Incredible courage: bringing the Great Chinese Famine to light

For decades, the world was unaware of the details surrounding the Great Chinese Famine, a disaster brought about during the rule of communist leader Mao Zedong. A brave Chinese journalist Yang Jisheng conducted a risky research while working in China’s state news agency, breaking down a wall of silence. We now know that due to the fanaticism and incompetence of China’s Communist Party, up to 40 million people died of hunger. The disaster is the greatest man-made famine in human history. The author of the story is Richard McGregor and it was first published in Financial Times.

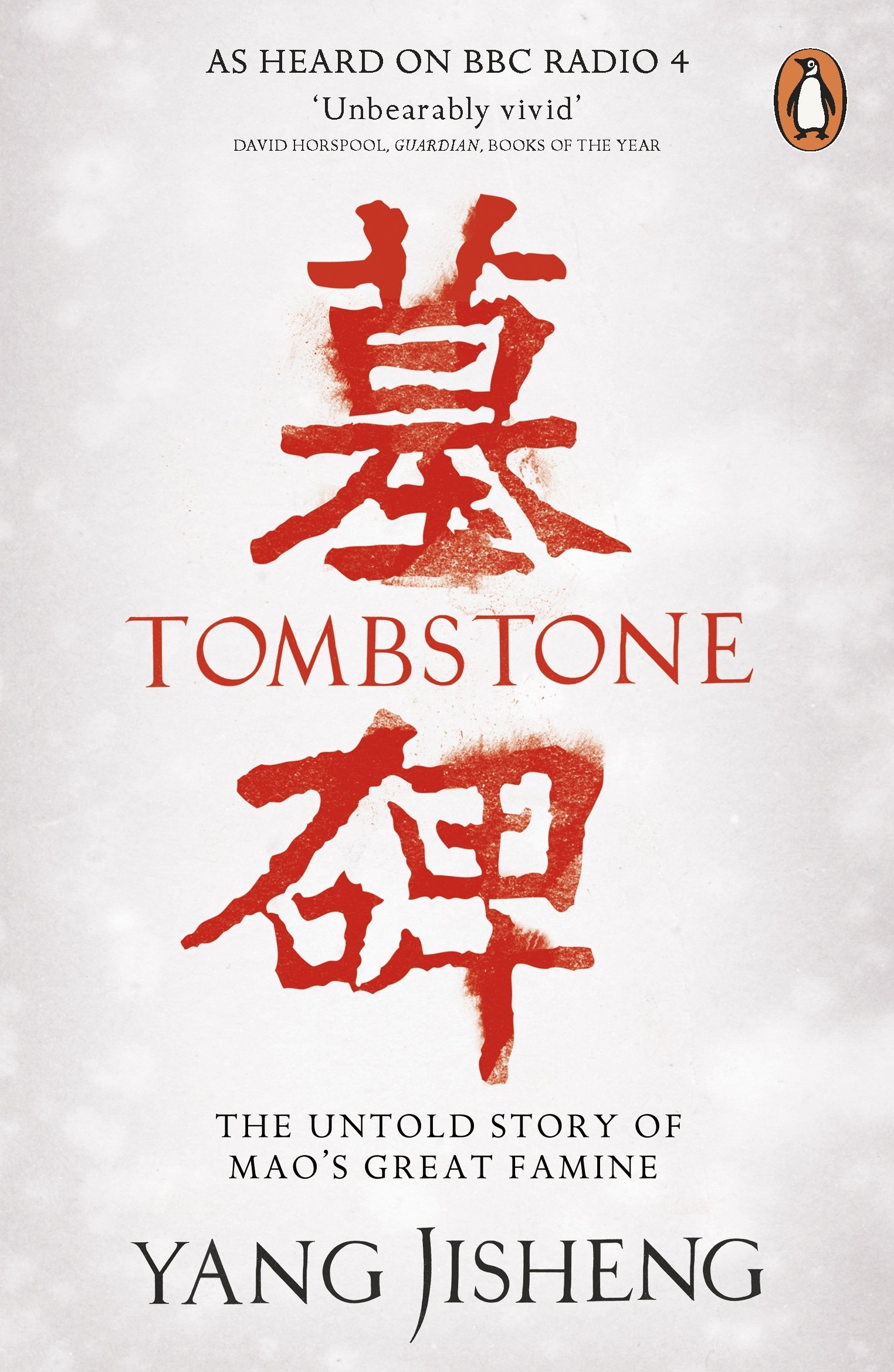

When the first editions of Tombstone landed in Hong Kong bookshops in mid-2008, they had to be stacked like old-fashioned telephone directories, one on top of the other. The book’s intimidating physical presence matched the gravity of its content.

Tombstone took its author, Yang Jisheng, nearly two decades of painstaking research to compile. In two volumes, it gives a minutely chronicled and irrefutable account of the death by starvation of 35-40 million Chinese between 1958 and 1961. It details a tragedy the ruling Communist party has long sought to cover over.

Yang’s epic work was confirmation of what any student of world affairs outside China already knew – that Mao Zedong’s utopian plans to accelerate the establishment of what he called “true Communism” had produced the worst man-made famine in recorded history. Almost as remarkable as the book itself was how Yang, a journalist with Xinhua, the official state news agency, had managed to research and write it.

For most of his career, Yang, 69, had faithfully done what Xinhua reporters do: write stories, cleared through the propaganda system, for the public news wire. Backstage, he performed a second, covert function required of senior Xinhua journalists – he provided secret internal reports to the party itself. Yang had not pulled his punches in these on-the-ground dispatches, vital to Beijing’s efforts to monitor officials outside the capital.

A number of his reports, about the military’s abuse of its powers, economic decline and official corruption, landed on the desks of senior leaders in Beijing, to the consternation of the party bosses in the regions where he was based. It was not until 1989 that Yang, angry and disillusioned over the violent military crackdown around Tiananmen Square, set off on a new path.

Instead of spying on the regions for Beijing, Yang launched a mission against his masters. Using the privileges afforded a senior Xinhua journalist, Yang was able to penetrate state archives around the country and uncover the most complete picture of the great famine that any researcher, foreign or local, has ever managed. The book he wrote was the consummate inside job, the product of a lengthy, clandestine co-operation with fellow party members determined to expose the lies told about the famine in China for decades.

Yang was helped by scores of collaborators within the system – demographers who had toiled quietly for years in government agencies to compile an accurate picture of the loss of life; local officials who had kept the ghoulish records of the event in their districts; the keepers of provincial archives who were happy to open their doors, with a nod and a wink, to a trusted comrade pretending to research the history of China’s grain production; and fellow journalists from Xinhua willing to use their contacts so the true story of the disaster could be told.

One of the most horrifying tales uncovered by Yang in the course of his research came from Xinyang, a small city in Henan province, where the famine was at its worst. When he visited, Yang was not directed to the official archives as he’d expected, but instead sent to meet Yu Dehong, a retired cadre from the local waterworks bureau. In their own quiet way, the Xinyang officials might have been giving Yang a helping hand.

Yu was what you might call the local history crank – except the stories he nagged people about did not concern municipal landmarks or the arrival of the city’s first steam train. As the political secretary to the Xinyang mayor in the late 1950s, Yu was an eyewitness to a mini-Holocaust in his hometown, its surrounding villages and even his own family.

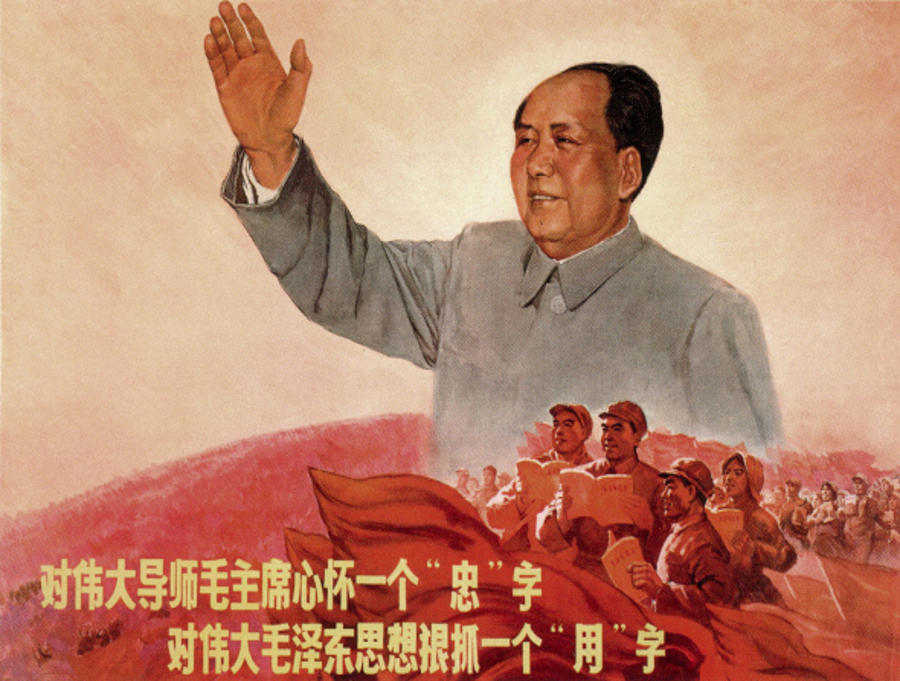

Mao had ordered Chinese farms to be collectivised in the late 1950s and forced many peasants who had once productively grown grain to put their energies into building crude backyard blast furnaces instead. As part of this “Great Leap Forward”, Mao’s acolytes predicted that food production would be doubled, even tripled in a few years and that steel production would soon surpass output in advanced western countries.

The new rural communes began reporting whopping, fake harvests to meet Mao’s demand for record grain output. When the government took its share of the grain based on the exaggerated figures, little was left for ordinary people to eat.

According to the most conservative calculations, one million people out of a population of eight million in Xinyang died between 1958 and 1961. Yu was often gently advised to drop the issue in the years afterwards. Instead, he wrote a detailed account in his own name and submitted it to the local party secretary. “Some people asked me, ‘Haven’t you committed enough mistakes?’” he said. “But if the official history won’t include this material, then my private history will. I have the materials to back me up.”

Xinyang was generally blessed with good harvests, unlike much of Henan, known as the “land of beggars” for its history of impoverishment and famines. But any advantage the city had was undermined by the officials who ruled over it. At the time, Henan and Xinyang were overseen by radical leftists fanatically devoted to Mao who viewed the grain harvest solely through the prism of violent class struggle.

Yu remembers vividly a series of surreal meetings in 1959, when the 18 counties in Xinyang city reported their harvest for the year. After a furious debate in which each county reported wildly exaggerated figures, they settled on a figure about three to four times the real size of the harvest. The distortion was more than enough to set in train the disaster that followed. It was not long before mass starvation began to grip the city and surrounding areas.

As winter turned to spring in the early months of 1960, a thick smell of death began to rise out of the landscape. Yu remembers the change of season clearly. Walking around the semi-rural enclave, he saw thousands of corpses strewn alongside the roads and in the fields.

During the winter, the bodies had hardened and set in the cramped, bent shapes in which people had died. They looked like they had been taken out of a freezer and then randomly scattered across the landscape. Some of the corpses were clothed, but the garments had been ripped from others, and flesh was missing from their buttocks and legs. In the first days of spring, the corpses began to thaw, emitting a sickly smell that permeated the everyday life of a shell-shocked local citizenry.

The surviving residents protested later that they had been too short-handed and exhausted to give the dead the dignity of a burial. They blamed the disfigured corpses on hungry dogs, whose eyes, according to rumours which swept the area, had turned red after gnawing at human flesh. “That is not true,” said Yu. “All the dogs had already been eaten by humans. How could there be dogs left at the time?” The corpses hadn’t been eaten by ravenous animals. They had been cannibalised by local residents. Many people in Xinyang over that winter, and the two that followed, owed their survival to consuming dead members of their families, or stray corpses they could get their hands on.

Stories like Yu’s shocked Yang. “I did not foresee this level of cruelty,” he said. “There was cannibalism in the ancient time in famines. People used to talk about ‘exchanging children to eat’, because they could not bear to eat their own children. But this was much worse.”

It goes without saying that Tombstone could not be released in China. No publisher dared touch it, even though it sold briskly in Hong Kong. In Wuhan, a large city in central China, the office of the Committee of Comprehensive Management of Social Order put Tombstone on a list of “obscene, pornographic, violent and unhealthy books for children”, to be confiscated on sight. Otherwise, the party killed Tombstone with silence, banning its mention in the media but refraining from any attention-grabbing attacks on the book itself.

To understand the force that stymied attention for Yang’s book is to understand the battle he fought to report and write it in the first place. The Central Propaganda Department is the party’s overarching enforcer in China’s history wars. Its sentries stand guard at all the key points of the debate: in schools, to oversee textbooks; in think-tanks and universities, to monitor academic output; with the United Front department, to prepare what it calls “historically correct” materials for compatriots in Hong Kong and Taiwan; and throughout the media in all its forms, to scrutinise the output of everyone from journalists to film directors. Like all large party offices in the capital, the propaganda department has no listed phone number and no sign outside its sprawling headquarters. The instructions it issues to the media are secret.

The propaganda department does not underestimate the gravity of its task. Nothing less than national security is at stake. “In China, the head of the Central Propaganda Department is like the Secretary of Defence in the United States and the Minister of Agriculture in the former Soviet Union,” said Liu Zhongde, a deputy-director of the department for eight years from 1990. “The manner by which he brings leadership will affect whether the nation can maintain stability.”

By the early 1990s, Yang had become a roving economics correspondent for Xinhua, travelling around the country. He had also resolved to write and put his name to the stories the party had long suppressed – about the 1989 crackdown; political infighting among top leaders; and most importantly, the story of the famine. The first job would prove perfect cover for the second.

Yang’s political epiphany acquired a personal dimension after an interview with the long-time governor of Hubei. The governor told Yang that the great famine killed hundreds of thousands of people in Yang’s home province. The journalist began to rethink his own father’s death in 1959.

Yang had always remembered clearly the moment he found out his father was dying: he was a teenager at the time, a high-school student and living on a farm collective. He was also propaganda officer for the local branch of the Communist Youth League. An enthusiastic supporter of Mao, Yang was in the middle of writing a wall poster to promote the Three Red Flags campaign, glorifying the Great Leap Forward and the collectives, when a classmate burst into the room. “Your father is not going to make it,” the boy said.

Yang later blamed himself for not going home earlier, to dig for wild vegetables to feed the family. At the time, he did not think to blame Mao or the Communist party. It was an individual case, something to be handled within the family. Thirty years later, he developed a different perspective.

On and off during the next decade, Yang locked himself in provincial archives and pored over their records – population figures, grain production, weather digests, personnel movements and anything else he could get his hands on. Researching the great famine was the largest and riskiest project he had undertaken.

Pretending to be investigating rural issues and grain production, Yang was able to gain access to documents which had been locked away for decades. If his status as a senior Xinhua reporter wasn’t enough to get into the archives, he used the relationships his colleagues had built up with the provincial authorities. “My colleagues knew what I was doing,” he said. “They secretly supported me.”

In Gansu, in western China, a former Xinhua branch head well-known for his leftist views backed Yang and handed over materials. In Sichuan, China’s populous breadbasket, another ageing journalist did the same.

Of course, his ruse did not work every time. In Guizhou, one of China’s poorest provinces, Yang almost came undone. His colleagues took him to the provincial party compound to seek permission to access the archives. The nervous section head consulted the head of the archives, who referred the request to the deputy of the provincial party secretariat. He referred the request upwards to his boss, who then decided to consult Beijing.

A query to the central government could have easily exposed the research as a sham. “We would have been finished,” Yang said. On hearing about the request to Beijing, Yang coolly excused himself, saying he would come back another time. Tombstone, as a result, has no detailed chapter on Guizhou.

Yang worried constantly that he would be caught and his colleagues punished. “I felt like a person going deep into a mountain to seek treasure, all alone and surrounded by tigers and other beasts,” he says. “It is very dangerous, as using those materials is prohibited.”

Even the final nationwide death toll, a figure known in the west for more than two decades, was a revelation. To calculate the number, Yang had the confidential figures he had gained in the provincial archives. But he also called on another insider, a Chinese demographer who had for years been quietly gathering material about the impact of the famine.

Wang Weizhi returned from studying demography in the Soviet Union in 1959, the first year of the famine, and was employed by the Public Security Bureau, or police, where he worked for the next three decades. The job was to give him a unique vantage point to track the famine’s impact. China conducted just three censuses in the first three and half decades of Communist rule – in 1953, 1964 and 1982. The police, by comparison, compiled household registration data from around the country and updated it twice a year. Wang, in theory, had access to fresh population figures submitted directly to the centre from each county in the country.

Wang got his first inkling of the on-the-ground impact of the famine in 1962, when he was sent to Fengyang, in Anhui, an area that suffered a death toll on a par with Xinyang. The team was not dispatched to investigate the reports of starvation which had been reaching Beijing in the previous two years.

That would have been too politically sensitive. They were sent to find out why there had been such a spike in the birth rate that year. The villagers rather sardonically told the visitors from Beijing they should expect another birth spurt in 1963. The reasons weren’t difficult to fathom. The elderly and the young had been wiped out in the famine. “The oldest person left in the area was 43 and the youngest was seven,” said Wang.

Wang struggled for years to get his hands on a full set of state statistics from within his own workplace. During the Cultural Revolution, access to the numbers recorded during the famine was restricted. Anything before 1958 was easy. Anything later was difficult. “At the time, the figures were very sensitive, and very few people were allowed to have them,” Wang said. “Only the top five people in Shandong, for example, could see the Public Security Bureau figures: the party secretary and the governor and their deputies, and the police chief.” When the political climate improved in the late 1970s, Wang quietly began to collect materials. But it wasn’t until Yang came knocking on his door in the 1990s that he put forward his own estimate of the death toll for publication: 35 million.

In person, Wang seems very much a bloodless functionary, approaching the tragedy as a professional demographer rather than someone with a political axe to grind. He sticks strictly to the numbers, telling the story through the tables of figures in an old government population book that sits in the corner of his office at home, covered in thick dust. Look here, he says, brushing the dust off and stabbing his finger at a column of figures showing the population of one province dropping by three million.

He shrugged when I asked what the reaction had been in China in the 1980s when the real death toll had started to leak out. “Because it was so long ago, people were rather indifferent,” he replied. Wang’s professionalism made him invaluable to Yang. In a country where little is untainted by politics, Wang sticks simply to the facts. He said he was happy to assist Yang. “For me, these are the facts and if someone wants to investigate, I will give them the facts.”

To this day, the Chinese government has never said how many people it thinks died, although it commissioned a study in the mid-1980s for internal circulation. The academic who prepared that study had spent most of his life as a lecturer in automated production systems in Xian before studying demography for barely a year in India. He came up with a figure of 17 million premature deaths.

The study has been widely dismissed because it looked mainly at recorded deaths. “Half of the excess deaths did not get recorded at the time. People were focusing on survival, not statistics,” said Judith Banister, a US demographer. Meanwhile the study’s author, Jiang Zhenghua, was richly rewarded for his work and was promoted eventually to become vice-chairman of the National People’s Congress.

Yang had steeled himself for a backlash from the authorities in the wake of Tombstone. He was certainly vulnerable. He still lived with his wife in a Beijing apartment provided by Xinhua for his retirement and banks his government pension cheque every month. But so far, nothing has happened.

His collaborators remain similarly unmolested by the party. “The authorities are not as stupid as they used to be,” said Yang. “If this happened in the past, I would be a dead man, and my family would have been destroyed. But here I am, still writing books and giving talks. The fact that I have not been sent to prison in itself indicates there have been some changes.”

The last time I spoke with Yang Jisheng about Tombstone, he summed up China and the party’s progress with words that stuck in my head. “The system is decaying and the system is evolving,” he said. “It is decaying while it is evolving. It is not clear what side might come out on top in the end.”