25.12: The Collapse of the Soviet Union: A Timeline of Key Events

On December 25, 1991, Mikhail Gorbachev announced his resignation as President of the Soviet Union. One day later, the Union was formally dissolved. The Red Empire, the world’s first workers’ state, had broken apart into fifteen independent nation states. These events, and those of the months preceding them, were the definitive moments of the dawn of the new millennium.

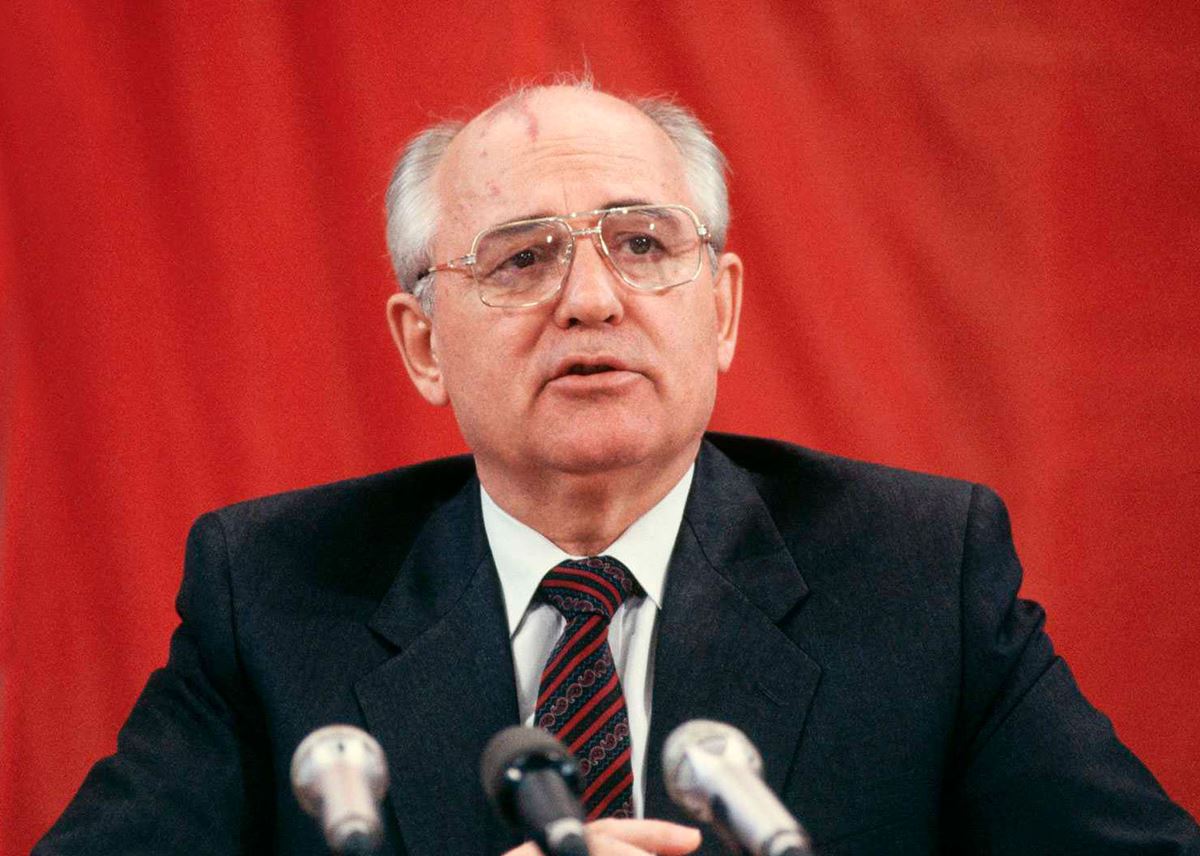

The road to this geopolitical climax was long. It is generally thought to have begun with the election of Mikhail Gorbachev to the post of General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), the de facto head of state. At 54 years old, he was the only Soviet leader to have been born after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. He had inherited the largest country in the world; over 22 million square kilometers and spanning eleven time zones, with a population of some 290 million people of various ethnicities. Gorbachev would oversee the destruction of this state, a process that would last only a few years and would culminate in a failed coup d’état against him, a last, desperate gasp of the pathetic old relics of the Stalin era to conserve the Soviet Union.

Learn more about the key events, figures, and themes of these historical turning points in communistcrimes.org’s timeline on the Soviet collapse:

March 11, 1985: Gorbachev is nominated General Secretary of the CPSU. A committed communist with firm convictions around the necessity of reform, his attempts to democratise the Soviet political system and modernise the economy would ultimately see the downfall of his state.

April 26, 1986: An environmental disaster ensues after a nuclear reactor at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in Ukraine explodes, dispersing a cloud of radiation across Europe. The explosion is caused by a faulty reactor design and inadequately trained personnel. Attempts by the Government to conceal the disaster directly contradict Gorbachev’s policy of glasnost (‘openness’ and ‘transparency’) on the world stage, and directly harm the Soviet populace through premature death and internal displacement. This coverup would continue, in part, for years to come.

1989: Gorbachev’s commitment to Soviet non-intervention in the affairs of foreign states accelerates the end of the Cold War. Two key events occur in 1989 to this effect. The first is the conclusion of the Soviet-Afghan War, a problem Gorbachev inherited from his predecessors which had raged for nine years at great human cost. The second is the wave of mostly peaceful revolutions against communist governments in Eastern Europe. Gorbachev reacts to the ‘loss’ of these satellite states, which had been seized by the Soviet Union as spoils of war in 1945, with seeming disinterest. By contrast, his predecessors had fought tooth and nail to preserve them by crushing anti-communist resistance in East Germany (1953), Hungary (1956), and Czechoslovakia (1968).

March 1989: Elections to the new parliament, the Congress of People’s Deputies, are held. The CPSU directly controls only one-third of the seats, making these the most democratic elections Russia has seen since 1917. This is an important step in breaking the CPSU’s monopoly on power. Rather than solidifying Gorbachev’s support base, voters are drawn to more radical democrats like Boris Yeltsin. The opposition also wins in many of the non-Russian republics.

August 23, 1989: The ‘Baltic Way’, a human chain between Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia, is formed to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939. The Pact had formed the basis for the illegal annexation of the three states by the Soviet Union in 1940. Though Gorbachev claimed “we can say the nationalities issue has been resolved for our country”, ethnic nationalism, partially enable by glasnost’s exposition of such controversial aspects of Soviet history, undermined the legitimacy of Soviet rule in these republics. While the leadership denounced nationalist ‘separatism’, many in the Baltic states viewed continued ‘membership’ of the Soviet Union as an ongoing occupation. Nationalism was also prevalent in other borderland regions of the empire.

- See online exhibition 'Chains of Freedom: the Legacy of the Baltic Way in Hong Kong', created in cooperation of the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory and human rights activists of Hong Kong, is to demonstrate solidarity with the Hongkongese people in their anti-communist aspirations for liberty. https://chainsoffreedom.communistcrimes.org/

January 1991: Soviet tanks and paratroopers undertake military operations in Lithuania and Latvia. In Lithuania alone, 14 civilians are killed, and hundreds more injured. Moscow’s intolerance for the ever-growing nationalism in the non-Russian constituent republics, especially in the Baltics, led to this display of force. These events, however, have the opposite effect to what was intended. Rather than intimidating the nationalist movements, the violence only strengthens their cause.

June 1991: Yeltsin was elected as the first President of the Russian Federation.

August 19, 1991: A coup d’état against Gorbachev takes place in Moscow. Acting in advance of the signing of the New Union Treaty, which was Gorbachev’s initiative to preserve the Soviet Union by granting more autonomy to the constituent republics, a so-called ‘State Committee on the State of Emergency’ (GKChP) is formed by representatives of the Soviet State, KGB, CPSU, and the military-industrialists. The putschists place Gorbachev under house arrest in his Crimean dacha and, after his refusal to cooperate, replace him with Gennady Yanayev as Acting President of the Soviet Union. The coup openly opposes democratisation and liberalisation, which are blamed for the socio-economic crises plaguing the country.

August 21, 1991: The coup is broken, and the Soviet Union has just days to live. Mass protests occur in Moscow when the coup is announced, and Yeltsin famously clambers atop a tank outside the Russian Parliament to give a speech denouncing the “right-wing, reactionary, anti-constitutional coup d’etat”. Three civilians are killed in clashes with the military. The coup is undermined by the weakness, indecision, and alcoholism of its instigators. Faced with mass unrest and an increasingly unsupportive military, the GKChP calls off its tanks.

December 25, 1991: Gorbachev gives his farewell speech, announcing his resignation as President of the Soviet Union. Despite his attempts to preserve some semblance of a union and his own place within it, he is forced to concede his position to Yeltsin, the inaugural President of the Russian Federation. The Union is replaced with a much weaker Commonwealth of Independent States, which does not include many of the former constituent republics. One day later, the upper chamber of the Supreme Soviet votes both itself and the Soviet Union out of existence, formally bringing the empire to an end.

List of sources.

Edele, Mark. The Soviet Union: A Short History. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2019.

Remnick, David. Lenin’s Tomb: The Last Days of the Soviet Empire. New York: Random House, 1993.

Seventeen Moments in Soviet History, Michigan State University. “Gorbachev Challenges the Party”. Accessed December 14, 2021. URL: http://soviethistory.msu.edu/1985-2/perestroika-and-glasnost/perestroika-and-glasnost-texts/gorbachev-challenges-the-party/

Taubman, William and Svetlana Savranskaya. “If a Wall Fell in Berlin and Moscow Hardly Noticed, Would it Still Make a Noise?”. In The Fall of the Berlin Wall: The Revolutionary Legacy of 1989, edited by Jeffrey A. Engel, 69–95. Oxford: Oxford University, 2009.

Taubman, William. Gorbachev: His Life and Times. London: Simon and Schuster, 2017.