Commemoration Day of the March 1949 Deportations: Terror through the eyes of a nine-year-old girl

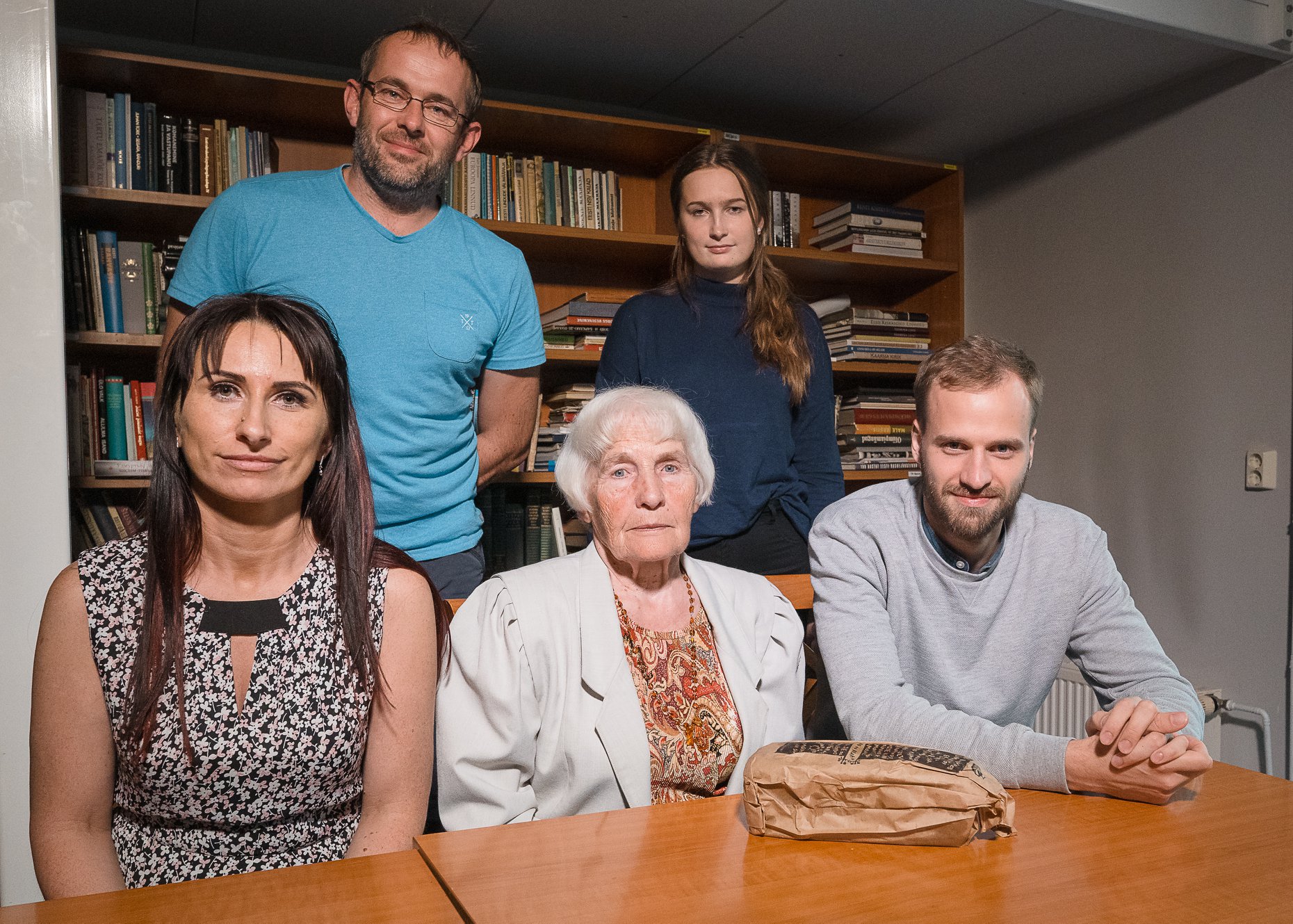

On the night of March 25, 1949, a deportation operation began during which more than 22,000 Estonians were deported to Siberia by the Soviet authorities. One of the deportees, Ellu-Eesi Uppin, recalls 73 years later how her family was deported and what life was like in Siberia.

"My mother had washed laundry in the late evening. She was exhausted, but she didn't go to bed. She sat behind a table and napped when our door was knocked on, and we were picked up," recalls Ellu-Eesi Uppin, who was only nine years old when she was deported from her hometown of Valga.

Her mother opened the door, and the deporters entered the room. The deportation decision was read out. They gave them about two hours to pack. My mother took a sewing machine to Siberia, which proved to be very useful in the following years. "It saved us from the extreme hunger that could have been without this sewing machine," she said.

Train

Ellu-Eesi, her mother, and her two sisters were put in a truck and taken to the Keeni railway station, where the family was forced to board a train. The head of the family was arrested around 1945 for alleged cooperation with the German authorities during the German occupation in Estonia (1941-1944).

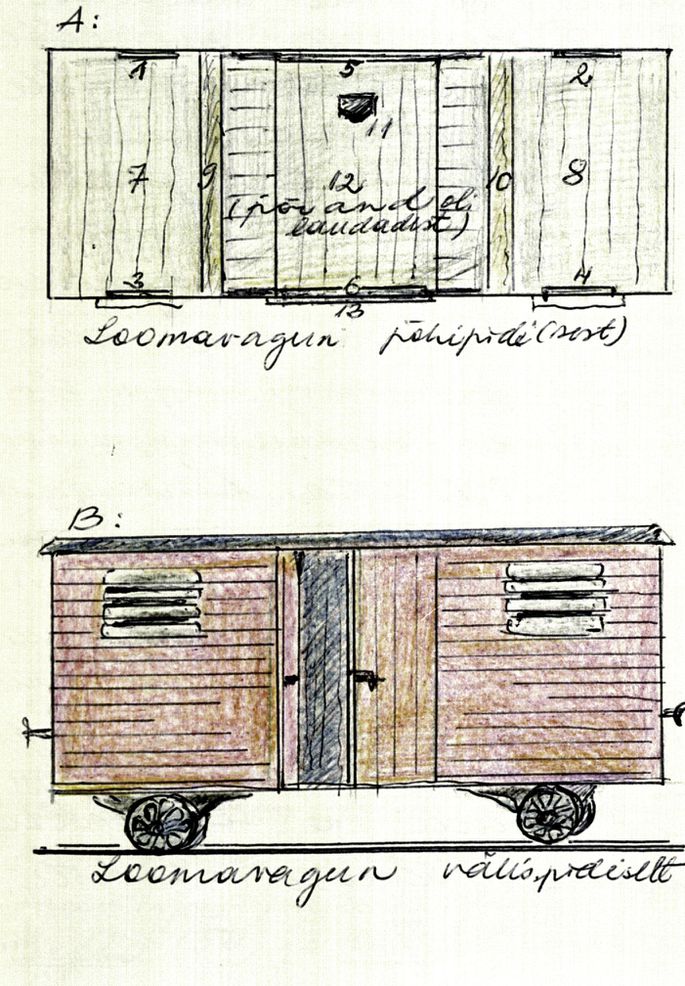

The journey by rail to the Novosibirsk region began. Ellu-Eesi recalls what the carriage looked like: "It was an ordinary cattle wagon with bunk beds and a small oven in the middle," she said. She remembers being allowed to go out during the train stops once a day, when they were given some soup. Many people died during the journey. "A newborn died in our carriage. Of course, the parents tried to hide the child's death because everyone who died was thrown out of the train," she recalls.

In Siberia

After the two-week journey, they arrived. People were driven out from the train. We had to stay outside in the cold for the whole night. “It was still wintery and snowy, although it was already April,” she remembers. In the morning, the horsemen with carriages came and took the people to the collective farms. Their family was taken to a collective farm located about 150 km from Novosibirsk. We moved into a house where we had to share a room with a whole family.

Estonians were treated well in Siberia, and relations with locals were good. “In general, the locals were very friendly and kind, but some were as vicious as anywhere,” she said.

A few years after, my mother bought a hut built of clay and manure. There was no water or toilet inside. The walls did not keep warm, and the floor was made of soil. Ellu-Eesi remembers well how the hut collapsed one year during the spring flood. The mother and her older sister had to rebuild their lodging. During this time, Ellu-Eesi had to work as a substitute for her mother in the collective farm.

Children did not usually have to work in Siberia, meaning she was able to go to school instead. But hunger forced her to work in the field of her collective farm with her sister during the summer. “We only went there to get a piece of bread for lunch,” she recalls.

Life on the collective farm was miserable. Because there were few machines, everything had to be done manually. “My mother had to work for a whole year. She had to work on weekends and holidays. They didn’t pay any money for work. She only received 20 kg of grain for a year of work. "Trying feeding four people with that!”

For three consecutive years, there was a very severe drought. This proved to be very difficult for the family. Until the fall of 1954, they did not get a good harvest. “All the while, I only dreamed that I could eat bread again one day,” she recalled of these harsh conditions.

Being away from home caused despair and longing. “Home was in our hearts all the time, and everyone was hoping that we could go back one day.”

Return to Estonia

A few weeks after Stalin's death, a decree on amnesty was issued, which also released Ellu-Eesi. The first amnesty also released children under the age of 13 at the time of deportation. Those who were older were not released. “My older sister had turned 13 in February, just before the March deportation. She was not released," she explained.

Ellu-Eesi was able to return to Estonia in 1954. However, her family had to remain in Siberia for years. After a 9-day journey by boat, car, and train, Ellu-Eesi finally arrived in Valga, where she lived in her aunt's house. "I was 15, but no one could believe I was that age," she said. The living conditions in Siberia had affected her appearance, making her look about five years younger.

The endless longing for home and the will to survive gave the rest of her family the strength to survive the long, harsh years of Siberia and return home later. “My sisters returned home in 1958, and mother in 1963,” she said. Her father survived extreme working conditions in a prison camp. He was allowed to join his family in 1956 in Siberia. In 1967, he finally had the opportunity to return to his homeland.