The Destruction of the Estonian Political Elite during the Soviet Occupation in 1940-1941

The policy of the Soviet Union in the territories it occupied were aimed at the destruction of the so-called “bourgeois state” as such. Private property and the legal order, democratic institutions, civil associations and so forth were liquidated, and their leaders were killed. The article of Estonian historian Indrek Paavle brings to light how a significant portion of Estonia’s political and social elite was imprisoned, deported or killed during the Soviet occupation in 1940–1941.

This article is previously published in a memorial collection “At the Will of Power. Selected articles”. it contains the most important and best part of his research. The book can be purchased online from the National Archives of Estonia, Apollo and Rahva Raamat.

This overview does not account for all people who could have been included under the concept of the elite. Thus for the time being, the Estonian business elite – industrialists, bankers, people active in commerce and others, of which many were imprisoned by the officials of People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs and People’s Commissariat for State Security of the Soviet Union (hereinafter USSR) and sent to prison camps in Russia or killed – has been left out of this systematic survey. The fate of Estonian military officers has already been considered in detail earlier.

The object of the following treatment is the fate of Estonia’s heads of state, ministers, members of the Riigikogu (Parliament of the Republic of Estonia), judges, members of local municipal councils and higher government officials. Generally speaking, this survey is limited to those who were in office immediately prior to the occupation of Estonia by the USSR. As an exception, only the fates of all heads of state and ministers who had been in office between 1918–1940 are considered.

The consideration of judges here is limited to the staff of the last composition of each of the two highest courts and the Kohtukoda (Court Chamber). The overview also includes the composition of the last Riigikogu and the last local municipal councils, and government officials who were in office in 1940. The listing of members of municipal councils is limited to the mayors of the larger cities and towns. The pay scale was adopted as the basis for the analysis of government officials, which is limited to officials at the top six salary levels who were appointed to office by the President of the Republic in accordance with the Regulation of Government Act of 1938. The appointment and dismissal of these officials was published in the “Riigi Teataja” (State Gazette) and to a certain extent, this made it easier to ascertain their nomenclature. The fate of prosecutors is also not analysed in the following overview.

The data is not quite exhaustive. The number of people imprisoned and/or deported and/or killed may be a little larger because all the data concerning all the victims of the NKVD and NKGB in Estonia has not yet been compiled. In some cases, however, the data contained in lists of imprisoned people is too scanty for the identification of individuals. In particular, this concerns individuals with more frequently recurring family names whose dates of birth and father’s names are not known.

Heads of state of Estonia

According to the first Constitution of the Republic of Estonia that went into effect on 21 December 1920, Estonia was a parliamentary republic without the institution of the head of state. However, since the Constitution gave the prime minister some ceremonial functions that usually belong to the president along with the official title Riigivanem (Elder of State) that accentuated them, the Riigivanems can be considered heads of state.

The amendment to the Constitution that went into effect on 24 January 1934 broadened the limits of power of the Riigivanem, who from that point onward was the head of state elected directly by the people for a term of five years. Elections of the Riigivanem and the Riigikogu were to be held in April of 1934. The right wing radical Eesti Vabadussõjalaste Liit (War of Independence Veterans League) did well in the municipal elections that took place at the turn of the year (end of 1933) and a continuation of that success was anticipated in the elections of the Riigivanem and the Riigikogu as well.

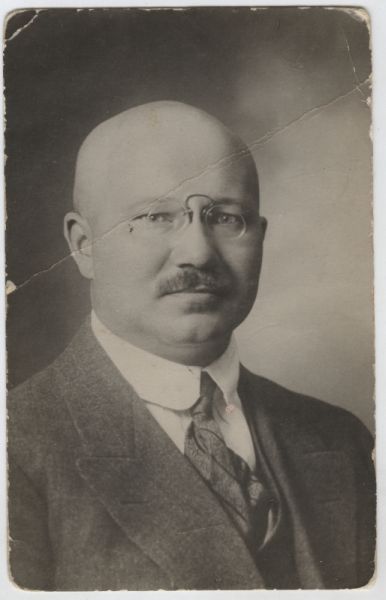

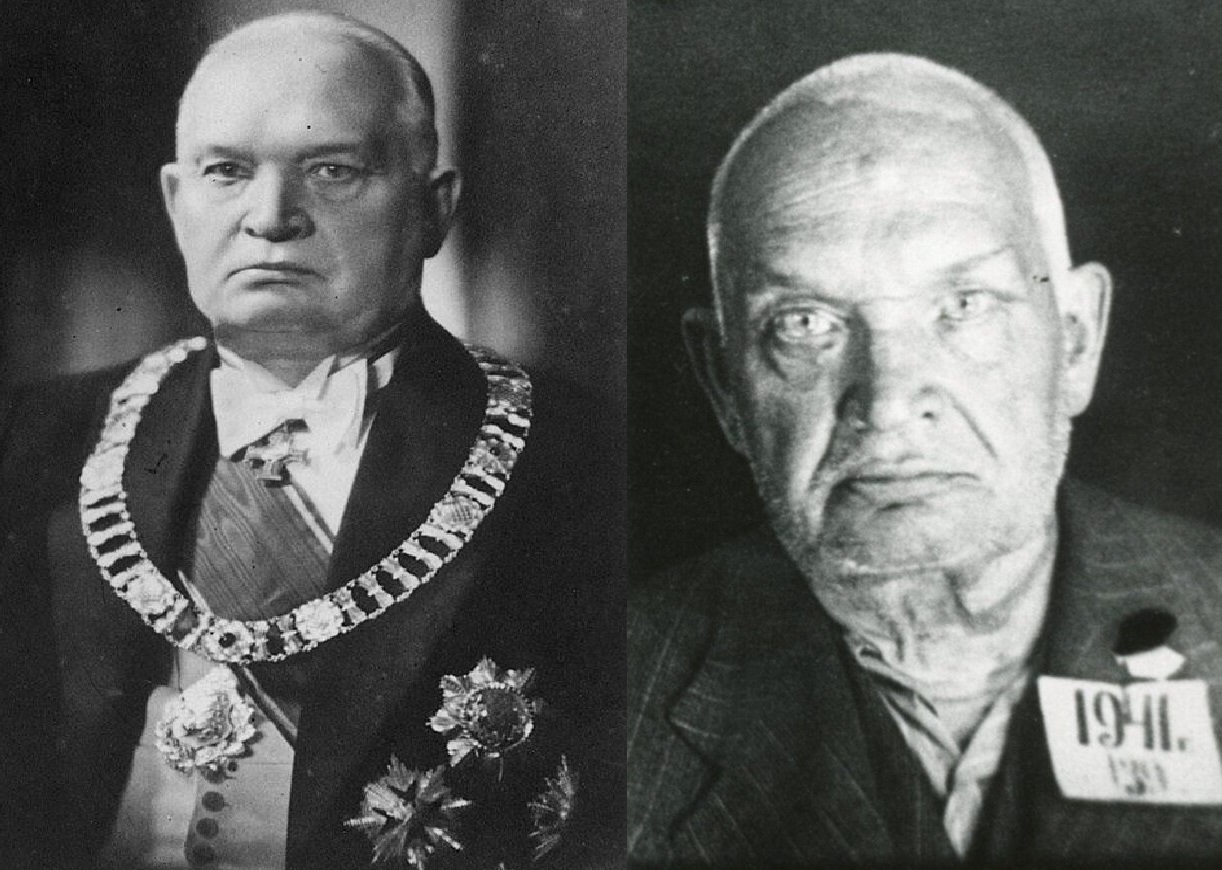

Riigivanem Konstantin Päts and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces General Johan Laidoner carried out a military coup on 12 March 1934 to forestall the War of Independence Veterans League from coming to power. A state of emergency was declared for a period of six months and subsequently repeatedly extended. The elections were postponed until after the repeal of the state of emergency. Konstantin Päts was the head of state from the time of the coup until the end of Estonian independence, initially as the Riigivanem, from September of 1937 to April of 1938 as the Riigihoidja (Protector of State), and as President of the Republic as of 24 April 1938 after the new Constitution came into effect and presidential elections were held.

Eleven men held the office of head of state in Estonia in 1918–1940. (3 provisional governments were in office from 24 February 1918 until 9 May 1919. Since they all were led by Konstantin Päts, this does not increase the total number of heads of state.) Of these men, only August Rei was spared. He was the Envoy of the Republic of Estonia in Moscow in 1940 and he succeeded in escaping to Sweden via Riga in July of 1940. Otto Strandman shot himself on 16 February 1941 after he received a summons to appear at the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs. The remaining 9 men were imprisoned by the NKVD and NKGB in 1940–1941.

President Päts was on 30 July 1940 deported to Ufa together with his son Viktor Päts, Viktor’s wife Helgi and their children Matti and Henn. They lived in Ufa until the beginning of war between the Soviet Union and Germany as deportees banished into exile. After the beginning of the war, Päts was imprisoned along with Viktor and Helgi Päts. All three were convicted and sent to prison camp; the children were placed in an orphanage.

Viktor Päts died in prison camp, Henn Päts died in the orphanage. Helgi Päts and Matti Päts managed to make their way back to Estonia after the end of the war. Konstantin Päts was brought to Estonia and committed to the Jämejala mental hospital near Viljandi in 1954 after Stalin’s death but was soon taken back to Russia where he died on 18 January 1956 in the Burashevo mental hospital near Kalinin (Tver).

Former Riigivanems Friedrich Akel and Jüri Jaakson were sentenced to death and executed by firing squad, the former on 3 July 1941 in Tallinn and the latter on 20 April 1942 in Sosva prison camp in Sverdlovsk oblast. Ado Birk was also sentenced to death. He died on 2 February 1942 in Sosva prison camp before his sentence could be carried out. There is no absolutely confirmed information concerning the fate of Jaan Tõnisson and Jaan Teemant but it is most likely that both were executed by firing squad in Tallinn in July 1941 after the beginning of the war between the USSR and Germany.

Ants Piip was imprisoned on 30 June 1941 and died on 1 October 1941 in Perm prison camp. Both Kaarel Eenpalu and Juhan Kukk were sentenced to prison camp and both men died shortly thereafter: the former on 27 January 1942 in Vyatlag prison camp and the latter on 4 December 1942 in the Archangel oblast.

Members of the government cabinets

The 1920 Constitution concentrated power in the hands of the Riigikogu. Since a rather large number of political parties operated in Estonia and coalitions changed rapidly, changes in the composition of the government were frequent. For this reason, over the course of 22 years, 105 men were members of the governmental cabinet in addition to the 11 Riigivanems previously mentioned. This total includes 16 ministers who belonged to the three Provisional Governments in office during the years 1918–1920 prior to the adoption of the Constitution who did not become ministers later.

19 former ministers had died by the time the Soviet occupation began and 2 (Jüri Annusson and Johannes Kartau) had left Estonia. Rudolf Gabrel apparently died a natural death on 20 July 1940. Six former ministers were in the foreign service in the summer of 1940 and did not return after the occupation of Estonia. Seven former ministers left Estonia to Germany as part of the resettlement (Umsiedlung in German) and late resettlement (Nachumsiedlung) of Baltic German minority in 1939–1940 and 1941.

Thus 73 former ministers remained in occupied Estonia. Theodor Rõuk committed suicide on 21 July 1940. The NKVD and NKGB imprisoned 49 men in 1940–1941. Ernst Constantin Veberman committed suicide in prison and Hans Rebane escaped from a ship transporting prisoners from Tallinn to Leningrad in August of 1941 that was hit by a torpedo in the Gulf of Finland and was steered aground on the Estonian coast. He left Estonia in 1944.

Of the remaining ministers, two survived imprisonment: Paul Kogerman and Peeter Kurvits. Forty-five men perished in prison camp and of these at least 15 were sentenced to death and executed by firing squad. (It is not always certain whether a person died in prison camp after his death sentence was passed and before the sentence could be carried out or if he was actually executed. Although the difference is not great, this must nevertheless be taken into account in the interest of attaining the greatest possible precision).

Former minister and long-time State Auditor General Karl-Johannes Soonpää was killed in action in the ranks of the Omakaitse (Home Guard) fighting against Red Army paratroopers in the summer of 1944. Soviet state security institutions arrested 10 former ministers after the war and five of them survived their imprisonment. Since several former ministers succeeded in leaving Estonia in 1944 (Jaan Raudsepp perished in Dresden in March of 1945 during an Allied air raid), it can therefore be inferred that of the ministers remaining in Estonia after the beginning of the occupations, only Adam Bachmann (Randalu), Konstantin Treffner and Jaan Masing were not imprisoned.

The Ministry of State Security (MGB) officials tried to use Adam Randalu after World War II in espionage operations directed against Estonian exiles in Sweden. Konstantin Treffner was the headmaster of the Hugo Treffner Boys Grammar School in Tartu, the largest in Estonia, in 1917–1940. He was dismissed from his position in the summer of 1940 along with most other headmasters yet according to existing data remained untouched by repressions perpetrated against individuals.

Of the 11 ministers of the last government of the Republic of Estonia, only Prime Minister Jüri Uluots managed to avoid imprisonment. The remaining 10 were arrested during the first year of occupation. Of them, Minister of Education Paul Kogerman was released from prison camp in 1945. The remainder, however, perished: Minister of War Nikolai Reek, Minister of Social Affairs Oskar Kask, Minister of Communications Nikolai Viitak and Minister without portfolio in the duties of Head of the State Propaganda Administration Ants Oidermaa were executed by firing squad; Minister of Internal Affairs August Jürima, Minister of Justice Albert Assor, Minister of Agriculture Artur Tupits, Minister of Foreign Affairs Ants Piip and Minister of Economic Affairs Leo Sepp died in prison camps in Soviet Union.

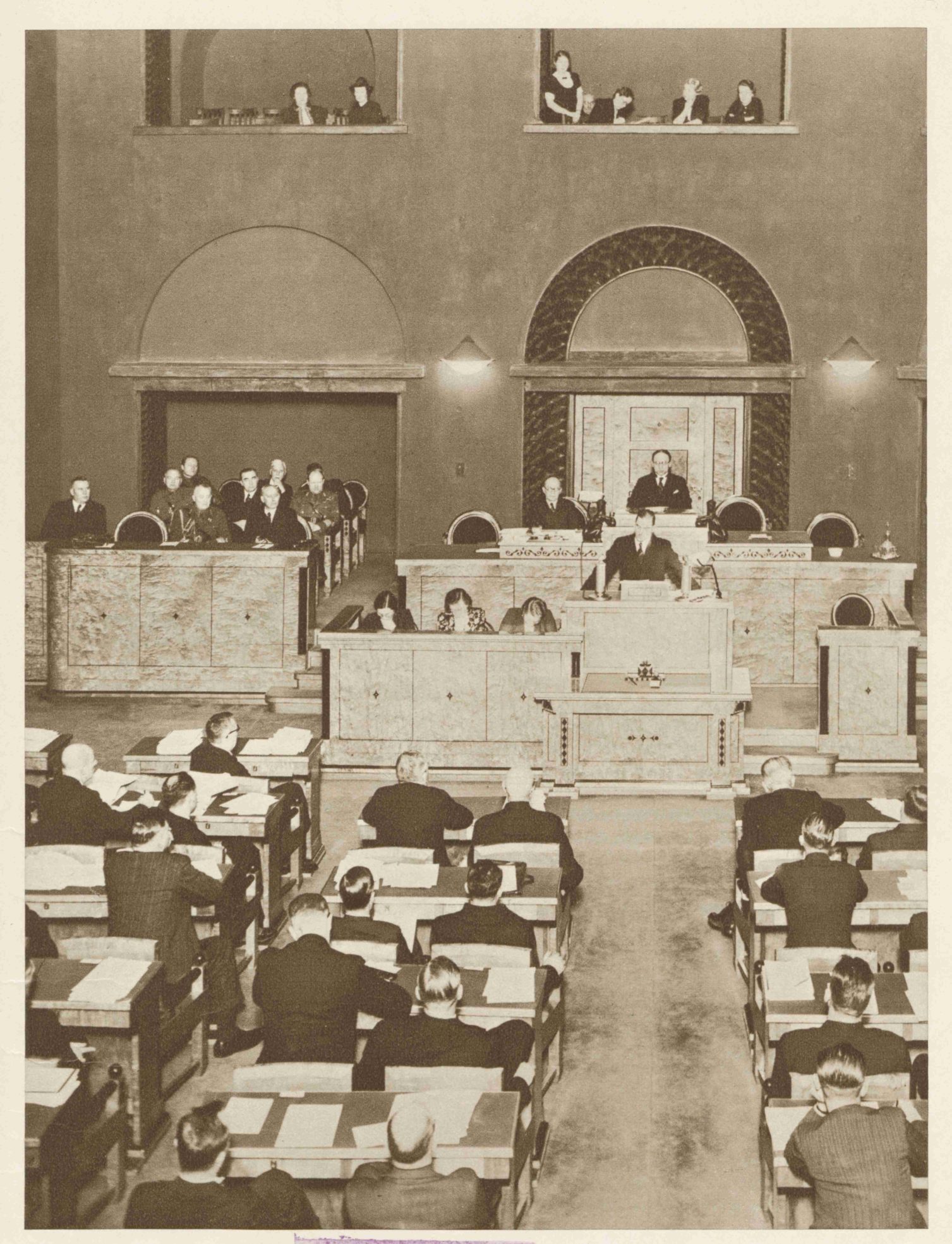

Members of the 6th Riigikogu (1938–1940)

According to the 1938 Constitution, the Riigikogu was a two-chamber representative assembly consisting of the Riigivolikogu (Representative Assembly, lower house), consisting of 80 elected members, and the 40 member Riiginõukogu (Council of State, upper house).

Six members of the Riiginõukogu were ex officio members: the Commanderin-Chief of the Armed Forces, the Bishops of the Estonian Evangelical Lutheran Church and the Estonian Orthodox Church, the rectors of the University of Tartu and Tallinn Technical University and the president of the Bank of Estonia. Twentyfour members of the Riiginõukogu were elected by local municipal councils and the professional chambers as well as representatives of the Kaitseliit (Defence League), ethnic minorities and others. The President of the Republic personally appointed 10 members of the Riiginõukogu.

Nineteen members of the Riiginõukogu were imprisoned in 1940–1941. None of them survived: 8 were executed by firing squad, 7 died in prison camps prior to sentencing and 4 during their term of imprisonment. One member of the Riiginõukogu was imprisoned in 1944 and he also died in prison camp. At least 12 former members of the Riiginõukogu escaped to exile in the West. According to data available thus far, 8 members of the Riiginõukogu remained untouched by repressions perpetrated against individuals.

Member of the Riiginõukogu and Commander-in Chief of the Armed Forces Johan Laidoner was deported from Estonia on 19 July 1940 already. He died on 13 March 1953. President of the Bank of Estonia Jüri Jaakson was executed by firing squad in Sosva on 20 April 1942.

Well-known industrialist and chairman of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry Joakim Puhk was executed by firing squad in Kirov oblast on 14 September 1942. Chairman of the Riiginõukogu Mihkel Pung died in Sosva prison camp on 11 October 1941.

Forty of the 80 members of the Riigivolikogu were imprisoned in 1940–1941. Only one of them managed to survive imprisonment. He was released from prison camp in 1948. Twenty-six members of the Riigivolikogu were sentenced to death in 1941–1942 and executed by firing squad, five died during the preliminary investigation and eight died in prison camps in Soviet Union after being sentenced to 8–10 years in prison.

The first arrests of members of the Riigivolikogu were made in July of 1940 already. Ado Anderkopp was arrested on 22 July 1940 and executed by firing squad on 30 June 1941 in Tallinn. His arrest could have been caused by the spontaneous anti-soviet public demonstration that followed the football match between Estonia and Latvia at Kadriorg Stadium in Tallinn on 18 July 1940.

Many leaders of Estonian sports organisations were subsequently arrested, among them the chairman of the Estonian Football Association Anderkopp. Ado Roosiorg was arrested on 28 July (he died in Karaganda oblast on August 15, 1942); Viktor Päts was deported with his father to Ufa on 30 July 1940 (see above), arrested on 26 June 1941 and died in Butyrka Prison in Moscow on 4 March 1952.

Members of the Riigivolikogu Märt Rõigas and Karl Roomet were killed in action as forest brothers in the summer of 1941. Neeme Ruus and Henn Treial were executed during the German occupation. Six members of the Riigivolikogu were imprisoned by Soviet state security institutions after the end of the war. Four of them were released after the death of Stalin. Oskar Gustavson was killed in 1945 while attempting to escape from interrogation.

At least 15 members of the last Riigivolikogu escaped to exile in the West. One of them (Rudolf Penno) was actually arrested by the NKVD on 22 July 1940 but was released from preliminary investigation in the same year. The fate of the remaining 14 members of the Riigivolikogu is not known but they are not included in the existing lists of individuals imprisoned by the occupying powers.

Judges

The Riigikohus (Supreme Court) was the highest court of the Republic of Estonia. The circuit courts of Tallinn, Tartu, Rakvere and Pärnu were the next highest courts. The task of the Kohtukoda (Court Chamber) was primarily to review the decisions of the circuit courts.

The Riigikohus had 16 members in 1940. The long-time Chairman of the Riigikohus Kaarel Parts died of natural causes on 5 December 1940. Six Justices of the Riigikohus were imprisoned in 1940–1941. They all perished in prison camps and two died after the war. In addition, one Justice of the Riigikohus perished in the Baltic Sea while escaping from Estonia in the autumn of 1944. In addition to Parts, one other Justice of the Riigikohus died in 1940. Five Justices of the Riigikohus were not imprisoned.

The staff of the Kohtukoda and the four district courts was 70 judges in 1940. Fifteen judges were arrested in 1940–1941 and all of them perished in prison camps. Six of them were executed by firing squad or died before their death sentence could be carried out. One judge perished in the Baltic Sea while escaping from Estonia in the autumn of 1944 and 7 former judges were imprisoned after the war.

Government officials

Data concerning 133 higher government officials has been assembled. The most important of them are the Legal Chancellor and the State Auditor, since they were appointed to office according to special decree. Legal Chancellor Anton Palvadre was arrested in 1941 and died on 16 January 1942 before his death sentence could be carried out. State Auditor Karl-Johannes Soonpää perished in the summer of 1941.

The 1st salary level included 17 government officials: the head of the State Chancellery, the heads of the chancelleries of both the Riigivolikogu and the Riiginõukogu, the director of the President’s Office, the chairman of the Commerce Committee and assistant ministers. Assistant Minister of Internal Affairs and former inspector of the Political Police August Tuulse committed suicide together with his wife Nelli on 23 June 1940. Eight officials left Estonia in 1944 and the remaining 8 were imprisoned in 1940–1941.

Assistant Ministers of Economic Affairs Colonel Voldemar Karing and Eduard Vendelin were executed by firing squad. Long-time Assistant Minister of Social Affairs Alfred Mõttus, Assistant Minister of Communications Karl Jürgenson, and Karl Tofer, who briefly served as Assistant Minister of Foreign Affairs, died before the decision was passed. Head of the State Chancellery Karl Terras, Assistant Minister of Agriculture Jaan Luik and Chairman of the Commerce Committee of the Ministry of Economic Affairs August Teose died soon after sentencing in different prison camps in Soviet Union.

The 2nd through 6th salary levels included the directors of various structural units of government agencies: the directors and deputy directors of departments and offices, bureau managers, advisors and others. Police Prefects, some of whom earned less than the 6th salary level, are also included in this group.

Of the 114 officials of this category in office in 1940, at least 30 men were imprisoned in the years 1940–1941. Of them, Director of the Department of Trade of the Ministry of Economic Affairs Eugen Uuemaa committed suicide in prison on 25 July 1940,23 11 were executed by firing squad, 16 died in imprisonment and only two managed to survive until their release.

In addition to them, Director of the Department of Youth and Liberal Education of the Ministry of Public Education Colonel Johannes Vellerind died on 6 July 1941 of injuries inflicted during interrogation. Another 4 higher governmental officials were imprisoned in 1944–1951 and one perished in the Baltic Sea in the autumn of 1944 while escaping from Estonia.

Examination of the timeline of arrests indicates that higher police and economics officials were the first to be arrested. Two important senior leaders of the police were arrested on 23 June already: the Tallinn Commissar of the Political Police Julius Edesalu and the Deputy Director (in the field of the political police) of the Police Administration Konstantin Kirsimägi.

Ants Kukk was dismissed from his position as Director of the Tax Administration of the Ministry of Economic Affairs on 19 July 1940 and was arrested on the same day. He was sentenced to 8 years in labour camp and died in Karaganda oblast on 26 August 1942.

The arrest of the remaining senior leaders of the police followed. Over the course of 1940, Director of the Police Administration Juhan Sooman (18 September 1940), Prefect of Railways Hans Kuben (16 September 1940), Prefect of Viljandi-Pärnu Jakob Vares (19 September 1940) and Prefect of Tallinn-Harju Nigul Reimo (24 September) were all imprisoned in addition to Kirsimägi. Kirsimägi and Sooman were executed in Soviet Union and the others died over the course of less than a year in prison camps. Of the 9 Prefects eight were imprisoned in 1940–1941.

By the autumn of 1942, they had all died or been killed. Prefect of Saare-Lääne Leonid Kane was arrested on 28 January 1941. He was sentenced to death on 12 May 1941 and the sentence was carried out in Tallinn on 23 June 1940. The War Counsel of the Supreme Court of the USSR had reduced his sentence to 10 years in prison on 20 June 1941 but despite of that he has been executed by firing squad. Prefect of Tartu-Valga Viktor Roovere managed to hide from the NKVD and was the only one to escape repressions. He served at his former post in 1941–1944 and left Estonia in 1944.

The remainder of arrests took place in 1941, beginning with the arrest of long-time Head of the State Chancellery Karl Terras on 7 January 1941.

Officials of local governments

The system of local municipal government was two tiered in the Republic of Estonia. Alongside towns and rural municipalities, Estonia was divided into 11 counties that were administered by county elders. There were 33 towns in Estonia in 1940. These were divided into the capital and first (over 50,000 inhabitants), second (10,000–50,000 inhabitants) and third tier (under 10,000 inhabitants) towns. Tartu was a first tier town, and Narva, Pärnu, Nõmme, Rakvere, Valga and Viljandi were second tier towns. The fates of county elders and the mayors of first and second tier towns are examined below.

Estonia was divided into 248 rural municipalities after the local government reform of 1939. The rural municipalities of Pakri and Naissaar on islands of the northern coast of Estonia were eliminated in the summer of 1940 because the entire territory of these rural municipalities was placed at the disposal of the Red Army and the population was evacuated to the mainland.

The last rural municipality council elections took place in October of 1939 and the last rural municipality administrations assumed office at the beginning of 1940. According to the Rural Municipality Act, rural municipality administrations consisted of the rural municipality elder and one to three deputies. The number of deputies was determined depending of the size of the rural municipality.

By the beginning of 1940, a total of 248 rural municipality elders and 529 deputy elders assumed office. Of these, 4 rural municipality elders and 10 deputies were replaced from that position until August of 1940. Some of these changes took place after the beginning of the Soviet occupation, but since all of these changes were initiated earlier and not a single member of any rural municipality administration was dismissed from office for political purposes prior to 1 August 1940, I consider the personnel that was in office on 31 July 1940 to be the composition of the last rural municipality administrations of the period of independence.

All former rural municipality administrations were removed from office on 1 August and new administrations were appointed. A proportion of 10.6% of rural municipality elders and 10.8% of deputy elders remained in office. The last rural municipality elders and deputy elders of the period of independence were displaced from the administration of rural municipality life in February of 1941 when local executive committees were formed according to the Soviet model.

The Rural Municipality Act that was put together in the era and spirit of an authoritarian rule gave the rural municipality elder broad jurisdiction and furthermore, they were as a rule influential men who had administered their rural municipalities for years, so-called local opinion makers. Alongside rural municipality elders, rural municipality clerks were influential men in the rural municipality and were also traditionally among the most educated men in their villages. Many of them had been in office for the entire period of independence.

Since the influence of Soviet authority was particularly weak in rural areas in 1940–1941, the rural municipality elders and clerks posed a direct threat to their occupying power. Many of these men also occupied key positions in local chapters of the Kaitseliit (Defence League) and/or Isamaaliit (Fatherland League, the only legal political party from 1935) and this gave the NKVD/NKGB formal grounds for their imprisonment.

County elders

Only two of the last county elders managed to escape: Viljandi County Elder Mihkel Hansen and Harju County Elder Paul Männik left Estonia in 1944. Mihkel Hansen died in Toronto at the end of 2004. Five men, Lääne County Elder Artur Kasterpalu, Tartu County Elder Heinrich Lauri, Pärnu County Elder Jüri Marksoo, Saare County Elder Hendrik Otstavel and Võru County Elder August Kohver were arrested in 1941. Kasterpalu and Otstavel were executed in 1942. Lauri was also sentenced to death but he had already died in prison camp by then. Marksoo died of myocarditis in a prison camp infirmary during his preliminary investigation and Kohver died in prison camp in 1942.

Järva County Elder Juhan Kaarlimäe, Viru County Elder Karl-Eduard Pajos, Valga County Elder Värdi Velner and Petseri County Elder Mihkel Tang were arrested in 1944–1945. The former three were county elders during the German occupation as well and Tang was a deputy elder in Viru County.

Pajos died in prison camp in 1953. Kaarlimäe was released in 1954 and Velner was released a year later. Both returned to Estonia. Kaarlimäe was arrested again in 1969 and was in prison for a short time. Tang went into hiding in 1941. He was arrested on 28 October 1944 and died on 8 July 1946 in a prison camp in Leningrad oblast, where he had been sent for 10 years.

Mayors

Of the mayors of the larger towns, the last Mayor of Tallinn, retired Major General Aleksander Tõnisson was arrested first of all and executed by firing squad in Tallinn on 30 June 1941. In addition, Mayor of Tallinn Anton Uesson and Mayor of Rakvere Heinrich Aviksoo were also executed by firing squad.

Long-time Mayor of Viljandi August Maramaa was arrested in 1941 and died the following year in prison camp in Kirov oblast. (The primary reason for his arrest was the fact that his son Ülo was one of the leaders of the Salvation Committee underground resistance organisation founded in July of 1940.) Mayor of Nõmme Ludvig Ojaveski committed suicide in his home on 6 August 1940.

The mayors of Tartu, Narva, Pärnu and Valga were not imprisoned according to presently available data. Mayor of Tartu Robert Sinka was mayor in 1941 as well after the departure of the Red Army. He escaped into exile in 1944 and later worked as a doctor at St. Anthony’s Hospital in New York.

Members of rural municipality administrations

Thirty-eight rural municipality elders are known to have been imprisoned in 1940–1941: 7 from Lääne County, 6 from Viru County, 4 from Järva County, 3 from each of Harju, Petseri, Saare, Tartu and Võru counties, and 2 from each of Pärnu, Valga and Viljandi counties.

Of these, 34 perished in 1941–1942: 15 were executed by firing squad, 7 died after sentencing in prison camp and 12 died in the course of preliminary investigation. Four men managed to survive imprisonment and return to Estonia years later. In addition to these 38, two rural municipality fell victim to the terror in the summer of 1941: elder of Kasepää rural municipality August Oja was killed by members of the NKVD destruction battalions and Kuressaare rural municipality elder Aleksander Raudsepp was murdered in Kuressaare Castle Park.

Two rural municipality elders were executed during the German occupation. Paide rural municipality elder Jaan Krass was executed in Paide by decision of the German Security Police on 7 May 1942. He was accused of being a candidate member of the Estonian Communist (Bolshevist) Party, the chairman of the Executive Committee of the Järva County Soviet of Representatives of Workers and Peasants and a deputy chairman of the Commission for the Organisation of Land Use and Reform, and also of participating in deportation and making communist speeches.

On the same day, Vaoküla rural municipality elder Johan Heldemaa was executed in Valga for communist activities. Another 73 rural municipality elders were imprisoned by Soviet state security institutions in 1944–1955. Thus, a total of 111 rural municipality elders were imprisoned during the Soviet occupation.

Valga County Tõlliste rural municipality elder Artur Gross was the very first to be arrested on 30 August 1940. He was initially held in Tallinn Central Prison and was sentenced on 8 March 1941 to 8 years of forced labour according to § 58-4 and 58-10 of the Penal Code of the Russian SFSR. He was sent to Siberia where he died of sclerosis of the heart aorta on 30 June 1942 at the age of 60.36 Why Gross was imprisoned so early is not clear from the materials of his investigation.

He was a rather “average” Estonian rural municipality elder: a farmer with an elementary school education who owned his farm. Gross was 58 years old at the time of his arrest and had previously been rural municipality elder for 14 years beginning in 1908 (1908–1917, 1918, 1930–1934). Most of the rural municipality elders who were in office in 1940 had extensive experience in office but very few had experience extending back to the pre-independence era.

Twenty-eight deputy elders were imprisoned in 1940–1941. An additional 93 deputy elders were imprisoned in 1944–1955, bringing the total to 121 men. Four deputy rural municipality elders were executed during the German occupation. The office of deputy rural municipality elder emerged very rarely in the investigation process.

The reasons for imprisonment were still the “traditional” factors: participation in “organisations hostile to the people”, being declared a kulak, membership in the Omakaitse and other such charges. In addition, many pre-war deputy rural municipality elders served as rural municipality elders during the German occupation, usually when the rural municipality elder himself had been imprisoned in 1940–1941.

The fate of rural municipality clerks is comparable to that of rural municipality elders. Forty-five of the clerks of 1940 were imprisoned in 1940–1941. Three of them had also been in office as clerks of the local executive committees. Significant variations stand out between counties – while not a single clerk was arrested in Järva, Pärnu and Valga counties, more than a third of the clerks from Viru County (13 men) were arrested, as were nearly two thirds of the clerks from Saare County (10 men).

The fact that these counties were the latest to be captured in 1941 by the German forces can be considered one of the reasons for this. Another reason could be the fact that since they were indispensable people from the standpoint of the functioning of local institutions, they could not be arrested before the last possible moment, so to speak.

The fate of the imprisoned rural municipality clerks was disconsolate. Twenty-one men were executed in Soviet prison camps (primarily in the Sevurallag camp in Sverdlovsk oblast), 13 died in the course of preliminary investigation in 1941–1942 (two of them were sentenced to death posthumously) and one died in prison camp in 1942.

Two clerks from Saaremaa fell victim to the killings perpetrated in Kuressaare Castle Park from July to September of 1941. One clerk was released from prison camp in 1957 and another two arrested clerks were liberated from Harku camp in August of 1941 when the German forces arrived.

Three clerks from the era of independence were executed during the German occupation. All of them were accused of being “active communists”. Another 32 clerks from the era of independence were imprisoned in 1944–1952, nevertheless considerably less than the number of rural municipality elders arrested.

The reason was that although both the remaining rural municipality elders and clerks mostly worked at the same posts during the German occupation as well, rural municipality elders were accused of “collaboration with the occupation authorities” while clerks were not for the most part. The leader principle was in effect during the German occupation in local municipal administrations as well. Elders had greater relative fullness of power compared to previously and the extent of responsibility of other officials, including the clerk, decreased respectively. Most of the 32 men imprisoned after the war managed to survive the years in prison camp and return to Estonia in the second half of the 1950’s.

Summary

Generally speaking, people were not convicted for working in any particular official position or membership in any particular representative assembly although these circumstances emerged on the agenda in the course of investigation. The grounds for conviction or arrest was usually the membership of the victims in so-called “organisations hostile to the people” like the Kaitseliit or Isamaaliit.

As a matter of course, educated people who were socially active and were among the leaders of these organisations had also risen to leading positions in political life. Thus one is closely associated with the other in this case. It is also characteristic that whenever possible, orders of merit of the Republic of Estonia (the Cross of Liberty, the Arms of Estonia Order of Merit, the White Star, the Cross of the Eagle, and others) earned by the accused are always mentioned in the accusations.

Counterrevolutionary and anti-labour movement activity was also a widespread accusation, the proof of which was mostly considered to be working at some leading official position. In some cases, participation in some specific event was added to the accusation, such as participation in the suppression of the attempted communist revolt of 1 December 1924 or the revolt of 1919 in Saaremaa. Sometimes, especially in the case of judges, the accusation also included participation in trials of so-called labour movement activists in 1918–1940.

A significant portion of Estonia’s political and social elite was imprisoned, deported or killed during the Soviet occupation in 1940–1941. In the space of one year, Soviet security institutions arrested 4/5 of the former heads of state of Estonia, 2/3 of its former ministers, including 10 of the last 11 ministers, half of the members of the last Riigivolikogu and almost half of the members of the last Riiginõukogu, 3/8 of the staff of the last Supreme Court, over a quarter of its higher government officials (including nearly half of its highest level officials), nearly half of the last county elders and 1/6 of its rural municipality elders and clerks. The overwhelming majority of those arrested in 1940–1941 perished within the subsequent couple of years and only a few managed to return to their homeland in the post-war years.

Arrests continued after the war and if they no longer affected the target groups considered here to the same extent, then only because the people in question had already been imprisoned, perished or fled from Estonia. Many were spared from imprisonment because they were beyond the reach of the Soviet state security institutions at the time.

The reason for sparing some government officials was also the necessity of maintaining a certain continuity of knowledge and competence. Yet the energetic action of Soviet state security institutions in recruiting agents also cannot be ignored. This does not at all mean that all officials who were spared from imprisonment had been recruited as agents a priori but in many cases this possibility cannot be ruled out.

The suicides that anticipated arrest must also be considered victims of Soviet terror. Six suicide cases are known among the men considered above: Riigivanem Strandman, ministers Rõuk and Vebermann, government officials Uuemaa and Tuulse, and Mayor Ludvig Ojaveski decided to end their lives. The imprisonments, deportations and killings of 1940–1941 gave rise to the willingness of Estonians to cooperate with the German occupying authorities. The massive flight of Estonians from their homeland in the autumn of 1944 was also a result of the repressions of 1940–1941.

The physical destruction of people – execution by firing squad or imprisonment for years in prison camp – was only a part of the repressions. Many who were not physically destroyed were nevertheless forced to abandon their occupation and established way of life. Many highly qualified and experienced people from various fields and spheres of activity had to work as unskilled labourers to support themselves, to lead a miserable life and suffer want, and to live in constant fear of terror.

Many were forced to collaborate with Soviet state security institutions, resulting in suffering for those who fell into the hands of Soviet state security institutions through the fault of the agents and at least moral suffering for the agents themselves.

It follows from the aforementioned data that the sovietisation policy brought on the destruction of the institutions of the Republic of Estonia and the bearers of those institutions: politicians, ministers, members of local municipal administrations and government officials. The occupying authorities of the Soviet Union did not recognise the Peace Treaty of Tartu between the Republic of Estonia and Soviet Russia signed in February of 1920 by which Soviet Russia recognized the independence of the Republic of Estonia, and treated the Republic of Estonia as a national formation that arose as the result of “counterrevolution”.

The 1926 penal code of the Russian SFSR was applied in court procedures, and sentences were meted out on this basis for deeds that mostly comprised of carrying out the functions of public office in the Republic of Estonia. The policy of the Soviet Union in the territories it occupied were aimed at the destruction of the so-called “bourgeois state” as such. Private property and the legal order, democratic institutions, civil associations and so forth were liquidated, and their leaders were killed or sent to prison camps.

The repressions of the occupying powers of Nazi Germany were directed against political opponents and communists and also derived from the objectives of their racial policy. For this reason, very few functionaries of Estonia’s state government and local municipal administrations fell victim to German security organisations.

This article is previously published in a memorial collection “At the Will of Power. Selected articles”. it contains the most important and best part of his research. The book can be purchased online from the National Archives of Estonia, Apollo and Rahva Raamat.

Indrek Paavle (born in 1970) has graduated from the Department of History in the University of Tartu in 1998 (cum laude) and defended a master thesis on topic “The institution of the Rural municipality in Estonia 1940-1941” and he defended his doctoral dissertation in 2009 (Sovietisation of Local Administration in Estonia 1940–1950). Indrek Paavle was awarded the Science prize of Lennart Meri in 2010 for his dissertation. In 2012 he was awarded the 15 000 euro grant for compiling Otto Tief's academic biography. He has worked in the National Archives, the Estonian Foundation for the Investigation of Crimes against Humanity and the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory. He was one of Estonia’s most prominent historians, who tragically perished in 2015.

Sources and literature:

Collection of files of unconcluded investigations, Department of Estonian State Archives (Eesti Riigiarhiivi osakond, hereinafter ERAF) holding SM 129; Collection of files of closed investigations, ERAF holding SM 130.

E. V. kaadriohvitseride saatus 1938–1994 (The fate of career military officers of the Republic of Estonia 1938–19944). Compiled by Vello Salo. Maarjamaa, Brampton, 1994.

Eesti rahvastikukaotused II/1. Saksa okupatsioon 1941–1944 : Hukatud ja vangistuses surnud = Estonian Population Losses, vol. II/1. German Occupation 1941–1944 : Victims Who Were Executed and Those Who Perished in Imprisonment, compiled by Indrek Paavle. Okupatsioonide Repressiivpoliitika Uurimise Riiklik Komisjon (Estonian State Commission on Examination of the Policies of Repression), vol. 17, Tartu, 2002.

Lõhmus, Leho. Nõmme eliidi saatusest (About the fate of the elite of Nõmme). L. Lõhmus, Nõmme, 1997.

Nõukogude okupatsioonivõimu poliitilised arreteerimised Eestis. 2. köide (Political arrests in Estonia under Soviet occupation. Vol. 2). In series: Represseeritud isikute registrid, 2. raamat (Repressed persons records, Book 2). Compiled by Leo Õispuu. ERRB, Tallinn, 1998.

Peeter Kaasik, „Disbanding of the Estonian and Military Establishments,“ Estonia 1940–1945: Reports of the Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity (Tallinn: Inimsusevastaste Kuritegude Uurimise Eesti Sihtasutus, 2006).

Poliitilised arreteerimised Eestis 1940–1988. 1. köide (Political arrests in Estonia 1940–1988. Vol. 1). In series: Represseeritud isikute registrid, 1. raamat (Repressed persons records, Book 1). Compiled and edited by Leo Õispuu. ERRB, Tallinn, 1996.

Punane terror (The red terror). Compiled by Mart Laar and Jaan Tross. Välis-Eesti & EMP, Stockholm, 1996.

Varju, Peep. Eesti poliitilise eliidi saatusest. 1 (About the fate of Estonia’s political elite. 1). In series: Publications of Estonian State Commission on Examination of the Policies of Repression, vol. 1. ORURK, Tallinn, 1994.