Contested Monuments in Post-Communist countries: Problems and Lessons

Although it is generally believed that most former communist countries removed their Soviet-era monuments soon after the fall of communism, many such monuments continue to cause controversy. What are the contested monuments? How do they address the issue of communist heritage in different post-communist countries?

Monuments and memorials exist in many different forms, but what is common among them is that they have both commemorative and political functions. They define what and who is to be remembered from the past - as well as what and who is not. As such, they convey the historical narratives preferred by those who erect them while, wittingly or unwittingly, concealing others. National elites are aware of the power of monuments and use them as tools to legitimate their political power and set social dynamics of inclusion and exclusion. However, the meanings of monuments are never fixed once and for all, as they reflect changes in culture, social relations, conceptions of nation, and views on the past.

Over time, individuals can interpret monuments in ways that are different or even contrary to the original intentions of the elite. Thus, monuments that once legitimised elite power can unexpectedly turn into sites of controversy and resistant political practice. Monuments then become controversial when they represent historical narratives and cultural values that society, or at least part of society, defines as outdated. Contested monuments often reflect the ideology of a bygone regime or carry traumatic memories. For this reason, their permanence in the public space becomes problematic.

Contested monuments in post-communist countries

There is a widespread perception that post-communist countries removed most Soviet-era monuments soon after the collapse of communism. This claim is exaggerated, as many are still standing today. This is the case especially for memorials, as to erase them is not an easy task for various reasons.

First, finding economic resources for removal was difficult during the transition to the market-based economy, and remains so today in time of crisis and austerity. Second, removing memorials that are still important in present-day Russian historical narratives can provoke fierce reactions by Russia, bringing consequences such as economic sanctions, diplomatic restrictions, and visa bans, as well as cyberattacks and hybrid threats. Third, Soviet memorials can still be important sites of commemoration for the Russian communities living in post-communist countries. Finally, removing remains from a memorial represents a sensitive issue for those affiliated with the Orthodox faith, which does not allow exhumation. For these reasons, there are several Soviet memorials still standing throughout the post-communist space.

Part of the population considers Soviet-era monuments a source of traumatic memories, associating them with the experience of the Soviet regimes, loss of national sovereignty, and deportation. For these reasons, post-communist elites have taken various measures to marginalise their visibility and, in turn their, ideological weight. Post-communist countries that joined the EU and NATO have availed adequate resources and sense of security to underpin the marginalisation of Soviet monuments, as well as to erect new ones reflecting the current needs of culture and society.

However, the marginalisation of Soviet monuments, or the erection of new ones, has not been widely accepted in post-communist countries, often sparking broad debates and even resulting in civil disorder. Here, multiple historical narratives and identities coexist at the societal level.

Post-communist countries have multi-ethnic societies consisting of two main ethnic communities: the main people ruling the country’s institutions (for example, Estonians, Ukrainians, and Kazakhs) and the ethnic-Russians, that is, Russian people and their descendants that found themselves living outside the territory of the current Russian Federation after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The relationship between these ethnic groups has often taken the form of an antagonism between an ethnic majority and minority populations. The potential divergences in historical narratives may be a likely explanation underpinning this antagonism, as they reflect two conflicting interpretations of World War 2 and its aftermath. This antagonism has often resulted in different or conflicting views on how monuments should be designed and redesigned.

Top-down strategies to deal with post-communist monuments

Elites across post-communist countries have used different measures to solve the issues of contested monuments, each one having its own symbolic, cultural, or political aims. The list below presents a typology of strategies to deal with Soviet monuments planned by national authorities in an official manner.

Leaving the monument as it stands

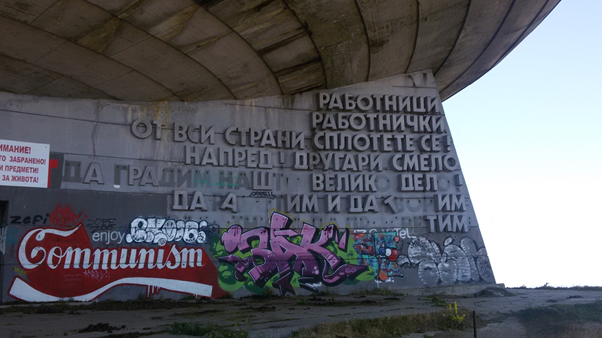

There are several Soviet monuments that are simply being ignored and left abandoned without any specific conservation plan. This is the case of memorial plates or smaller monuments in peripheral locations. However, also very visible monuments can be left abandoned, as is the case of the Buzludzha monument in Bulgaria - a spaceship-like structure building built between 1971 and 1984 to celebrate the Bulgarian communist party.

Abandoned monuments can attract unforeseen practices that interact with their original meanings. The Buzludzha monument is today a place popular among graffiti artists. In the picture below, one can see graffiti representing the word ‘Communism’ drawn as the Coca Cola logo (fig. 1). In some cases, such as the so-called “spomeniks” of the former Yugoslavia, abandoned monuments have unexpectedly gone viral on online blogs and become unusual tourist destinations.

Rewriting

Inscriptions and informative panels can be added or changed to create a new context to monuments. For example, in 2018 an explanatory text was added to the statue of Soviet Marshal Ivan Konev in Prague (fig. 2), stating that he was involved in the brutal suppression of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution and the Prague Spring of 1968. This text recontextualised the role of Ivan Konev in Czech historical narratives. This measure was highly criticized by Russia, leading to a deterioration of the relations between the Czech Republic and Russia.

Manipulating the surroundings

Manipulating the spatial surroundings can change the meanings of monuments. This practice has been broadly used to lessen the visibility of unwanted monuments. After the last Russian troops left Estonia in 1994, manipulations were carried out to reduce the visibility and soften the symbolism of the Bronze Soldier, a Soviet memorial removed in 2007 to a military cemetery outside the city centre of Tallinn (fig. 3): diagonal footpaths replaced the direct access, new trees were planted and the hollow for the eternal flame was removed[1].

Adding or removing elements

Adding or removing material elements to monuments may transform their meaning and function. Monuments can also be turned into something completely different by adding material layers. In Odessa, a statue of Lenin was turned into Darth Vader, a villain of the film series Star Wars. The Lenin statue was strikingly well-suited suited to the new subject: Lenin’s long coat became the cloak of Darth Vader, and his closed fist now holds a lightsaber.

In the video below, the Darth Vader was unveiled during an opening ceremony that included vehicles and characters from the Star Wars movies. Otherwise, removing elements is a common bottom-up practice to rejects the meanings of monuments: for example, in 2010 the statue of Josef Stalin in Zaporizhzhya, Ukraine, was decapitated as a protest by the right-wing nationalist organization Tryzub.

Relocating

Relocating monuments with site specific connections to the commemorated events and people can annihilate its original meanings. When a monument becomes controversial, it can be relocated to out-of-the-way destinations as an attempt to define its meanings as alien to today’s dominant culture. While relocation practices differ widely, parks and open-air museums accommodating fallen monuments are typical features of the post-communist city. Some examples are Fallen Monument Park in Moscow, Grūtas Park in Lithuania, Memento Park in Budapest, and Soviet Statue Graveyard in Tallinn. Originally aimed at reinterpreting a nation’s painful past through the display of its material remains, these parks have become attractive tourist destinations.

Removing and dismantling

Unwanted monuments can be completely removed from the public space and placed in storage, dumped in a hidden spot, or even dismantled. Dismantling monuments has often highlighted regime change, representing a firm statement to the people and ideals represented in them.

Some countries like Ukraine have recently passed laws to officially dismantle Soviet monuments at a national level. Soviet monuments were also spontaneously destroyed during the Euromaidan, a set of protests sparked in 2013 by the Ukrainian Government’s decision to suspend the signing of an association agreement with the EU (fig. 5).

Bottom-up strategies to deal with Soviet monuments

In parallel to top-down measures, there are several bottom up practices that contribute to culturally reinventing the controversial meanings of monuments. These practices can be collective, as with the excision of monuments during political protests, or individual acts, as artistic interventions aiming to reinvent the meanings of monuments. Along with the collective excision or the removal of elements seen above, defacing with paint is a common practice to reject unwanted Soviet monuments. This was the fate, for example, of the Bronze Soldier in Tallinn or the statue of Marshal Ivan Konev in Prague.

Art and creative practices such as graffiti, tags, murals, and wrapping are also used to exorcize the ghosts of a painful past and to creatively reinvent contested monuments. An interesting case is the Monument to the Soviet Army in Sofia, often painted to send out political messages: in 2011 a street artist painted over the memorial transforming the Soviet soldiers into pop culture characters (fig. 6). In 1992, the Liberty Statue in Budapest was wrapped in white to celebrate the withdrawal of Soviet troops: this performance helped to associate the Soviet monument with new meanings of freedom and independence. Less politicised practices also occur: for instance, flat grounds, sharp curbs, and pedestals around monuments are often used by skaters and bikers to try out their tricks.

Conclusions

Post-communist countries have variously dealt with the monuments and memorials inherited by the Soviet regimes. Each country copes differently when faced with monuments left over from the communist period, and bottom-up practices vary. However, there is a trend that is common to post-communist countries, as well as to post-totalitarian societies more broadly: to take initiatives to marginalise and remove Soviet monuments, while establishing new ones promoting the current needs of culture and society.

Contrary to the elites’ expectations, the measures taken to deal with old Soviet monuments - as well as the erection of new ones - have not been widely accepted in post-communist countries, where multiple historical narratives and identities coexist at the societal level. Monumental interventions have often sparked broad debates and even resulted in civil disorder. There is no single recipe or fixed formula to attenuate conflicts around contested monuments: each case has its own idiosyncrasies depending on social, political, and national context in which controversies emerge.

Federico Bellentani earned his PhD from Cardiff University. His research analyses the effects of monuments on social memory and urban identity, using Estonia as a case study. He lived in Estonia to conduct his fieldwork. In 2021, he published his first book on Estonian monuments. Today, he is Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of Turin, Italy.

List of sources.

[1] Ehala, Martin. 2009. The Bronze Soldier: Identity threat and maintenance in Estonia. Journal of Baltic Studies 1. 139–158.