The Causes and Circumstances of the Outbreak of World War II

Polish historian Prof. Jan Rydel delves into the causes that led to the most tragic event of the 20th century, the outbreak of World War II.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the Soviet Union took steps in order to ensure the country’s full participation in international relations. It was an active and constructive participant in negotiations on the international Kellogg-Briand Pact (1928), the signatories of which renounced war as a tool of international policy (Treaty for Renunciation of War). Even before the Pact was set to enter into force, the 'Litvinov Protocol' was signed in Moscow in February 1929.

This agreement stipulated that the USSR and its western neighbours, including Poland, would immediately impliment the provisions of the Kellogg-Briand Pact, rather than wait until after the Pact's formal ratification. The Protocol paved the way towards an intensification of Polish-Soviet relations, which resulted in the signing of a non-aggression pact between Poland and the USSR on 25 July 1932. The European public was much surprised by the document, since Polish-German antagonism had been considered to be insurmountable. Thanks to the signing of the declaration, relations between Poland and Germany improved speedily.

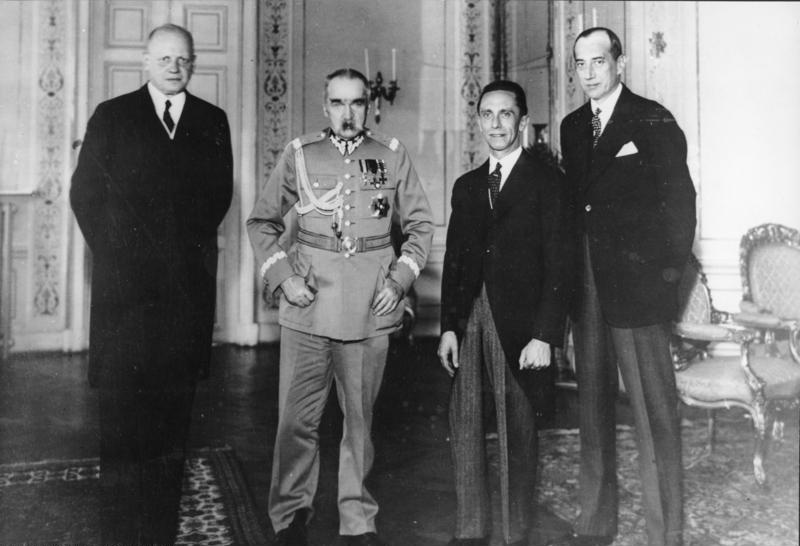

The initiative for these closer ties came mostly from Germany, which hoped to win Poland as an ally against the USSR. They were mistaken in this calculation. There was to be no joint planning of military operations against the Soviet Union, nor did Poland join the Anti-Comintern Pact (1936) despite the incentives offered to do so by Germany. The ruling group of Piłsudski supporters and the opposition rejected the ideology of National Socialism, and there were also no cooperation between Poland and Germany as regards discrimination of Jews.

Germany begins its expansion across Europe

In March 1935, Germany announced that it would not respect the arms restrictions imposed on it by the Treaty of Versailles (1919), which had ended the First World War (1914-1918) at great cost to Germany. This step did not meet with any real response from France, while Great Britain concluded a naval pact with Germany that sanctioned a considerable extension of the German navy. A year later, on March 7, 1936, German troops entered the Rhineland in a blatant violation of the Treaties of Versailles and Locarno. In the circumstances, Poland assured France yet again of its readiness to meet its obligations stemming from their alliance in case of a conflict with Germany. However, neither France nor any other western country, let alone the League of Nations, did anything more than issue purely verbal protests.

The political situation in Europe began to change radically when, in 1938, Germany triggered the implementation of its expansionist agenda and annexed Austria (March 12-13, 1938), forcibly seized Klaipeda from Lithuania (March 23, 1938) and, in particular, partitioned Czechoslovakia. During a conference in Munich (September 29-30, 1938), Czechoslovakia, although the most loyal ally of France, was pressed by its allies into ceding a vast borderland known as the Sudetenland, a strategically and economically important territory, to Germany. Although not a party to the conflict or participant of the Munich conference, Poland nevertheless forced crisis-ridden Czechoslovakia to cede Zaolzie (the part of Silesia beyond the Olza River populated mostly by Poles) to it.

Poland-Germany relations intensify

On October 24, 1938, the Polish envoy in Berlin Józef Lipski received a list of demands from the German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop intended as the basis for a new general arrangement of mutual relations between both countries. The German demands included the incorporation of the Free City of Gdańsk to the German Reich, the construction of an extraterritorial motorway and a railway link between East Prussia and the rest of the Reich, Poland’s joining the Anti-Comintern Pact, and permanent political consultations between Poland and Germany.

The objective behind the demands, extraordinarily moderate according to the Germans, was to force Poland to decide whether it supported Germany or not. Polish diplomats were greatly surprised by the German demands. For its part, Germany was astonished by Poland’s veiled, and later unambiguous refusal to accept them. The Polish Government treated Poland’s territorial integrity and sovereignty as inalienable. When interned in Romania in 1940, the Polish Foreign Minister Józef Beck did not mince words about the consequences of Poland’s hypothetical agreement:

We would have conquered Russia together with Germany and then we would have been grazing cows for Hitler in the Urals.

The resolution of that stage of the Polish-German dispute came as a result of the German seizure of territorially reduced Czechoslovakia on March 15, 1939. That move meant a violation of the relatively fresh Munich agreement as well as a crude exposure of the British and French appeasement policy. In response, Great Britain decided to give Poland security assurances on March 31, 1939, the basis for the British-Polish alliance. France also renewed its alliance with Poland. In response, on April 28, Adolf Hitler renounced the non-aggression pact with Poland, as well as the naval accord with Great Britain. On May 5, 1939, Józef Beck in a radio-broadcast definitively rejected the German demands. It was clear that Poland and Germany were on a collision course now.

The Signing of the Hitler-Stalin Pact

The events in Europe were closely followed by Joseph Stalin and Soviet diplomats. They were aware of their comfortable position, as they could choose which side of the escalating conflict to support and which one would assure them more benefits. Since April, talks had been going on in Moscow with representatives of Great Britain and France, yet no progress was being made. In actual fact, Stalin had already decided to change the paradigm of the Soviet foreign policy, i.e. initiate cooperation with Hitler. One obstacle to this was the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs Maxim Litvinov, a son and brother of rabbis from Białystok who distinguished himself as a staunch enemy of Nazism. On May 3, 1939, Litvinov was formally dismissed, and a purge took place among Soviet diplomats of Jewish origin.

Litvinov was now replaced by Stalin’s blind follower, Vyacheslav Molotov. Talks went full steam ahead in the last days of July 1939. Finally, Joachim von Ribbentrop flew to Moscow, and on the night of August 23-24 he negotiated a non-aggression pact with his Soviet partners. A more important and sensational part of the agreement was laid down in a secret protocol. It provided for a division of East-Central Europe between Germany and the Soviet Union, the sphere of influence of the latter including Finland, Estonia, Latvia and Bessarabia in Romania. As regards Poland, the Soviet Union additionally committed to invade it and occupy its eastern part up to the line marked by the rivers Narew, Vistula and San.

Thanks to the conscious action of an opposition-minded diplomat from the German embassy in Moscow, the content of the secret protocol was transmitted without delay to US, Italian and French diplomats. Even the Estonian government already had some information on this on August 26. The British had very incomplete knowledge about it but they sent it to Warsaw. Unfortunately, Polish minister Beck was most probably surrounded by Soviet agents of influence. As a result, he was not aware of the Kremlin’s changed course towards Germany and he also thought that after Stalin’s great purges the Soviet Union was unable to launch any large-scale operations. Consequently, he failed to grasp how precarious Poland’s position had become. His optimism was reinforced by the signing of a military alliance with Great Britain on 25 August 1939.

Germany invades Poland

Germany attacked Poland on September 1, 1939. On September 3, Great Britain and France declared war on Germany, which meant that one objective of the Polish foreign policy had been reached, that of not reducing the Polish-German war to a local conflict. Now, in compliance with the military agreements in force, the fighting Poles expected the allies to launch full-scale military operations within 15–16 days. Unfortunately, the allied commands concluded already on 4 September that they would not be able to effectively help Poland and that they would limit themselves to military demonstrations against Germany, focusing on preparations for future military action.

That decision was finally confirmed by a conference of French and British Prime Ministers accompanied by their highest-ranking commanders taking place in Abbeville on September 12, 1939. Those arrangements were not transmitted to Poland, as that could have broken its spirit of resistance. It is known now, however, that the information about the arrangements made in Abbeville were immediately transmitted to Soviet intelligence. In that way, the Soviets were assured that they could safely hit Poland from the east. In the morning of September 17, 1939, the Soviet army entered Polish territory. Despite Soviet assurances that the USSR was not involved in a war with Poland, bloody fights were taking place along the entire border, in some locations lasting until the first days of October 1939.

The fate of the Baltic states

The provisions of the secret protocol of August 23, 1939, and the defeat of Poland, which had been deceived by its allies, put Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania in a hopeless political and military situation overnight. Already on September 24, Molotov forced the Estonian delegation to agree that their country will be “integrated into the Soviet security system”, as stated. The Estonian-Soviet Mutual Aid Agreement was concluded on September 28 and the Soviet army entered the country. A week later (October 5), the same scenario was repeated in Latvia.

The fate of Lithuania was decided in a slightly different way. According to the provisions of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, this country was to enter the German sphere of influence. but, in September 1939, the Soviets expressed their intention to take Lithuania for themselves. For the sake of the newly formed alliance, the Germans agreed to the Soviets' request, and on September 28 both invaders concluded an agreement under which Lithuania was to be included in the Soviet zone, while the Soviets resigned from occupying Poland as far as the Vistula River, contented with the border on the Bug River.

Then, without delay, Lithuania was forced on October 10 to sign a cooperation agreement with the Soviets and to admit Soviet troops to its territory. On October 27, by the grace of the Soviets, the Lithuanian army entered Vilnius. On November 30, 1939, after unsuccessful attempts to intimidate Finland, the Soviets openly attacked the country, for what the Soviet Union was deprived of its membership in the League of Nations. Thanks to their heroic defence, the Finns managed to conclude a compromise peace in Moscow on March 13, 1940, under which they lost important territories and had to hand over some military bases to the Soviets but retained their sovereignty.

Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia were given no such chance at preserving their independence. After a wave of repressions and manipulations in the spring and summer of 1940, puppet governments have been installed in all three countries. The communist collaborators asked for their countries to join the Soviet Union, which occurred between August 3 and 6, 1940.

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, also known as the Stalin-Hitler Pact, paved the way for the latter’s attack on Poland, and for the illegal annexation of the sovereign Baltic states. Furthermore, the Pact guaranteed Hitler that, with no threat from the east, he would be able to de facto conquer or control the entirety of continental Europe, install his occupation regimes throughout it and execute the ‘final solution to the Jewish question’. Managed from Moscow, the Comintern ordered communist parties across the world to stop anti-fascist propaganda and change entirely the course towards Germany, now together with the Soviet Union making a ‘camp of global peace’.

Jan Rydel is a historian and his research areas are Central and Eastern Europe and Polish-German relations in the 19th and 20th centuries. He is the author of Politics of History in Federal Republic of Germany: Legacy – Ideas – Practice (2011) and Polish Occupation of North Western Germany, 1945–1948: an Unknown Chapter in Polish- German Relations (2000, German edition 2003). Until 2010 he was a researcher and a professor at Jagiellonian University and is currently a professor at the Pedagogical University of Cracow. Prof. Rydel is a Member of the ENRS Steering Committee and coordinates the Polish party in the European Network Remembrance and Solidarity (ENRS).