The Fall of Romanian Communism. PART I: the political and economic background

The Romanian revolution was the last and the bloodiest of all the revolutions that broke out in Eastern Europe. Mihai Dragnea highlights the main contributing factors that preceded and led up to the fall of one of the most brutal dictators, Ceausescu's regime. In the first part of the article, the author argues that until the revolution, the regime was so harsh that no liberalising movements could ever develop within the society, and describes Ceausescu's unrealistic economic goals, which later brought misery to Romanian people.

The second part, which will be published later, further explains the negative consequences of the economic policy and tells how and why Ceausescu’s regime collapsed.

While communist regimes throughout Central Europe, Eastern Europe, and the Balkans had similar historical foundations, they collapsed in different fashions. In this sense, we can place countries in each of the aforementioned areas into three different categories.

The first category includes Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia, where communism was toppled without violence or human casualties. The second category includes the German Democratic Republic and Bulgaria, where violence was limited. The last category concerns Romania, where the collapse of communism resulted in the use of violence and civilian casualties.

It must be noted that the violence that took place in Romania was carried out by regime forces and not by demonstrators. According to official statistics, 1,142 people died, 3,138 were wounded, and 760 were arrested by Ceaușescu’s forces. There is no doubt that Ceaușescu’s regime left a bloody record. The case of the former Yugoslavia, where the bloodiest collapse of Communism occurred, is a special case with many other implications.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Ceausescu's Regime

The main weakness of Ceausescu's regime was that it never made the transition from totalitarianism to post-totalitarianism, a process that took place in the German Democratic Republic, Czechoslovakia, and even in Bulgaria to some extent. Political power in both the party and the country belonged exclusively to the Ceaușescu family and the Securitate (Department of State Security – DSS). The members of the party leadership were mere puppets who approved the increasingly delusional decisions of the ruling couple.

The dictatorial character of Ceaușescu’s leadership and Romania’s antagonistic relationship with the Soviet Union, which led to self-isolation from Moscow, had impending implications for the organisation and ideological content of the opposition.

The changes initiated by Mikhail Gorbachev in the Soviet Union and the reforms in other Eastern European states were denounced as a kind of “right-wing deviation” from socialism and a betrayal of its interests at the national level. Therefore, the opposition within the party-state apparatus was not only clandestine but also conspiratorial and ideologically undeveloped, focusing primarily on replacing the leader and only secondarily on the need to reform the system.

In the final twelve years of the regime, dissent in Romania consisted mainly of a number of isolated gestures by brave individuals, who refused the benefits of the party and dared to openly criticize the ruling couple and the party. Until the Revolution of 1989, there were no organized dissident movements coming from society itself. This can be explained by the fact that the actions of protest, either individually or in small groups of people, against the regime received exemplary punishment by public convictions that were decided by the Military Courts.

However, Ceaușescu's methodology to suppress dissents was based on coercion rather than punishment, as it was used by his predecessor, Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, to prevent any attempts to criticize the regime.

British historian Dennis Deletant emphasizes that the DSS, Romania’s secret police agency, was three times smaller than the Stasi (East German Ministry of State Security) in the GDR. This made the DSS brutally efficient, and it was considered one of the most developed intelligence services in the entire Soviet bloc.

After 1977, the DSS was reorganized with the help of high-level computer technology imported from the United States in the early 1970’s. This measure led to much better nationwide cooperation in preventing the coagulation of collective protests.

Therefore, the most active opposition was maintained by the Romanians who were members of the country’s diaspora. As Ceaușescu became increasingly discredited in the West, the opposition was supported by various international organizations, such as the OSCE, and media channels, such as Radio Free Europe, which was funded by the Central Intelligence Agency until 1972.

Economic Issues

The communist regime in Romania faced social and economic problems, which begun to slowly be felt in the late 1970’s. These issues were included in the rhetoric of public criticism of the regime used by dissidents, who became more active after 1980.

In addition to protests, a collective protest letter was also drawn up within the party and signed by six communist veterans who had been marginalized by the ruling couple. This letter had a limited impact on the wider public in Romania but had an echo abroad that was incomparably greater than that of the letters signed by critical intellectuals.

Western support for Romanian dissidents was considered foreign intervention by the country's internal affairs office and was treated as such, with the risk of deteriorating diplomatic relations. This scenario seemed even more suspicious to Ceaușescu, as many of the dissidents were either of Hungarian origin or non-Orthodox.

The illegal flight of many Romanians to Western countries and the precarious economic situation amid loans from the International Monetary Fund became a point of obsession for the regime. However, by the time it managed to pay its foreign debts in early 1989, Romania was already isolated internationally after having been condemned for human rights violations by not only Western countries, but also Hungary and the Soviet Union.

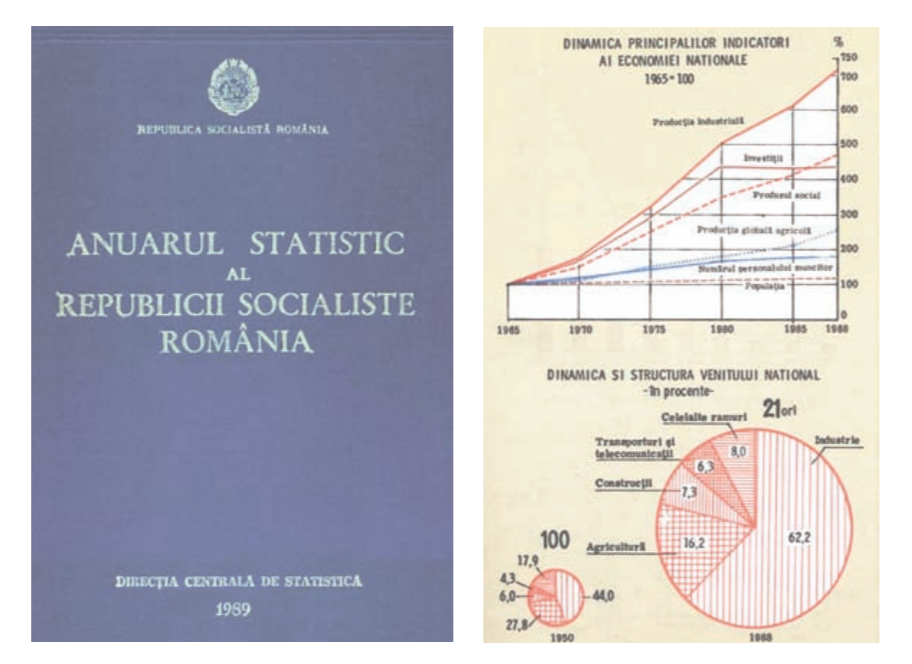

In regard to the evolution of the Romanian economy in the period of 1950-1989, it is important to note that the statistical data contained in the Romanian Statistical Yearbook (Anuarul Statistic al României) are relatively unclear. The official numbers are inflated, and this is largely due to the party's propagandistic character.

However, the most conclusive economic information comes from the 1990 Statistical Yearbook of Romania, which contains data from over 39 years, as well as new chapters and indicators that had not yet been published at that time.

The statistics published before 1989 in Romania should be considered less credible, as well as the data provided by various international bodies. Following the Soviet model, Romanian economic development had taken place on the basis of five-year plans since the early 1950’s.

More precisely, the economy was focused on industrial development through which at least in the party's view, a series of stages were pursued: the transformation of socialist Romania into an industrial-agrarian state, the elimination of economic development gaps at regional and local levels, the equalization of the economic and social levels of development between rural and urban environments, the creation of a modern structure of the economy at territorial levels, in which industry had a central role, and the rational use of resources available in each area and territorial unit, in accordance with national and regional needs.

The country’s production was based on heavy industry, which operated at the cost of deep sectoral imbalances and proved to be detrimental to public consumption. According to the 1990 Statistical Yearbook of Romania, the national income used for the consumption (consumer fund) and accumulation fund, in the period from 1951-1989 (%), was the following:

1961-1965 (74.50 / 25.50),

1951-1955 (75.70 / 24.30),

1956-1960 (82.90 / 17.10),

1966-1970 (70.50 / 29.50),

1971-1975 (66.30 / 33.70),

1976-1980 (64.00 / 36.00),

1981-1985 (69.30 / 30.70),

1986-1989 (74.30 / 25.70).

Romanian industry was built on the basis of Western licences. The Communist Party aimed to develop the national economy and tried to avoid dependence on raw materials from other states.

A protest rally against the invasion of Czechoslovakia was held in Bucharest on August 21, 1968. Ceaușescu strongly condemned the armed intervention of the Warsaw Pact countries. As a result, he had a very good diplomatic relationship with NATO countries.

A series of official visits from western delegates to Romania were recorded, which included Charles de Gaulle in 1968, Richard Nixon in 1969, Henry Kissinger in 1974, and Valery Giscard d’Estaing in 1979. The Ceaușescu couple also visited western countries and met with their leaders. These visits included France and the USA in 1970, the USA again in 1973, and the United Kingdom in 1978.

Larger investments were made after 1968, primarily to industrial development (approx. 45% of the total investments), the construction of large factories and power plants, the implementation of new western technologies, the construction of dams, artificial lakes, railways, and roads (some with a strategic role, which would help the army defend against an invasion by the Soviet Union after 1968), viaducts, subway, military objectives, gigantic public buildings in Bucharest, etc.

As one can see in the 1990 Statistical Yearbook of Romania, all of these investments continued to grow rapidly from 1970 to 1986, after which the country saw a decline that reached its lowest point in 1989. Before 1970, investment in economic development were very slow.

The investments were grouped into two main categories: A and B. Category A concerned the means of production, steel, metallurgical, machine building, mining, and other heavy industries. This category benefited the most from investments (over 80% in the period from 1950-1989).

Category B consisted of both the industries producing goods for individual consumption that were necessary for family subsistence, as well as food, textiles, and leather industries. All these investments reached between 11% and 16% of total industrial investments.

The social changes resulting from these gaps were commensurate. The greater the gap between heavy and light industries, the worse the standard of living of the common population was. Moreover, massive investments in a given industry generated changes in the population structure.

On the one hand, the number of employees in all industries rose sharply, while the number of workers in agriculture, for example, who were needed to provide food, decreased. On the other hand, the overall levels of industrial production greatly increased.

The highest growth only lasted a decade, from 1970-1980. Between 1950 and 1989, production increased 44 times, with an annual average of 10.2%. The industrial branches included in the first category increased 61 times, and those in the second category only 25 times, with an annual average of 11.1% and 8.6%.

Industrial production per capita greatly increased, especially after 1970, in branches such as electricity (130 > 3276 kWh), the mining industry (coal extracted 239 > 2871 kg), cars (1 in 1960 > 62 per 10000 inhabitants), refrigerators (1 in 1960 > 20 per 1000 inhabitants), televisions (14 in 1970 > 22 pieces 1000 inhabitants), fabrics (12 > 48 m2), meat (9 > 30 kg), sugar (5 > 30 kg), cheese (1 > 4 kg), etc.

At the same time, one must point out the excessive increase in the production of finished products such as steel, which was necessary for the development of heavy industry. For example, in 1989 the per capita steel production was 621 kg, far exceeding production levels in other countries with a heavy industry tradition, such as France (319 kg), the USA (363 kg), and even Sweden (577 kg).

These investments strangled the national industry in an unintentional way (e.g., following the example of Japan, where the authorities invested in siderurgy). For example, in Romania there were seven steel plants and approximately six refineries, in a country that did not produce iron ore or coking coal.

The Communist Party did not necessarily want to reduce production costs. The party’s plan was to increase production especially for industrial branches, such as the construction of industrial machinery, thermal, and electrical energy, chemistry, metallurgy, and fuels. According to experts, from 1980 to 1989 the share of investments allocated to each of these branches in total industrial investments was between the following percentages: 17.7% - 28.9%, 10.8% - 25.2%, 13.2% - 22.1%, 9.5% - 14%, 7%, and 10% - 14.2%.

Therefore, the gradual growth of industrial production required huge sums of money in terms of the maintenance of work equipment. Therefore, the funds allocated to these industries increased from 21.7 billion lei in 1975 to 80.0 billion lei in 1987.

Massive investments in increasing production resulted in a large amount of goods that were of poor quality. This limited foreign trade in the export of industrial goods. The communist authorities could not export the low-quality goods to states with developed industries but only to certain underdeveloped states, where the price mattered but the quality did not.

Over the last decades of the regime, the disproportion of investments between the preferred branches of industry and the food industry deepened. For example, between 1980 and 1989, the food industry was allocated less than 5% of total industrial investment. The low supply of food on the domestic market led to an acute crisis among the population, especially amongst young people.

On one hand, the consumption of some basic foods gradually decreased after 1980, reaching its lowest point in the final years before the revolution. This led to the emergence of the “underground market”, which consisted of the sale of legal or illegal products at higher prices. This affected both the state budget and the standard of living in Romania.

A good number of the people who took advantage of this phenomenon were peasants, who raised animals and grew vegetables and fruits and could sell them illegally to the townspeople. In fact, the food crisis of the last decade of the communist regime was felt most acutely in large industrial cities that were dependent on the agricultural economy, and less so in smaller towns and villages.

There were also cases in which the citizens benefited from the support of rural relatives regarding basic foodstuffs. In many situations, the authorities allowed this indirectly, as they were aware of the difficult situation that members of society were going through. However, in rural areas the amount of vegetables, eggs, or meat produced by peasant households was far too small due to nationalization. Peasants were forced to give quotas to the state. Furthermore, domestic animals could not be slaughtered without approval, in an effort to stop peasants from selling meat illegally.

The main goal of Ceausescu's regime was industrial modernization. However, around 1980 heavy industry began to be economically unprofitable. The rapid growth of production capacity required the supply of raw materials and energy in quantities that could no longer be supported from national sources starting in 1980.

Authorities did not stop investing in heavy industry but resorted to importing raw materials and energy. This phenomenon led to production at a fast pace of poor quality and uncompetitive goods, due to outdated equipment and technology.

In order to alleviate the energy and raw material crisis, the authorities resorted to the same aberrant solutions, which had a negative social impact on certain communities and also affected the environment. In some regions, tens of thousands of people were displaced, and thousands of hectares of agricultural land were used to build coal mines.

Mihai Dragnea is associate researcher at the University of South-Eastern Norway. He is the president of the Balkan History Association and the editor of Hiperboreea, the journal affiliated to the association, published by the Pennsylvania State University Press. His interests and collaboration include cultural, social and political relations between Germans, Scandinavians and Wends during the High Middle Ages, Viking Age, early Slavic ethnicity and state formation, and identity and conflict in the Balkans during the last century.

Bibliography

Anuarul statistic al României (Bucureşti: Comisia Națională pentru Statistică, 1990).

Ban, Cornel, “Sovereign Debt, Austerity, and Regime Change: The Case of Nicolae Ceausescu’s Romania”, East European Politics and Societies, 6 (4) (2012): 743-776.

Banque mondiale, La pauvreté, Rapport sur le développement dans le monde 1990 (Washington DC, 1990).

Bardan, Alexandra, “Luxul, în comunism. Mutații semantice în economia de penurie din România anilor ’80”, Marian Petcu (ed.), Sociologia luxului (București: Tritonic, 2015), 207-245.

Burakowski, Adam, Dictatura lui Nicolae Ceauşescu 1965-1989. Geniul Carpaţilor (Iaşi: Polirom, 2011).

Deletant, Dennis, Ceaușescu and the Securitate: Coercion and Dissent in Romania, 1965-1989 (London: Hurst Publishers, 1995).

Dobrescu, Emilian, Ritmul creşterii economice – teorie şi analiză (Bucureşti: Editura Politică, 1968).

Grigorescu, Constantin (ed.), Dezvoltarea agriculturii în corelaţie cu industria (Bucureşti: Editura Politică, 1984).

Hall, Richard Andrew, “Theories of Collective Action and Revolution: Evidence from the Romanian Transition of December 1989”, Europe-Asia Studies, 52 (6) (2000): 1069-1093.

Moghioroși, Vlad, “Raportul Tismăneanu: Reacții și Dezbateri”, Hiperboreea, 1(2) 2014: 301-322.

Ordin nr. 4 din 5 aug. 2003, Monitorul Oficial, Partea I 576 12 aug. 2003 privind cursul oficial leu/dolar S.U.A. în perioada 1945-1989.

Petrescu, Cristina, “The Letter of the Six:’ On the Political (Sub)Culture of the Romanian Communist Elite”, Studia Politica, 5 (2), 2005: 355-384.

Tismăneanu, Vladimir, Raport final, Comisia Prezidențială pentru Analiza Dictaturii Comuniste din România (Bucureşti: Humanitas, 2007)