The Deportation of Germans from Estonia: A Unique Diary Sheds Light on a Forgotten Crime

The Estonian Institute of Historical Memory has published a book that sheds light on the story of the deportation of Germans from Estonia, told from the perspective of a modest accountant who fell victim to this tragic event. The diary entries offer fresh insights into Soviet repressions and illuminate the role of Baltic Germans, a group that has been largely overlooked in Estonian history.

The following article has been published with permission from Postimees.ee.

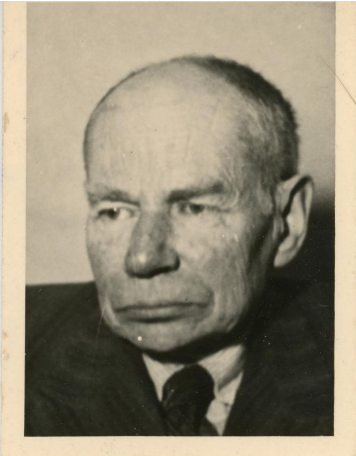

Georg Heitman was one of 407 Germans who were deported from Estonia in 1945. Could you explain why we know so little about this deportation?

One of the reasons for this is that Estonian memory culture is strongly connected to the deportations of Estonians. These deportations occurred twice and on a much larger scale, leaving a lasting impact on the collective memory of many individuals and their descendants, who remain closely associated with these events. The deportation of Germans is unfamiliar to us. The individuals who survived the deportation and their descendants, who still live here, are no longer Germans.

But those deported Germans were mostly Estonian citizens. Many of them also spoke Estonian.

That is true, but later on, they started feeling ashamed of being deported as Germans. Being a German in the Soviet Union after World War II was twice as bad as being an Estonian. One illuminating part of the book is the author's explanation that in remote areas of Russia, no distinction was made between an Estonian and a German - both were considered fascists. But in certain regions where German culture had once thrived, it seemed to most people that the bad person, the exploiter, had still been a German.

Since Germans were deported from Estonia after the end of the war, once the threat they posed to the Soviet Union had disappeared, can it be regarded as an act of vengeance?

Yes, it was an attempt to get rid of people belonging to an enemy nationality. From a legal perspective, this could be interpreted as an act of genocide.

Did a genocide against the Germans occur in Estonia?

In the Soviet Union. One group of people was declared hostile and was gradually destroyed while being forcibly re-located far away from their homeland. Either in forced labor or exile. The primary cause for this was undoubtedly the war that started in 1941. For some reason, it took this long; the operation was only carried out in August 1945 when the war had already come to a complete end, and the Germans no longer posed even the slightest threat to the Russians.

Do we have a general idea of the approximate number of Germans who remained in Estonia following the Stalinist repressions?

I don't know the exact number, but I think several hundred. And mostly in rural areas. Of course, they could have already become culturally Estonianized by this point. Georg Heitmann was an accountant who lived and worked in Hiiumaa and before that in Petersburg. He spoke fluent Russian.

How did historians acquire the personal diary of this individual?

Since my time as an undergraduate student, I have maintained a strong interest in stories about Germans. I have not wanted to glorify any national group, and I'm not doing this research for that purpose. However, given that Germans have often been regarded as the cause of slavery in our history, I aim to make this image more scientific and objective. That's where my interest stems from.

Snippets taken from Georg Heitman's diary

Arrival at the destination in Russia: Sunday, August 26, 1945

Upon reaching the destination assigned to us for quarantine (Chernushka), the water was too shallow for docking, and all the baggage had to be transported to dry land on shoulders and using a small boat that couldn't approach the shoreline. I had to remove my shoes and socks and walk to the beach.

We climbed up the hill and saw a small settlement consisting of a few farmsteads. We spent the night in one of them, but before that, we visited a tiny sauna. We went from the sauna to the office of the female doctor to verify our identities. I was asked to provide my last name, first name, father's name, age, and specialty, and that was the entire identification process. Leaving the doctor's office, we headed towards a small house where we received lunch ration cards and bread. Then we went to the canteen, where we were served delicious soup and barley porridge.

How did Heitmann's diary make its way to the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory?

The Institute has an effective tool, namely the Memorial for Victims of Communism and an e-Memorial. Many individuals are highly interested in their repressed relatives: they provide specific details, submit additional documents, and offer hints about someone's fate. The descendants of Heitmann discovered that their names - both first and last names - were mostly erroneously written. They sent an inquiry. Subsequent communication revealed that they have interesting materials about their grandfather: a fully preserved diary from the years 1945-1947.

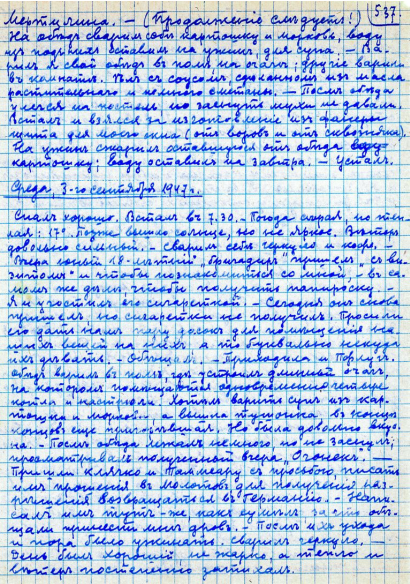

Where did he keep his diary, and what does it look like?

He began writing it while travelling to Russia. On the day of his deportation, when he was taken away from here, he was likely so shocked that he didn't write anything down yet. Heitmann started writing on the train and maintained a diary throughout the entire period of exile. The entries were recorded on a daily basis. Often, they were remarkably detailed, encompassing events, thoughts, dreams, and all physical activities, although the latter type of accounts were rare.

Was he only in exile or also in a prison camp?

In prison camps as well. However, what made his story truly fascinating and engaging was the final part of the diary—the escape to Estonia. A seventy-year-old man managed to flee and return home. At the time, his age alone was noteworthy, but he also had around ten different health issues. Undoubtedly, this part of the diary is a true thriller.

Snippets taken from Georg Heitman's diary

The dream of escaping to Estonia: Wednesday, August 27, 1947

On the last postcard, Lilja [Jelizaveta Heitmann] wrote about some kind of "combination," "venture." The thought of it troubles me - what is she undertaking? She wrote about it on August 7, and three weeks have passed since then – and nothing has been seen or heard since. Does it mean that nothing came out of the "combination"? – I have become so nervous that I see my close ones everywhere and wait for their arrival. If an airplane flies by – I jump up and look to see if it doesn't land near us. – Whenever I notice a person in the distance, especially a woman, I impatiently await their approach to find out if someone has followed me here. – Even when I'm alone at home and hear a knock on the door, I immediately jump up, pondering if it could be Lilja. – However, when I think rationally, I realize I wouldn't want Lilja to come here either - the journey is too difficult.

Why did he undertake such a life-threatening escape?

It runs through many entries in the diary. He was not born an aristocrat; his father was a brewer, and his mother was a homemaker. Their family was not wealthy, but in St. Petersburg, he worked his way up and became the chief accountant at the Treugolnik factory. He found himself among relatively educated individuals in the city.

While being forcefully relocated, he ended up in a Russian village situated alongside the Kama River. In this village, a significant number of inhabitants were illiterate, and there was dirt, resignation, and a lack of interest in working; he describes the large drinking parties there. Heitmann recounts his endeavours to learn the local Russian language, as he had never encountered the commonly spoken language used by ordinary people before. The life there appeared so depressing to him that he decided he didn't want to die in that environment. The Baltic Germans around him, fellow deportation victims, were constantly dying. They were not helped by their homeland, had no money or food, and were also in poor health. Many of them had lost hope to ever return to their homeland.

Snippets taken from Georg Heitman's diary

Rumors! Monday, March 25th, 1946.

There are currently several rumors going around about the potential of us returning to our homeland, and numerous factors contribute to the believability of these rumors. For instance, it seems that in the post office in Tallinn, they do not accept cash or parcels for sending to our address. Even more, local authorities are displaying heightened attentiveness towards us. They make an extra effort to maintain cleanliness in the barracks. Whenever someone falls ill, they promptly call for a doctor or medical attendant. In cases of severe illness, individuals are being considered for transfer to Saigatkas, where they place them into the hospital. – There are widespread rumors circulating that Stalin has been removed from power and that the People's Commissars have been renamed as ministers, indicating that our political framework is increasingly resembling the Western system.

Was his wish solely to die at home?

Yes, because his spouse, child, grandchild - they were all left behind in Estonia. He came back.

His wife came with her new spouse to pick him up; they helped to arrange things. However, it wasn't as simple as just walking back to his homeland. Of course, he did everything to prepare for the escape.

After escaping to Tallinn, he was ultimately arrested. What awaited him thereafter?

Yes, he was arrested. By that time, he had already become disabled. He had chosen to isolate himself indoors, keeping the curtains closed, from 1947 until March 1949, with the intention of avoiding detection by anyone.

After being arrested, Heitmann was taken to Patarei Prison and sentenced to 20 years of forced labor for illegally leaving the settlement. He was then sent to a labor camp, but a few years later, he was transferred to a closed nursing home or colony, which is a closed hospital-type facility.

Snippets taken from Georg Heitman's diary

On Suffering and Alms. Wednesday, October 16, 1946

A partially sighted beggar came to our place and asked for a donation in the name of Christ, but nobody offered anything. We explained that we were beggars ourselves, sent here in exile, and suggested that the beggar seek help from the Russians, the peasants. – We are cold and ruthless, all of us! – When he left, I felt an urge to follow him and give him something, but I hesitated. – Shame, you wretched servant of God, Georg! There's a possibility that you might end up being sent, if not to the Russians, then to the Germans, Estonians, or even to hell. – Oh, Georg, Georg, it is true that you possess very little, but you are not yet starving, even though living in warmth remains a distant dream. Shame on you!

Did he give up writing after the second arrest?

He no longer kept a diary, but he wrote a significant number of letters, many of which have been lost. However, a few of his later letters have managed to survive.

How was he able to find enough paper to write so much, given that there was such a severe shortage? And how did he manage to prevent the soldier or officer who was inspecting him from taking it away and not giving him an additional five years for its contents?

Initially, the entries are quite neutral, with a significant amount of information about where the train traveled and arrived, what was eaten, the outdoor temperature, and who spoke with whom. However, in the subsequent parts of the diary, an increasing number of remarks come to light, highlighting carelessness, the indifference of the Russians, and the brutality of the officials - not physical brutality, but rather psychological terror and so on.

If the papers had ended up in the hands of the overseer, it would have caused big trouble. Why his story didn't come out is unclear, but it's possible that the locals weren't interested in a seventy-year-old man. They either awaited his death or hoped for his disappearance from the area. When he escaped in 1947, the locals made no attempts to stop him.

As for paper availability, it is known that Heitmann, being a pedantic bookkeeper by nature, took great care to bring along as many items as possible to the settlement. For instance, he took his wife's suitcase, fearing the possibility of her being forced to leave as well. Eventually, Heitmann started exchanging his wife's clothing for notebooks. One of the most interesting parts of the diary is the description of living conditions in Russia. Far from living in grand public buildings, they had to rent for their scarce money, which was sent from their homes, a crumbling barrack with a fireplace that posed a fire risk, windows that either let drafts in or had no glass at all.

Heitmann himself lived in a barrack that belonged to a local person, who himself lived in another corner of the room. Heitmann describes a situation where the house owner pulls out sheets from his notebook to give to him because the diarist has run out of paper, saying, "But I don't want to write, I have no interest in it. You take it!"

How does Heitmann describe his cultural self-awareness as an Estonian and a German? Does he even touch upon this topic?

This is a very important question. While he demonstrates a clear understanding of the German and Russian cultural spheres, Estonian culture remains entirely unfamiliar to him. His descendants have mentioned that Heitmann understood the Estonian language but did not want to use it. In his diary, he mentions that he cannot write in Estonian correctly, or at least he feels that he makes mistakes in it.

Georg Heitmann's cultural background was German-Russian, but one anecdotal part of his diary is an entry where he sympathizes with Estonians because Russians insult them by calling them Estonian fascists, and they respond by saying they are not Estonians but Germans. For ordinary Russian villagers, nationality held little significance. Instead, they would have inquired, "Where are you from?" From Estonia - therefore, Estonians.

It is evident that labeling Estonians as "fascists, Nazis, Hitlerites" is unjust. Heitmann, who possesses a deep sense of German identity, also acknowledges the historical guilt that Germans bear towards the Russians. The hero of this story has a great respect for Russian culture and Russian people, which is surprising considering he suffers unjustly at their hands.

Snippets taken from Georg Heitman's diary

Comparing prison and unbearable living conditions in exile. - Monday, April 14, 1947

While lying in my bed, beneath the stove top above me I couldn't help but reflect that my life here differs very little from that of a prison: I am undoubtedly not free, I have to live in Melnichnaya, I have to live in a cramped hut, I have been deprived of all comforts. My life differs from that of a real prison in the sense that a real prison is probably more comfortable, affordable, and overall better than my own life: in prison, I was provided with ready-made food, but here I am burdened with the task of preparing my own food, which can at times become overwhelming for me. In prison, I would be sufficiently fed and for free, but here I often go hungry, and my food costs a lot of money for my family. In prison, a doctor looks after my health - here, no one cares whether I'm healthy or sick; I broke my leg, I had to take care of it myself as best I could – in prison, medication is provided if needed - here, there are no medicines or resources for my heart, stomach, kidneys, bladder, etc. – everything has to be sent by my family from Estonia; in prison, there is a chance to get some fresh air every day, to move around, to walk in the yard —here, the mud and moisture are such that you can't take a step outside;—in prison—during winter, it's heated and you don't have to freeze—here, heating during winter comes with significant costs and overwhelming work, and yet you can still freeze to death, and no one cares, it doesn't matter to anyone if you're alive or not;—in prison—loneliness and silence—here, noise and clamor, but solitude and silence can be found as a rare bliss. – I am talking about solitary confinement – in community cells it is probably much worse, but still not worse than in the barracks and dormitories here, which I have unfortunately had to become more familiar with than I would have liked.

The book has 486 pages without index. This is a significant work that has been done over the past two years, involving a lot of effort and many working hours. Why is this topic so important in researching Estonian contemporary history?

The diary is important in several ways. It may be hard to believe, but sources such as diaries of individuals sent into exile - there are almost none of them in Estonia. There are a few of them from 1941. About ten years ago, Erna Nagel's diary was published, which even historians have forgotten. Furthermore, while there are a few scattered entries here and there, there simply hasn't been a diary that covers, for example, two years of a person's life in Siberia. Of course, many letters have been preserved because after the war, it became possible to send letters to Estonia. During the war, that opportunity did not exist.

Does this mean that in the context of raising awareness about deportations, this diary is unique?

In the context of Estonia, it is undoubtedly unique. It allows us to see Germans as our compatriots. They lived in our Estonian homeland and similarly suffered, being victims of Stalinist repressions. Their story matters too. The deportation is not just the story of Estonian-speaking people, but the story of all people who lived in this land, even though in this case, it is a rather sad story.