Witch hunt after the Holocaust: anti-Jewish repressions in the Soviet Union

An in-depth story of how the Soviet Union, which had contributed to the destruction of Nazi Germany, made Anti-Semitism its policy after the Second World War. Many renowned Soviet citizens lost their lives, freedom or jobs during Stalin's anti-Jewish repressions. The most brutal of all was the destruction of the Jewish anti-fascist committee. Specialists in only one area didn’t have to be afraid because of their Jewish background. The author of the content is Artyom Kretchetnikov and it was first published on the BBC's Russian-language portal.

On 28 November 1948, Stalin signed a secret decision issued by the Bureau of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union: ‘The Jewish Antifascist Committee is to be disbanded immediately, the committee’s printing organs are to be shut down, the committee’s documents are to be confiscated.’

On the next day, operative agents from the Ministry of State Security searched the committee’s rooms and sealed its doors shut.

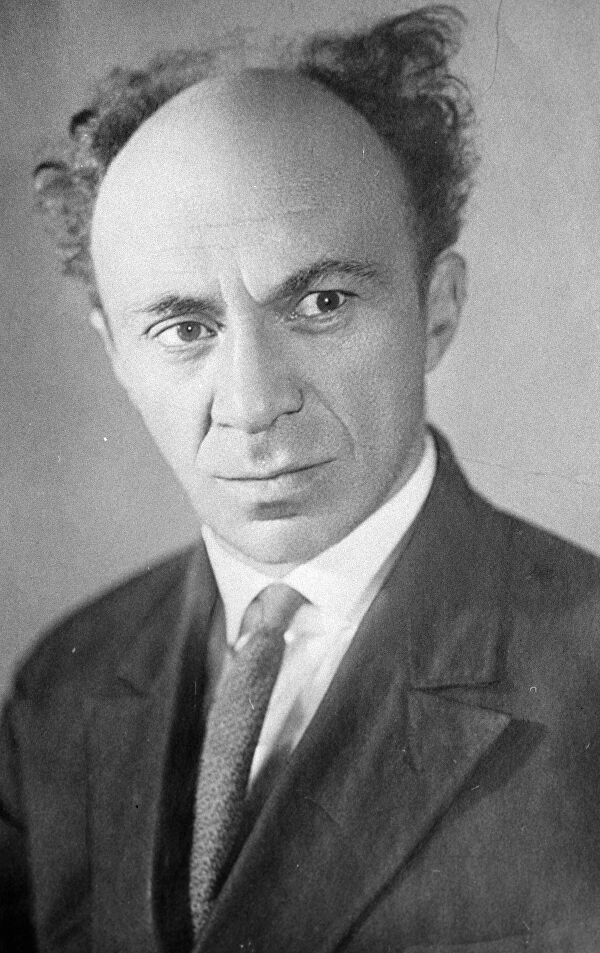

The chairman of the committee, the Artistic Director of the State Jewish Theatre Solomon Mikhoels, was already dead by that time. Seventeen of the committee’s 20 members were arrested, including the writers Perets Markish, Lev Kvitko, Semyon Galkin and David Gofštein, the first Soviet female academician Lina Štern, the former head of the Soviet Informburo Solomon Lozovsky, the chief physician of Botkin Hospital Boriss Shimelovitch, the actor Veniamin Zuskin, and the poet Itsik Fefer.

In total, 125 people were included in the affair, of whom 23 were shot and six died in prison.

The arrests were not disclosed. Everything looked as if well-known people had simply disappeared. When they were abroad, Aleksandr Fadeyev and Ilya Ehrenburg had to lie that they had just recently seen their colleagues in Moscow.

The Moor has Done his Duty

The Jewish Antifascist Committee was founded on 7 April 1942 with the aim of creating a positive image in the United States and Great Britain, and to collect donations. It originally consisted of 47 people, mainly creative intellectuals.

The committee fulfilled the aims that had been set for it. Contacts were established and 33 million dollars in donations were collected. In America, Albert Einstein headed the Jewish Council for Assisting Russia.

By 1948, relations between the Soviet Union and the Western countries had gone hopelessly askew, the need for the Jewish Antifascist Committee disappeared, and the services that its activists had previously rendered were now considered their faults.

The primary reason for falling out of favour is often considered to be a letter that had been sent to Stalin proposing the establishment of a Jewish autonomous oblast in the Crimea. Yet nearly five years separate that appeal (February of 1944) and the start of the repressions.

Interrogations Accompanied by Torture and Convictions without Evidence

An investigator with a mediocre education struck the writer Abram Kogan when Kogan started correcting mistakes in the transcript of his own interrogation: ahaa, so you know Russian, but you write your books in Yiddish?

Itsik Fefer testified in court that the investigator Likhachov had made it clear to him: ‘I’ll snap your neck, or my head will be chopped off. If we’ve already arrested you, we’ll surely find your crime as well.’

Stalin worked with young operatives at the Ministry of State Security like a professor works with postgraduates, infusing them with hope. He invited them to visit him at his summerhouse, personally revised documents, and told them how to draw up bills of indictment. He personally devised which questions investigators should pose. He personally decided who should be arrested and when, and which prison to keep them in. It can be said that Stalin performed the duties of the head of the Investigations Department for Especially Important Matters of the Ministry of State Security on a social basis.

Viktor Alidin, KGB veteran

Vladimir Komarov, another investigator who worked on the Jewish Antifascist Committee Case and who was later arrested for being close to the Minister of State Security Abakumov, who had in turn fallen out of favour, already wrote to Stalin from prison: ‘I especially hated the Jewish nationalists, in whom I saw the most dangerous and evil enemies, and was pitiless towards them.’

Regardless of torture, some intellectuals did not plead guilty to espionage and terrorism, for which reason the trial that began on 8 May 1952 was a trial in camera.

Something unprecedented happened in the course of the trial: the Chairman of the War Collegium of the Supreme Court, Lieutenant General Aleksandr Cheptsov, considered the charges unproven and turned to the Central Committee with a request to send the case back for investigation.

‘You want us to drop to our knees in front of those criminals. The people have approved the court verdict, the Politburo has deliberated it three times. Carry out the verdict!’ replied the Secretary of the Central Committee Georgi Malenkov.

Fourteen of the 15 accused defendants were shot. The only one who was sent to the Gulag was the world-famous physiologist and academician Štern, who had arrived from Switzerland to the Soviet Union in 1925 to build socialism. As it later turned out, Fefer had already been cooperating for years with the state security organs under cover of secrecy, but even that did not save him.

A Family Problem?

How can Stalin’s behaviour be explained?

Anti-Semitism that already stuck with him as a child (his private secretary Boriss Bazhanov, who fled to the West in 1928, insisted that his boss had already taken the liberty of making corresponding remarks back then in his narrower circle)?

Settling old accounts with Trotsky and other representatives of the ‘Leninist guard’?

The opinion that in the event of war with America the Jews would be an unreliable element?

Nowadays the viewpoint can be heard as if the harassment that befell the Jews in the Soviet Union was in revenge for their active participation in establishing Soviet power and destroying old Russia. Yet the post-war blow was not struck against the Communist Party-Chekist elite, with which accounts had already been settled in the 1930s, but rather against completely innocent Jewish intellectuals: scientists, physicians, writers.

The historian Leonid Mlechin affirms that the original reason for the Jewish Antifascist Committee Case was the deterioration in Stalin’s health, more precisely that which the Moscow correspondents from Western countries wrote about it. That irritated the elderly dictator a great deal.

The basis for speculations was Stalin’s physical appearance and his frequent disappearance from public view. That explanation nevertheless did not satisfy the leader. He was certain that somebody in his inner circle was leaking information on his medical problems to foreigners.

The Ministry of State Security found an explanation that satisfied their boss: information was leaking by way of the relatives of the leader’s deceased wife. At the end of 1947, Nadezhda Alliluyeva’s sister Anna was arrested, along with Yevgenia, the wife of her deceased brother Pavel, Yevgenia’s daughter Kira and second husband, the engineer Nikolai Molochnikov.

After having been beaten, Molochnikov ‘remembered’ under interrogation that his wife had a female acquaintance, who in turn had a daughter who married Vitali Zaitsev, who worked as an automobile driver at the American Embassy.

Zaitsev had allegedly ‘circled around Kira’ and asked for details on Stalin’s life. Upon his arrest, Zaitsev quickly ‘confessed’ that he was an American spy.

Well, he didn’t like them and that’s that! He also had political motives, but the basis was zoological anti-Semitism, for which no rational reasons are needed.

Aleksandr Nikonov, publicist

A necessary confession was also obtained from Yevgenia Alliluyeva. She made it known that her acquaintance Isaak Goldštein, a doctor at the Academy of Sciences Institute of Economics, was interested in details of Stalin’s private life.

‘I was brutally beaten at length with a rubber truncheon,’ Goldštein later testified. ‘Worn out by night-time and daytime interrogations, I started giving myself and others away.’

Goldštein testified against the head of the Jewish Antifascist Committee’s History Commission Zakhar Grinberg and the Committee’s chairman Solomon Mikhoels, who allegedly ‘exhibited heightened interest in the private life of the leader of the Soviet government, which interested American Jews’.

The Killing of Mikhoels

When Minister of State Security Viktor Abakumov and his first deputy Sergei Ogoltsov reported on all this to Stalin on 27 December 1947, Stalin said that the Jewish Antifascist Committee is a ‘centre of anti-Soviet propaganda and feeds anti-Soviet information to foreign intelligence agents’. According to Ogoltsov, it was right then that the oral order was issued to arrange an automobile accident for Mikhoels.

Grinberg died in prison. Mikhoels was killed in Minsk on the night of 13 January 1948. Mikhoels’s acquaintance, the theatre critic and Ministry of State Security agent Vladimir Golubov, was liquidated along with him because Golubov knew too much. Golubov had lured Mikhoels to an isolated summerhouse. The Chekists staged their death in an inebrious state beneath the wheels of a lorry.

Everyone who participated in that killing was decorated with medals in secret.

The journalist Leonid Mlechin made a documentary film in the 1990s in Minsk on the killing of Mikhoels. The leaders of the Byelorussian KGB asked him to give a presentation to their employees. Later Mlechin found out that the man who drove the lorry that ran over Mikhoels also sat among the veterans in the back rows.

How Did it All Begin?

Yet the Jewish Antifascist Committee Case was not an isolated episode. The first alarm bells already began ringing earlier. ‘State anti-Semitism emerged suddenly in the Soviet Union – and as strange as it may seem, it emerged precisely during the war waged against Hitler’s Germany. As if that infection had penetrated the front line and infected the higher-ranking leadership,’ wrote the historian Mikhail Voslensky.

It seems to me that Stalin believed in solidarity between people of shared origin. When settling accounts with his enemies, he took no pity on their relatives either. In any case, we have to assume that he attacked Jews because he considered them to be dangerous – all Jews are connected to one another by their origin, and several million Jews lived in America.

Ilya Ehrenburg, writer and journalis

Starting in 1943, an unwritten guideline was in effect prohibiting hiring Jews to work in the Communist Party apparat and in positions that required travel abroad.

In that same year, Svetlana Alliluyeva fell in love with the filmmaker Aleksei Kapler. Stalin sent the man to the Gulag – perhaps he spared his life only out of fear that otherwise his daughter might do something crazy like her mother did.

When Svetlana married Grigori Morozov, a student at the Moscow State International Relations Institute who was also a Jew, her father gave up but ordered his son-in-law to stay out of sight. Svetlana divorced Morozov three years later. Stalin’s henchman Georgi Malenkov considered this a signal and immediately forced his daughter to divorce her husband Vladimir Shamberg. Shamberg was not even given the chance to bid farewell to his wife – his belongings were removed from their home and he was given a passport where there was no longer any indication of his marriage.

The Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers in the field of machinery and mechanical engineering Vyacheslav Malyshev noted in his diary Stalin’s words from the session of the Presidium of the Central Committee on 1 December 1952: ‘All Jews are nationalists, agents of American intelligence.’

Yet nothing bad was said publicly about Jews until January of 1953, when the campaign known as the Doctors’ Plot was launched.

In the spring of 1949, Fyodor Golovenchenko, the deputy head of the Propaganda Department of the CP(B)SU Central Committee, said to the Communist Party activists who had been summoned to Podolski near Moscow: ‘So we say – cosmopolitanism. But what does that mean, how can we put it in simple language, the way a worker would say it? It means that all manner of Moishes and Abrahams want to take our places away from us!’ю This too outspoken apparat employee was expelled from the Central Committee and sent to head a chair of studies at the Moscow Pedagogical Institute.

A struggle was officially waged against ‘cosmopolitanism without a homeland’ and ‘grovelling in front of foreign countries’. In June of 1948, Yekaterina Furtseva, the First Secretary of Moscow’s Frunze Raion Committee and a future Minister of Culture of the Soviet Union, convened a meeting of directors of research institutions and secretaries of Party committees, and gave them a proper dressing down for the ‘poor organisation of the work in ideological-political education of research employees’. The word ‘Jew’ was not heard coming from her mouth, but the names of ‘politically immature’ researchers were Rubinštein, Osherovitch, Shifman, Gurvitch.

On 28 January, a direction-setting article appeared in Pravda entitled ‘On an Antipatriotic Group of Theatre Critics’, which contained only Jewish names and used the term ‘cosmopolitanism without a homeland’ for the first time. The newspaper’s editor-in-chief Pyotr Pospelov has recalled that Stalin personally dictated that expression to him.

Many scholars of literature, critics and translators were lumped in with cosmopolitans – and we were incapable of defending them. We realised how unjust the guidelines coming from higher up were, but we kept quiet, and thereby we became accessories to this disgraceful battue.

Aleksandr Puzikov, editor-in-chief of the periodical Hudožestvennaja Literatura

A three-day meeting of dramaturgs and theatre critics was opened in the Central Building for Writers on 18 February 1949.

‘This is counterrevolutionary activity, an organised group that has been cobbled together,’ thundered Aleksandr Fadeyev, the Chairman of the Writers’ Union, from the rostrum.

‘I was summoned by the Central Committee. What could I have done?’ he later felt pangs of conscience.

Anatoli Surov brought the anti-American play Green Street to the stage at Moscow’s Academic Art Theatre, and it was awarded the Stalin Prize in 1949. However, a scandal broke out a few months later: it turned out that ‘cosmopolitan’ ‘literary niggers’ who had been left without income had cobbled the text of the play together for him. ‘The hope of Soviet dramatic and performing arts’ was expelled from both the Party and the Writers’ Union – not so much for plagiarism as because he consorted with the wrong people.

After literature and theatre, the ‘struggle against cosmopolitanism’ spread to all spheres of life. Quite a few people eagerly hurried to participate in the battue – mainly with the aim of grabbing vacated positions for themselves.

The history professor Sergei Dmitriyev described in his diary how the purging of cosmopolitans from his faculty was discussed in March of 1949 at a session of the Academic Council of the Faculty of History at Moscow State University. ‘What’s behind all this in your opinion?’ Dmitriyev asked one of his colleagues. ‘War,’ his colleague replied with conviction. ‘The people have to get ready for another war. It’s coming ever closer.’

On 4 July 1950, Minister of State Security Abakumov (who was shortly arrested himself and was accused of collaborating with the ‘Jewish nationalists’) sent a memorandum to Malenkov informing him that 36 of the 43 research employees at the Moscow Therapeutic Nutrition Clinic were Jews and that the nationality of the patients was not indicated in the clinic’s case histories.

Pitiless killer dogs of dogmatism, yelping mongrels of demagogy, flabby-jawed bulldogs of the Black Hundred, trained bird dogs of hatred of Jews have been unleashed.

Juri Polyakov, historian, academician

In April of 1951, in response to a report from Abakumov, Lieutenant General Nikolai Oslikovsky, head of the school for higher-ranking cavalry officers, was dismissed from his post and sent to continue his service farther away from Moscow. The reason: there were Jews among Oslikovsky’s friends, but due to his position, he was responsible for training the horses of the men leading and receiving parades at Red Square – good heavens, what could that mean!

The chairman of the board of the Composers’ Union Tikhon Hrennikov found anonymous letters in his mailbox with texts such as ‘Tisha the blockhead saves Jews’.

The First Secretary of the Communist Party Committee of Birobidzhan oblast Aleksandr Bahmutsky was sent to prison camp for 25 years in February of 1952: he had encouraged the study of Jewish history, supported the publication of books in Yiddish, attended the funeral of Mikhoels in Moscow, and proposed that the Jewish autonomous oblast be turned into a republic.

At the age of 90, the academician Nikolai Gamaleya, a renowned microbiologist and physician who was a colleague of Pasteur and Metshnikov, no longer feared anybody or anything, and wrote to Stalin in 1949: ‘Something bad is afoot in the attitude towards Jews in our country in recent times. Anti-Semitism is being heard even from high-ranking persons…’

The Zhemchuzhina Case

Polina Zhemchuzhina, the wife of the influential Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Soviet Union Vyacheslav Molotov, also had to go through sufferings. Judging by all that is known about them, it seems that they loved each other. Stalin evidently did not start persecuting Zhemchuzhina in her own right, but rather because of her husband, whom Stalin wanted to get rid of, as numerous signs indicate.

The Jewish theme was once again raised in order to press charges against her.

On 27 December 1948, Abakumov and the Chairman of the Party’s Control Committee Matvei Shkiryatov sent Stalin the memorandum ‘On the politically undignified behaviour of Zhemchuzhina’: ‘Jewish nationalists have congregated around her, she has become their advisor and patron.’

‘Undignified behaviour’ was manifested primarily in contacts with Mikhoels and Fefer, visiting Moscow’s synagogue in March of 1945, and the fact that after the establishment of diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union and Israel, she attended the reception given by the Israeli Ambassador Golda Meir and conversed with Meir in Yiddish.

According to hearsay, Zhemchuzhina had allegedly uttered: ‘Now we have a homeland’, but that is hard to believe.

Zhemchuzhina was expelled from the Party at a Politburo session on 29 December. Molotov remained neutral in the vote, but thereafter confessed to Stalin in a letter of penitence that his behaviour had been politically misguided.

At the session and in the presence of Molotov, Stalin read out confessions that had been extracted through beatings from two former assistants of Zhemchuzhina stating that they had engaged in group sex with her.

She was arrested on 26 January 1949 and sent to Kustanai oblast. Her husband was unable to establish any sort of contact with her, only Beria is said to have occasionally whispered in his ear: ‘Polina is alive’.

Ten relatives and former co-workers of Zhemchuzhina were imprisoned along with her. Her sister and brother died in prison.

In 1955, the Chief Secretary of Israel’s Communist Party Shmu’el Mikunis met with Molotov at the Kremlin hospital and asked why he did not stand up for his wife. ‘Because I was obligated to submit to Party discipline,’ replied Molotov.

On 21 January 1953, Ministry of State Security investigators added the charge of ‘treason against the homeland’, the punishment for which was execution by shooting, to Zhemchuzhina’s list of sins. She had already previously been charged with anti-Soviet propaganda and agitation. At about the same time, Ryumin, the deputy head of the Ministry of State Security, said to his recent colleague State Security Lieutenant Colonel Issidor Maklyarsky while interrogating Maklyarsky after his arrest: ‘Zhemchuzhina is the leader of Moscow’s Jewish nationalists and an Israeli spy.’

Stalin’s death saved both her and Molotov.

The end came for the dictator on 5 March 1953. Molotov turned 63 four days later. Beria asked in the name of their colleagues what he would like to receive as a present. Molotov replied: ‘Give Polina back!’

Husband and wife lived together for another 17 years – remaining steadfast Stalinists.

Letter of Safe Conduct

The only group of Soviet Jews that was not subjected to persecution was the physicists.

We often came up with ideas for fundamentally new directions in technology, but they haven’t been developed further because they haven’t found recognition or favourable conditions.

Pyotr Kapitsa, physicist, academician

‘Scientists in the Party’ who had not found places for themselves in the atomic project launched a struggle against ‘bourgeois-idealistic’ relativity theory and quantum mechanics in 1947.

The Moscow State University Faculty of Physics became their nest. The Dean Vladimir Kessenikh became famous with the claim that Soviet scientists have no need to publish their works in English.

Pyotr Kapitsa (who incidentally was not a Jew), Abram Joffe, Vitali Ginzburg, Lev Landau, Aleksandr Frumkin, Yakov Frenkel, Yevgeni Lifshits and many others were accused of ‘slavish grovelling before Western science’.

On 4 December 1948, the Secretariat of the Central Committee ordered the preparation of a USSR-wide congress of physicists. Aleksandr Topchiyev, the Deputy Minister of Higher Education and the chairman of the congress organising committee, explained the task: ‘Our congress has to be at the same level as the VASHNIL session [the session of the USSR-wide Academy of Agricultural Sciences held from 31 July to 7 August 1948, at which genetics was condemned as a ‘reactionary false science’].’

Yet this congress was initially postponed from the end of January to March, but then was shelved altogether. In March of 1949, the Minister of Higher Education Sergei Kaftanov sent the Central Committee a list of Jewish professors who were teaching physics at universities, but none of them were touched.

It turns out that the scientific director of the atomic project Igor Kurchatov is said to have curtly explained to his superior Lavrenti Beria: ‘If the theory of relativity and quantum mechanics are prohibited, then there will be no bomb either.’ Beria reported this to Stalin. The argument was understood.