisoners of war (POW) camps – in Starobelsk in eastern Ukraine and in Kozelsk south-west of Moscow. As of 1 April 1940, there were 3894 and 4599 prisoners respectively in these camps, with 13 generals and 279 colonels and lieutenants-colonels. A third of the prisoners were career officers with the rest being reserve officers, usually representing various intellectual professions. The third camp in Ostashkov in northern Russia was designed for policemen, gendarmes, prison guards and intelligence agents. In the beginning of April 1940, there were 6364 POWs in the camp.

All three camps were organised in former Orthodox monasteries. Although their 14,857 detainees were referred to as prisoners of war, the camps were supervised by the political police, not the Red Army. NKVD agents specially sent from Moscow interrogated the POWs for several weeks in order to determine their pre-war activity, political views and attitude to the Soviet regime. The prisoners were also exposed to communist propaganda. But the efforts to politically re-educate them turned out unsuccessful, and the NKVD reported about their patriotism, eagerness to fight for Poland’s independence, and refusal to collaborate.

The decision to exterminate all Polish POWs was made quite suddenly at the turn of February and March 1940, and the question of its motives is still unresolved. In February, an operation to “clear out” the POW camps was still being prepared possibly in connection with the expected influx of prisoners from the Soviet-Finnish war, but no one envisaged killing the Poles then. The policemen were to be sentenced to labour camp terms, and the army officers were to be partially released or also brought to justice for “counterrevolutionary activity”.

However, on 5 March 1940, the Politburo of the VKP(b) CC accepted Lavrentiy Beria’s proposal to shoot all Polish POWs. In his memorandum to Stalin, Beria presented them as a threat to Soviet security: “They are all sworn enemies of Soviet power, filled with hatred for the Soviet system of government. (...) Each one of them is just waiting to be released in order to be able to enter actively into the battle against Soviet power”. In the realities of the Soviet system it seems obvious that Beria could not have put forward such a proposal without Stalin’s prior approval, and most likely without his suggestion.

In the same memo, Beria proposed to shoot also 11,000 Polish political prisoners held in jails in western Belarus and western Ukraine, more than half of them being policemen and military personnel. The cases of POWs and prisoners sentenced to death were to be dealt with in absentia by a special NKVD troika chaired by Beria’s deputy, Vsevolod Merkulov.

The murderous operation, carefully planned, was carried out from April through May 1940. Groups of 200-300 prisoners were dispatched from the camps to be executed at three selected NKVD provincial headquarters on the basis of lists received from Moscow. POWs were given the impression that they were to be transferred to other camps or released so they offered no resistance.

6311 prisoners from Ostashkov camp were shot in the back of the head in Tver and buried in nearby Mednoe, 3820 officers from Starobelsk were killed in Kharkiv and buried in Piatikhatki park on the outskirts of the city, and 4415 prisoners from Kozelsk were killed either in Smolensk or on the edges of the burial pits in Katyn, 15 km away. All three burial sites had already been secret cemeteries of the victims of the Great Purge of 1937-1938. Later, recreational areas of NKVD/KGB were established there.

According to current research, a total of 14,546 POWs were killed. Only about 400 prisoners escaped execution for various reasons, including prospective collaborators or – to the contrary – officers whom the Soviet intelligence services wanted to investigate further.

Incomparably less is known about the fate of the executed political prisoners. According to the 1959 report by the head of the KGB Aleksandr Shelepin, 7305 prisoners were finally shot. It was only in 1994 that the Ukrainian authorities released a list of 3435 prisoners (including 50 women) shot in western Ukraine. Executions took place in Kiev (with the burial place in Bykivnia) and probably in Kharkiv and Kherson.

The list of those who were executed includes policemen, military personnel, members of the social elite, and political activists – not only ethnic Poles: about 20 percent of the names on the “Ukrainian list” sound like Ukrainian or Jewish. From the above numbers one can infer that in western Belarus 3870 political prisoners were shot based on the 5 March 1940 Politburo resolution (probably in Minsk with the burial place in Kuropaty). We still know nothing about them.

Family members of the shot POWs and political prisoners were also persecuted according to the Soviet principle of collective responsibility. On 13 April 1940, 61,000 of them were forcibly resettled to northern Kazakhstan, where many died of malnutrition and disease.

On 13 April 1943, the German radio broadcast a message about mass graves found in Katyn. Discovering the crime committed by one of the Allied forces was a gift to Nazi propaganda. The Germans organised a mass exhumation with the participation of international experts from German-occupied or satellite countries. A total of 4243 corpses were excavated, 2730 of which were recognised as Kozelsk prisoners, testifying to the Soviet crime.

The Polish government in exile found itself in a difficult situation. The Soviet government, which from the onset shifted the responsibility for the crime to Germany, used the Polish request to the International Red Cross to conduct an independent investigation as a pretext to sever diplomatic relations with Poland, and accused the Polish government of multiplying Goebbels’ propaganda.

After recapturing Smolensk the Soviets appointed their own commission chaired by the Red Army chief surgeon, Nikolai Burdenko, which “proved” the German responsibility for the Katyn massacre. Ironically, its work was supervised by Merkulov, who had led the Katyn operation three years earlier. On the other hand, the Soviet authorities did not succeed to attribute the responsibility for the Katyn massacre to Germany during the Nuremberg trial. In the post-war years, for the sake of disinformation, the Soviets popularised a memorial site at Khatyn (Хатынь) in Belarus, where the SS annihilated a village in 1943, a topographic name that sounded similarly to Katyn (Катынь).

The Katyn massacre became a taboo in post-war Poland. The state censorship suppressed all information on it, people who had been involved in the German investigation were persecuted and the families of the victims could not cultivate the memory of their beloved ones.

New information about the Katyn crime came to light during the perestroika and glasnost period at the turn of the 1980s and 1990s. Russian journalists discovered burial places of victims of Stalinist repressions at Piatikhatki, Mednoe and Bykivnia, while historians reached some NKVD archival documentation. Under this pressure, the USSR authorities were compelled to admit the Soviet responsibility for the Katyn crime (13 April 1990) and released the lists of the executed POWs to the Polish government. Two years later, on 14 October 1992, a special envoy of the President of Russia Boris Yeltsin handed over to the President of Poland Lech Wałęsa the documents of the Soviet Politburo from 1940, revealing the full scale of the Katyn crime.

In the 1990s Polish experts carried out exhumations in Piatikhatki, Mednoe and Katyn, and in 2000 Polish war cemeteries were opened there. The fourth cemetery of the victims of the Katyn crime was opened in Bikivnia in 2012. The burial place of prisoners who may have been shot in Kherson is still unknown.

Despite the official recognition of responsibility for the Katyn crime by the authorities of the USSR and the Russian Federation, negationist publications have been increasingly frequent in Russia in recent years.

Sources:

Katyn: A Crime Without Punishment, eds. Anna M. Cienciala, Natalia S. Lebedeva, Wojciech Materski, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

Katyń. Dokumenty Zbrodni, vol. 1-4, eds. Wojciech Materski et al., Warszawa: NDAP, 1995-2006.

Sanford, George: Katyn and the Soviet Massacre of 1940: Truth, Justice and Memory, London: Routledge, 2005.

Катынь. Март 1940 г. — сентябрь 2000 г. Расстрел. Судьбы живых. Эхо Катыни. Документы, отв. составитель Н. С. Лебедева, Москва 2001.

Катынь. Пленники необъявленной войны, отв. составитель Н. С. Лебедева, Москва 1999.

Лебедева, Наталья С.: Катынь. Преступление против человечества, Москва 1994.