Ballad of Siberia: Photographs of the daily life of Estonian deportees

The unique photographs of Vello Hindreus (1930–2020) capture the life and nature of Siberia during the years when thousands of Estonian deportees had to fight for their survival in remote parts of Russia. His photographs give us a more profound understanding of the lives of deportees than other photo collection known so far. Only a few such collections have survived to this day.

Vello Hindreus was born on May 13, 1930, in Tallinn. He was the first child of his father, Egon-Ferdinand, and mother, Anette-Adele. Later, his brothers, Ilo and Hands, and sister, Lii, were born into the family. Vello's father fought both in the First World War and the Estonian War of Independence. After the wars, he worked as a border guard in Hiiumaa, and later as an electrician in Tallinn.

In 1944, Vello's father and brother Ilo were arrested by Soviet authorities. They were determined to be ‘socially dangerous’ individuals by the newly-established communist regime in Estonia due to Egon-Ferdinand’s former membership of the Estonian Defense Forces and Ilo’s having voluntarily served in the German Defense Forces. Vello’s brother Hans fled to Finland, saving himself from mobilization, and served in the Finnish Navy. After the war, he started a new life in California.

A relative of the "enemies of the people" was not allowed to work at sea

The fate of his father and brothers directly affected Vello's life. At first, he was not permitted to enter nautical school because of the anti-Soviet behavior of his family members. Instead of that, he enrolled in the Nõmme projectionist school. It was a two-year course. He became a first category stationary and mobile cinema projectionist.

After graduating from school, Vello worked at the October theater in Tallinn's Old Town. Even recently, he was able to recall many films of that time. He especially remembered the propaganda film ‘Ballad of Siberia’. It showed post-war Siberia and praised its good life. The central themes of the story were the self-determination of a young man in the middle of Siberian nature and people, the emergence of factories and settlements in primeval forests, and the eternal struggle of man and nature. By an irony of faith, Vello soon had the opportunity to tell his story about Siberia because, after the deportations in March 1949, he was one of the thousands of Estonians who were deported.

The journey to Siberia started from Tallinn Ülemiste railway station and ended in Son Khakassia

“It was Saturday. I went to the sauna. The Nõmme sauna on Valdeku street. I went to the sauna and put the dirty laundry in my briefcase. Got two pounds of sugar at the store. My old classmate invited me to his place. He lived in an apartment somewhere in Nõmme. He knew the woman who owned the apartment. She worked for the Nõmme executive committee.

He met with her and said: “Vello is coming to visit me tonight.” We met there that night. There were several guys for some reason. As if we were hiding. A Russian navy officer and two soldiers came to get us at night. Everyone was taken to the Nõmme police station. We were jailed and interrogated. The rest were released. I guess they weren’t on the list. I was the only one. They kept me there until the morning. A truck arrived and I got in. I was completely alone. I don’t recall if there was a soldier guarding me. I was taken to Ülemiste Station. They put me on the train. Some people were already sitting inside. The soldiers had gone to the cinema and theatre. They told people that I had been arrested and taken away. Probably my colleagues had gathered some things for me. My bedding, I think. They brought them to the railway station. I had nothing. I left the sauna with my briefcase of dirty laundry. Some clothing that I had in the basement. They wrote a letter. When you arrive, send your address to the movie theatre. They mailed me my salary and vacation pay.”

“I wasn’t afraid. I was indignant. Depressed. What’s going on? What does this mean? There were rumors for some time that people were being arrested. The manhunt had been going on for three days. I don’t know. I just felt depressed. What’s going on here?”

“The train took us to the Urals, but I don’t remember if the windows were ever opened. There were long stops. The train crossed the Urals, and we reached cities like Omsk and Novosibirsk. The station was called Son, in the Khakas Autonomous Oblast.”

Arrival

In Siberia, he met with his future wife Elli Siitan, who was also deported (the marriage was contracted in 1954).“At first, I didn't know if the deported person could get married there at all. But it turned out that this was not a problem at all. We started living together. We were expecting to have our son Heiki. He was the first one. He was born in 1954. Two more sons were born later. Elmar and Vello. Since we had to choose a name for the child, I had to go to the village council. The son was born on March 27. It was precisely the same day I was deported. On April 4, I went to the village council. My wife was at home. The head of the village council said: "It is necessary to get married first." He was a fine man at the time. When we first came there in 1949, the same man had called us fascists. I even sold him my pocket watch.”

“We will not allow you to name your child until you are married. So the Secretary of the council wrote everything down. The name of the mother and father, place of birth, etc. Then they issued a marriage certificate. The marriage was contracted. You were then allowed to name your child. We didn't have a party.”

“Our family lived together in a wooden shack. We had only one room. There were our bunk beds, a large Russian oven. We prepared food on it. Our house had only two windows.”

Taking photos

Vello had a camera in Siberia. The family has preserved several hundred pictures of Siberian nature, the daily life, and the living conditions of the deportees.

“I had a camera, but I do not remember if they [collegues from the movie theatre] gave it to me with my things. I must have had one since I took pictures at the movie theatre. I do not know if the camera was mailed to me. It was either a Komsomolets or a Lubitel. They were similar. The image was 6x6 cm—wide film. I do not remember how I got the camera. I must have gotten one somehow. I used up one roll of film that summer, but I couldn’t do anything with it. What can you do with the film if you don’t have supplies? No chemicals, not to mention other items. I’m not sure, but I wrote letters to my mother. Perhaps she sent me film. Where did I get a developer or fixer? Later, it wasn’t a problem. Life got better. After Stalin’s death, they started developing virgin land. A big new sovkhoz [a farm owned by the Soviet state] was built. There were lots of goods. You could buy anything. The film became available. I bought a second camera called a Moscow. It was 6x9 cm. I didn’t really need a new one. Since I had the camera, I wanted to photograph how we lived there. The main subjects were my family. And village life, of course. The people who had been deported with us. We celebrated our summer holidays. We left the village together. The landscape was mountainous, and there weren’t many forests. I took pictures of people at work. Whenever I took photos, everyone wanted one. But I didn’t take pictures to make money. That was out of the question. Everyone wanted photos. I even took pictures of the locals. “Dear Vello, please take a picture of me.” So I took photos of them too. Sometimes they paid me a little. I do not remember. Maybe they gave food, eggs, or something. It wasn’t a problem. Of course, I took photos of them.”

“But I didn’t want to waste the film. I tried to be as economical as possible. There was nothing written on the back. Not even the year. I don’t know why. There was no electricity in the village. That was the worst. I made my own equipment with a lamp. An ordinary kerosene lamp, which I placed in a box. I got some red glass. Otherwise, you couldn’t see. The red glass covered the lamp. The lights shone through. I had acquired developing tanks. I don’t know where I got those. You put the film inside. There are two halves with grooves. The grooves hold the film evenly spaced. You put it and close the tank. Pour in the developer. When you’re done, you pour out the developer and rinse. You have to rinse, then pour in the fixer. After a while, you can see if anything came out if you got a picture. I bought a Moscow camera. 6x9 cm. The images were larger, but you had fewer frames per film. I think there were 16 frames. I thought: “This is no good.” So I modified the camera. I cut some pieces of sheet metal and combined them to get 6x4.5 cm images. In other words, I cut the 9 in half with a frame that went inside the camera. And for the viewfinder, of course. I think I made another smaller framer for it, so that I could see the correct image. I got more photos that way, and it paid off later. I was able to enlarge them back in Estonia.”

With his wife and three sons, Vello returned to his homeland on April 15, 1957. “You had to accept the life you were given. It wasn’t your life. It was directed by someone else. Someone decided for you.” Vello died in 2020.

Marko Poolamets (operator and photographer of the portal Collect Our Story) comments on how he first met with Vello’s photos:

“In September 2019, we recorded an interview with Vello for the oral history portal Collect Our Story. Vello's son Heikki showed us some pictures his father took in Siberia. At first glance, it was clear that these pictures are very unique. His photographs give us a more profound understanding of the life of deportees than other photo collection known so far. Only a few such collections have survived to this day.”

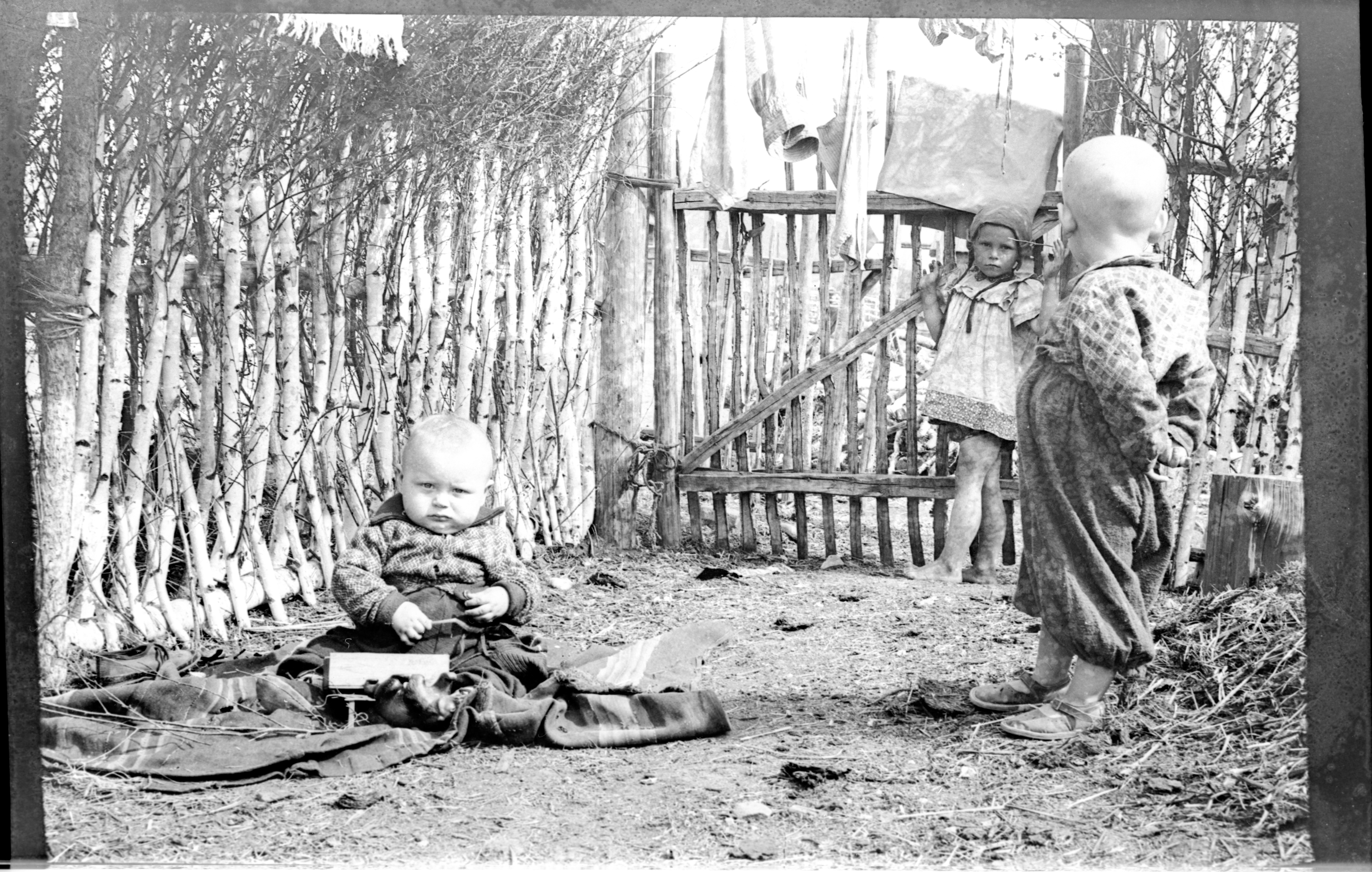

“Vello mainly made portraits. But the pictures also reflect the daily life, landscape, nature, and village environment. He has taken shots of local people, local village life, funerals, family events, and the gathering of deportees. There are also a number of class pictures where local students are mixed with deported students.”

“Vello also took photos of local families. These are fascinating and very informative pictures. The local families had different traditions and habits. Everything is reflected in the pictures.”

“On the one hand, people seem to be in the foreground of these photos. On the other hand, they are secondary and do not interfere. These images contain so much new information that we can't get anywhere else. Even the group photos are very informative. They contain more details than we normally expect from such images.”

The material deprivation of deportees is reflected in those images. At the same time, we can see how their standard of living improves over time – people later build new houses, own motorcycles, and so on. There are also some pictures of the interior of the houses. These confirm the oral information we had about the whitewashed walls. It also confirmed that mainly the outwear was brought along from home. Only a very few items could be seen on those images. When one looks at those photos, a rather odd paradox arises. Everything is miserable and poor. We can’t say that people are happy. At the same time, these pictures seem to say: we've been sent here and we can do it.”

Vello’s family pictures are very lovely. These photos also reflect a poor standard of living and very poor living conditions. But the general mood is still very positive. Those pictures raise many questions about their lives and faith. I was very touched by the pictures of two girls who are represented in many photos. It seemed to me that they were sisters. They were holding hands in every picture. You will not see it in the remaining 300 images. Even the couples aren’t holding hands. However, they never smile with their eyes in these pictures. Their facial expressions betray emotions such as anxiety and sadness. Were they the only close relatives to each other who were still alive…?”

Photography was a hobby for Vello. He wanted to capture the story of his family. But, at the same time, he also preserved the story of the entire nation. It was his ballad of Siberia and, at the same time, the story of all the Estonian deportees in Siberia. Vello's pictures help us get to the past. Securely and remotely. So that we never forget.

In 2026, the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory will open the Memorial Museum for the Victims of Communism in Patarei Prison. The Estonian state supports its establishment. The Estonian Institute of Memory calls on people to tell their (family) stories by donating materials (objects, photographs, diaries, documents, etc.) relating to the Soviet occupation, the Red Terror, persecution of people, and other resistance activities, to the museum.

If you want to donate materials for the future museum, please contact the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory via e-mail info@mnemosyne.ee or phone +372 664 5039.

List of sources.

Pilve, E., Poolamets M. (11.11.2021). Siberi küüditatute elust haruldased fotod teinud mees. – Ajaleht Maaleht.

See ei olnud sinu elu, sind suunati. (23.07.2021). – Ajaleht KesKus, 34-35.