A Brief History of Italian Communism

After World War II, the Italian Communist Party (ICP) became one of the largest of its kind in Western Europe. At first, ICP maintained close ties with the Soviet Union, but a series of events transformed their relations in the following decades. Khrushchev's revelations of Stalin's crimes and Soviet military intervention in Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Afghanistan led to the gradual estrangement of Italian communists from the Soviet Union. In the 1970s, ICP adopted a theory of Eurocommunism.

The concept of communism in Italy may be associated with a variety of things. On one hand, Italian communist leaders, such as Enrico Berlinguer, are still today praised for their political skills and contributions to society even by those who support more right-wing lines of thought. On the other, some events remain controversial, like the murder of Christian Democracy leader, Aldo Moro, at the hands of the Red Brigades, a terrorist organization of communist inspiration.

The Italian Communist Party, widely known as PCI, was founded in 1921 in the Tuscanian town of Livorno following the secession from the Italian Socialist Party, and it eventually became the stronghold of Western communism. At the beginning of its history, the influence coming from the Bolsheviks – who had conquered power just a few years prior – was inevitably strong. The PCI was obviously part of the Comintern (and later of Cominform), and as such, aimed at implementing Lenin’s point of view on communism by trying to appeal to the local working class.

However, the two factions that caused the split in the Socialist Party stayed even within the PCI: the Ordine Nuovo (“New Order”), led by Antonio Gramsci and closer to the Bolshevik ideology, and the Massimalisti (“Maximalists”), led by Nicola Bombacci, amongst whose supporters we could once find Benito Mussolini – many of them, in fact, just a few years later joined the Fascist ranks.

However, while the Soviet influence was great and without the 1917 revolution, the PCI would not have existed in the first place, communism in Italy from the beginning acquired a more democratic face. Even from a dialectic point of view, Antonio Gramsci always avoided the phrase “dictatorship of the proletariat”, and preferred the arguably more peaceful “hegemony of the working class”, a gradual, non-violent process that would bring the working class – including professionals and technicians – to power.

The PCI, at least at first, maintained the “democratic centralism” advocated by Lenin, but never dwelt too much in ideology, and preferred to try and answer to the real needs of Italians, such as improving public services and strengthening the economy, as well as protecting the “fundamental freedoms of the citizens” who should have lived in a “democratic republic of workers [supported by] a representative parliamentary regime”, as the official Party program of 1946 stated.

World War II and ‘La Resistenza’

With Mussolini’s Fascist government, every other opposition party was outlawed – pretty significant in this aspect is the political assassination of Giacomo Matteotti, the socialist leader who, after a passionate speech denouncing Mussolini’s dictatorship in June 1924, was found dead just a few weeks later – and so was the PCI in 1926. However, its members continued to work underground. During these years, Antonio Gramsci ensured its position of power within the party, and after his arrest, this role passed on to Palmiro Togliatti.

The Italian Communist Party played a significant role in the Resistance Movement, whose activity intensified after the fall of Mussolini in 1943. At first, partisan formations were mostly comprised of a disorganized network of former officers of the Royal Italian Army, but later the Comitato di Liberazione Nazionale (CLN, “Committee of National Liberation”) was created as a cooperation between the Italian Communist Party, the Italian Socialist Party, the Partito d’Azione (“Party of Action”, a republican liberal socialist party), and Democrazia Cristiana (“Christian Democracy”, a more conservative party which later became the biggest antagonist of the PCI).

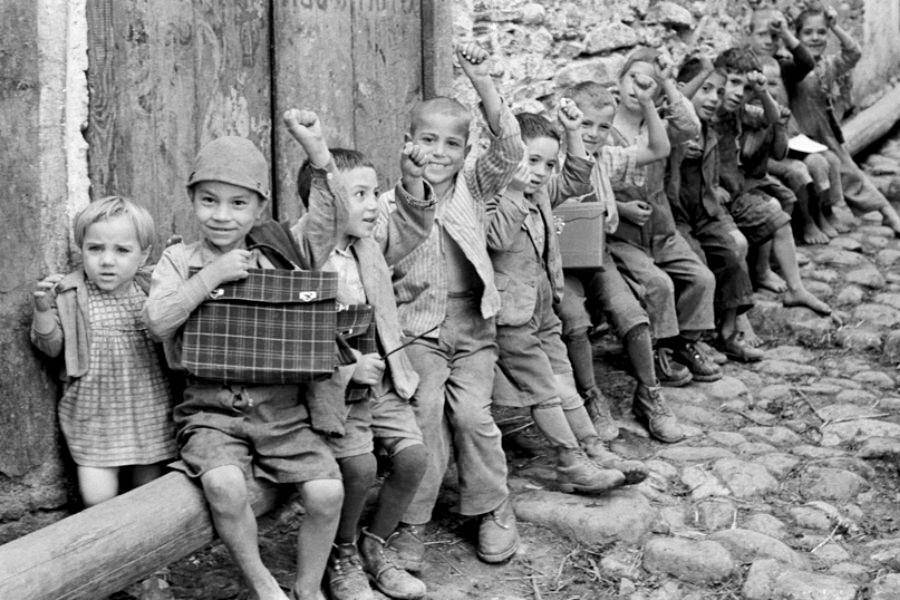

Partisan formations were very heterogeneous, and even if communists and socialists made up for the majority, as shown by the CLN composition, in the end, anyone who identified as anti-fascist – and thus even catholics, young students, and a minority of monarchists – actually joined the Resistance.

The PCI managed the so-called Brigate Garibaldi (“Garibaldi Brigades”), which made up for 41% of the total partisan forces (as of May 1944, between 70,000 and 80,000 individuals – by the end of the war, in April 1945, the number had increased to over 250,000 people), and they mostly operated in Northern Italy. Although most partisans were Italians, there was a strong component of international aid, especially of escaped prisoners of war from Yugoslavia and the Soviet republics, but also from other European countries like Spain and Greece, and from German deserters who became disillusioned with Nazism.

The partisans’ – and in a certain way, communists’ – contribution to the liberation of Italy is of undiscussed importance. The Italian constitution itself, which came into force in 1948, was written for a part by Italian communists, and, as aforementioned, it states that “Italy is a democracy based on work” (art. 1), and that “every reorganization, in any form, of the now-dissolved Fascist Party, is forbidden” (art. 13). We can also include the Legge Scelba, issued in 1952:

“there is a reorganization of the now-dissolved Fascist Party when an association or a movement pursuits anti-democratic goals inherent to the Fascist Party, exalting, menacing, or using violence as a political instrument, or advocating the suppression of the liberties guaranteed by the Constitution, or denigrating democracy, its institutions, and the values of the Resistance, or carrying out racist propaganda, that is it directs its activities at the exaltation of representatives, principles, facts and methods inherent to the aforementioned Party, or makes external displays of fascist character.”

In any case, while without the support of the communists, the war would have probably had a very different ending, the relationship between partisans and civilians may not always have been positive. The so-called ‘Foibe Massacres’ are an emblematic example of this, and to this day, remain a controversial topic. It refers to the mass killings of Italian civilians living in the regions of Friuli, Istria and Dalmatia, committed mostly by Yugoslav partisans, who later threw the bodies into natural sinkholes in the ground – the titular “foibas”. The motives of these killings are still unclear, but not surprising if put into the context of the war: many of the victims were Fascist sympathizers, while others were most likely just anti-communists or anti-Tito, or, according to some Italian historians, victims of ethnic cleansing as a revenge against the Italianization of Yugoslavia.

These events have been mostly instrumentalized by the Italian Right, by politicians like Silvio Berlusconi. However, after years of covering up, the Left too has recognized its culpability, first and foremost thanks to former President and Prime Minister Carlo Azeglio Ciampi, and Democratic leader Walter Veltroni in the 2000s.

After the War: A Communist Italy on the rise

If communist ideology was slightly put apart for a while during the war years in favor of a broader coalition that could defy Nazi-Fascism, soon enough, the Italian Communist Party continued to gain popularity amongst the people – mostly workers and farmers – and governmental power, and contributed in laying the foundations for the values of the newly-born Italian Republic.

Christian Democratic Prime Minister Alcide de Gasperi sent the PCI off into the opposition in 1947, fearing that the Left might surpass him, under the advice of US Secretary George Marshall, who supported even economically anti-communist sentiments in Italy, claiming anti-communism as a necessary pre-condition for receiving the aid of the Marshall Plan.

In the following years, after the “Marshall ban” ended, the Communist Party gained more and more success, especially in the regions of Tuscany, Emilia-Romagna, and Umbria, and became the only Western communist party, together with France, to join the Cominform. Under the guidance of communist hardline leader Palmiro Togliatti, its relations with foreign communist parties, especially with the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, intensified: after the Tito-Stalin split of 1948, in fact, the Italian Communist Party sided with the USSR and its relations with Yugoslavia loosened. It seems quite relevant to remember that AvtoVAZ, or the Lada factory, was set up in collaboration with the Italian FIAT in 1966, and the Russian town of Stavropol-on-Volga was renamed Tolyatti in honor of Togliatti after his death in 1964.

However, despite the ideological vicinity to Soviet communism, the Italian Communist Party maintained the capacity to operate efficiently, even if on a municipal level. In fact, as of 1975, the PCI was the leading force in the majority of Italy’s biggest cities, most importantly Bologna, called “The Red One” because of its uninterrupted history of communist leadership.

The 1950s, though, represented a turning point for Italian communism. First and foremost, the exposure of Stalin’s crimes by Khrushchev was a tough blow to all Party members and sympathizers. Communist Bruno Corbi stated that he and his comrades felt betrayed and wondered in what they had believed all along, when Stalin was just presented as the “father of the oppressed and defender of the humbles”, and no one – but maybe, it can be argued, Togliatti, who frequently visited the USSR and was very close with Stalin – knew about what he did.

Later, and probably most importantly, the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 created another split inside the PCI between those, like Togliatti, who saw the insurgents as “counter-revolutionaries”, and the others, like Giuseppe Di Vittorio and socialist ally of the PCI Pietro Nenni, who disagreed with the Soviet’s violent suppression of the revolt. This was but the first of a series of events that marked the gradual estrangement of Italian communists from the Soviet Union.

The Berlinguer-Brezhnev split

When the Soviet troops invaded Czechoslovakia in August 1968, the then PCI national secretary and later secretary-general Enrico Berlinguer strongly condemned the actions undertaken by Moscow. In direct contrast with the perpetual filo-soviet view of Togliatti’s communism, Berlinguer set the start to a new era in Italian politics, decisively shifting the newly independent character of Italian communism towards a more moderate and ‘Italian’ line of thought.

Berlinguer himself explained his new approach as a Terza Via (“Third Way”), an alternative type of socialism far both from the Soviet-type and from Western capitalism, a “socialism that we believe necessary and possible only in Italy", as he stated in 1976 in front of 5,000 communist delegates in Moscow, ultimately underlining the PCI’s autonomy with regards to the CPSU. Moving towards Eurocommunism and Socialist International, Berlinguer chose to trust NATO, and eventually negotiated the Compromesso Storico (“Historic Compromise”) with the long-time opponent of the PCI, the Christian Democrats, towards the end of the 1970s.

This was a particularly clever move which made of Berlinguer the most popular politician of its time, and increased, even more, the social support of the Italian Communist Party. In fact, the 1970s and 1980s in Italy are known as Anni di Piombo (“Years of Lead”), because of the numerous terrorist attacks that inundated the peninsula, both by far-right and far-left groups and a “united front” of the two leading Italian parties would have given more stability to the people. However, the aforementioned murder of Aldo Moro at the hands of the ultra-left terrorist group Red Brigades (who were supported by the Czechoslovak State Security) stopped the negotiations, and from this point onwards, the PCI’s influence started to decrease.

The End of the PCI

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the Martial Law that was instituted in Poland were two other factors that made the gap between the PCI and the CPSU even deeper. In fact, even if Moscow kept sending finances to Italian communists even during the progressive estrangement initiated by Berlinguer, in 1984 it stopped altogether.

In 1989, when Eastern European communisms were all on the verge of the collapse, the PCI acknowledged the failure of international communism during the new leader Achille Occhetto’s speech known as the Svolta della Bolognina (“Bolognina Turning Point”). Eurocommunism had come to a halt, and the Communist Party of Italy was dissolved and then refounded under the name of the Democratic Party of the Left, a progressive left-wing democratic socialist party. From that moment, more and more splits and divisions happened within the former PCI members, with more and more leftist or center-leftist parties coming out. However, not one of these parties could get a grasp on the Italian population, as the Italian Communist Party did.

Italy tried its experiment with communism, and it is not sure whether it was a success or a failure. What can be noted, though, is that the Party did a good job on the municipal level, gaining a great deal of popularity among the people, especially thanks to the role it played in the Resistance and during the era of Enrico Berlinguer.

It is though important to understand two things: first, the magnitude of the events that happened in the Soviet area of influence (the Hungarian Revolution, the Prague Spring, and so on) was never apparent to the outside countries, and maybe people never fully understood what happened inside what they thought was the greatest anti-capitalist power; second, Italian communists, even under the more orthodox guidance of Antonio Gramsci and Palmiro Togliatti, always emphasized the need for democracy and “polycentrism”, that is, the need for each country to find one’s own way to socialism.

Of course, this was possible because communism in Italy was not ideologically pervasive and imposed from the top, as it happened in the USSR, but was just one of the alternatives proposed to Italians. However, there is a question that Italians of any political view ask themselves: what would have happened if Italy could not distance itself from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union?

Sources and literature

Alvin, Shuster, Communism, Italian Style. New York Times Magazine. May 9, 1976.

Partito Comunista Italiano, Wikipedia, October 9, 2020.

Partito Comunista Italiano PCI - Il sito ufficiale del Partito Comunista Italiano. October 9, 2020.

Resistenza italiana, Wikipedia, October 9, 2020.

Andrea Varriale, The myth of the Italian resistance movement (1943-1945): the case of Naples. In: Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte, 27, 2/2014, pp. 383-393

Pci e Urss legami pericolosi - - la Repubblica.it. October 9, 2020.

Silvio Pons, L'Italia e il Pci nella politica estera dell'Urss di Breznev, in “Studi Storici”, a. 42,. 2001, n. 4, pp. 929-951

Il Partito Comunista Italiano e l'Unione Sovietica, brianzapopolare.it. October 9, 2020.