Justice and condemnation

Since the 1990s, persons guilty of crimes of communist regimes have been taken to court in many former Eastern Bloc countries. For many years, appeals have been issued for the formation of an international tribunal to try the crimes of communism.

The international military tribunal formed in Nuremberg in 1945 is seen as the model for such a tribunal. Demands are being made for treating of the perpetrators of the crimes of all totalitarian regimes, both nazi and communist, on an equal basis. This has not happened and there are several reasons for this.

First of all, militarily defeated Germany capitulated unconditionally in 1945, which allowed the victors to put the losers on trial under conditions dictated by the victors. The Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc ceased to exist in 1989–1991 as the result of domestic and foreign political processes and agreements.

Although the dictatorship of the Communist Party was replaced by parliamentary democracy in most of these countries, a clear dividing line was not drawn between the old and the new. A large number of the members of the former communist elite carried on as members of democratic parliaments and governments, and in many countries, they were democratically elected to the highest posts in the state administration.

Secondly, unlike the leaders of National Socialist Germany in 1945, the initiators and leading executors of the most brutal and massive crimes of the communist regimes were dead by the time that the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc collapsed. Minor followers of orders have been convicted in many countries.

Thirdly, there is a great deal of support in the world for the position that the idea of communism was nobler than the idea of Nazism and that it was primarily Stalin and his retinue in the Soviet Union and its satellites in Eastern Europe who misused the idea and were guilty of the millions of victims of communist regimes, but not the communist ideology itself. This is also expressed in the name of 23 August in many countries: the day of remembrance for victims not of Nazism and communism, but rather of Nazism and Stalinism.

Fourthly, left-wing totalitarian ideologies have enjoyed a great deal of support after World War II due to the Soviet Union’s role and enormous blood sacrifice in destroying Hitler’s Germany and Japan, and in liberating captured countries and peoples.

Legally speaking, there is no such thing as nazi or communist crimes. Different penal codes and criminal codes are in effect in different countries. The international tribunals of Nuremberg and the Far East found the accused guilty of either war crimes, crimes against humanity, or crimes against peace (aggression).

The UN General Assembly adopted its convention on genocide in 1948. These necessary elements of the crime of genocide have served as the basis for the conviction of persons accused of the crimes of the nazi and communist regimes in the courts of individual countries. Persons accused of the crimes of the nazi and communist regimes have also been convicted according to the necessary elements of the crime of murder and of other crimes.

People have been convicted and punished for the crimes of communist regimes since World War II, but these have not been verdicts of courts of countries based on the rule of law. In 1941–1944, nazi state security agencies in the occupied western part of the Soviet Union and in countries and territories occupied by the Soviet Union sentenced thousands of people to death, many of whom were accused of participating in communist mass repressions.

After Stalin’s death and the dismissal of Lavrenti Beria from his post, Beria and many officers of the state security organs were convicted and executed in the Soviet Union in 1953. This was the result of a power struggle within the Communist Party and not of an equitable trial of a man guilty of mass terror. In 1956, Nikita Khrushchev, the leader of the Soviet Union, gave a secret speech at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union on Stalin’s personality cult and its consequences, in which he focused primarily on the repressions of communists in 1937–1938 and blamed Stalin and the leadership of the NKVD.

While the change in power took place without bloodshed in most countries of the former Eastern Bloc in 1989, President Nicolae Ceaușescu’s recent retinue imprisoned the former president and his wife Elena during the violent change in power in Romania in December. A court martial sentenced both to death and they were executed on the same day. The procedure resembled the way Beria and his retinue were sentenced to death 36 years earlier.

The German Democratic Republic was joined together with the German Federal Republic in 1990. Court cases were launched against Erich Honecker, the leader of the Communist Party of the GDR, Erich Mielke, its Minister of State Security, and Markus Wolf, its head of foreign intelligence. All three had served in their positions for several decades.

Honecker was charged with violating human rights during the communist regime, but the trial was suspended due to the poor health of the defendant. Mielke was instead convicted of a murder committed in 1931 as a member of a communist storm troop and served a four-year sentence in prison. Wolf was arrested in 1991 and charged with treason. Germany’s Constitutional Court decided in 1993 that the German Democratic Republic was a sovereign state and that foreign intelligence was in compliance with its laws. The charge was nullified.

Special investigation institutions for dealing with the period of the communist regime were formed in most countries of the former Eastern Bloc. In many countries, the archives of the former secret police, investigation, so-called lustration, or background checks on individuals applying for public positions of power, and historical research have been combined into a single institution.

These institutions are subordinated to parliamentary control and members of different parliamentary parties belong to their boards. The largest of these institutions is the Polish Institute of National Remembrance. Estonia and a few other countries are exceptions. In Estonia, the National Archives are responsible for all archives, while the investigation of international crimes not subject to statutes of limitations and questions connected to oaths of conscience are under the jurisdiction of the Estonian Internal Security Service. The Estonian Institute of Historical Memory deals with historical research and publicity work.

Since the 1990s, persons guilty of crimes of communist regimes have been taken to court in many former Eastern Bloc countries. Different crimes are investigated in different countries. While deportations and the struggle of the Soviet state security organs against the resistance movement (the forest brothers movement) have been focused on in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, border shootings – the killing of people at the border who tried to escape to the Western countries – have been at the centre of the attention of the law enforcement agencies of the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Germany.

A number of offenders have been tried in court and received punishment. The accused at trial have been charged with genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. Elderly accused at trial have mostly been convicted conditionally, but some have also been sentenced to actual prison terms. Some court cases have been appealed at the European Court of Human Rights, which has upheld the verdicts of the courts in the countries where the corresponding trials had been held.

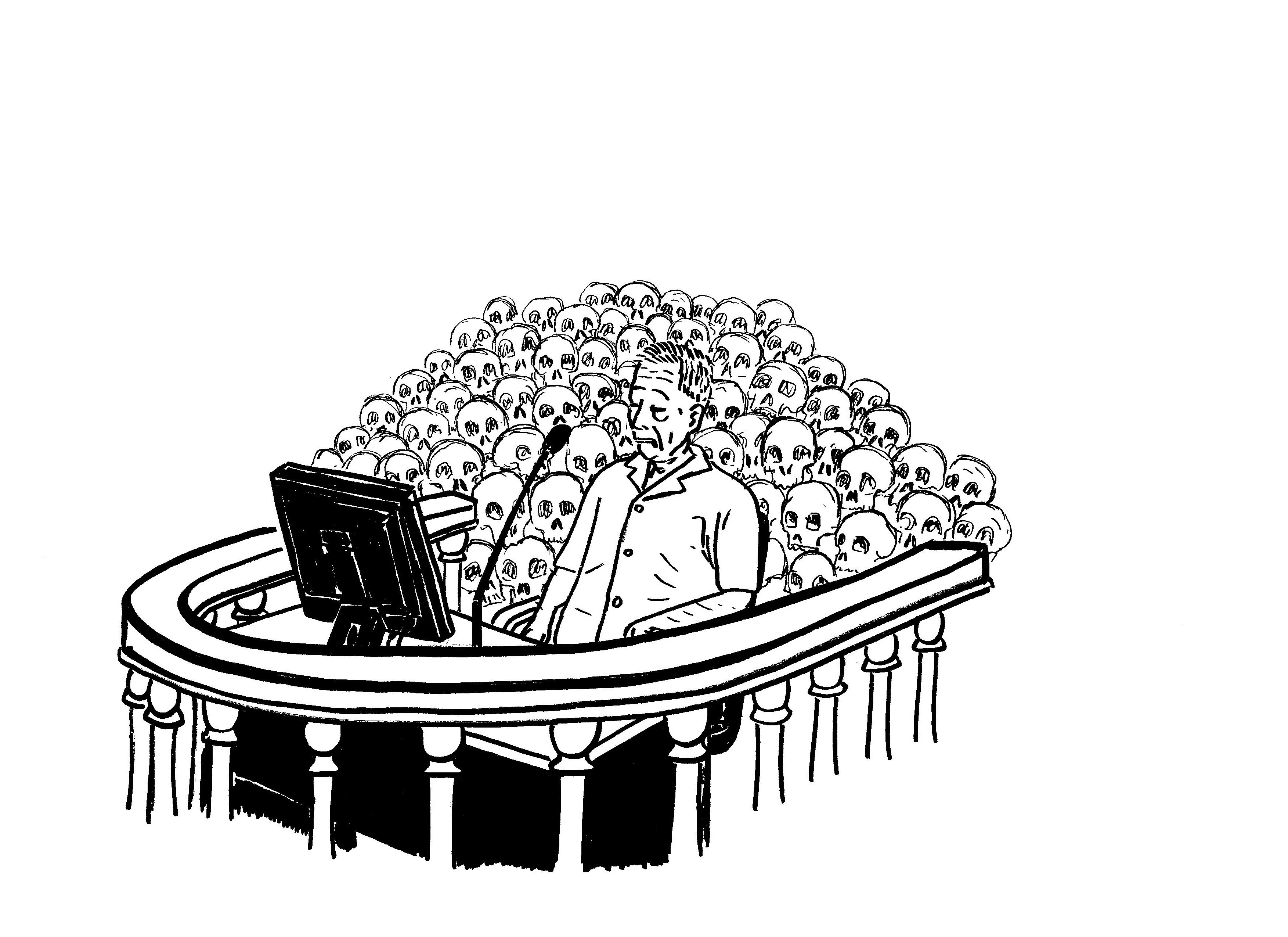

Attempts to establish an international court, or at least a transnational investigation institution, for investigating the crimes of communist regimes continue to be made to this day at the initiative of numerous countries, but without any particular success. Political parties supported by voters who feel nostalgic towards the ‘socialist era’ are very influential in a number of countries of the former Eastern Bloc. Western European countries demonstrate little interest in this question.

On the one hand, it is not really an issue for them, yet on the other hand, left-wing parties relate to such proposals as indirect ideological attacks or also as an attempt on the part of Eastern European countries to use this to hide the collaboration with Hitler’s Germany of their politicians and compatriots of the past, including in carrying out the Holocaust.

Russian propaganda has also played a role in this by using the prosecution of people charged with crimes of communist regimes to accuse those countries of cooperation with the Nazis in the past and of attempting to rehabilitate men and women who had participated in nazi crimes. Propaganda in this direction was particularly active around the turn of the century, when it was one of the propaganda weapons used in the attempt to prevent Eastern European countries from joining the European Union and NATO.

The collapse of communist regimes and the crimes committed during the period when those regimes exercised their power are receding ever further into the past. Over time the number of people who fell victim to those crimes, as well as their family members and relatives, is decreasing, and along with this the importance of this topic is also declining in the general public consciousness. This, however, does not mean that international crimes, crimes against humanity, war crimes and genocide, all of which are not subject to statutes of limitations, can be forgotten and in this way forgiven.