Stalinism: A Period of Heightened Deportations and Inconceivable Cruelty

Meelis Saueauk and Tõnu Tannberg give an overview of Stalinist deportations from 1930 to 1952. The authors argue that although the Bolsheviks carried out the first deportations during the Russian Civil War, this form of repression is primarily connected to the period of Stalin’s regime.

The article is fully published in the proceedings of the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory 2 (2019): “Priboi” Files: Articles and Documents of the March Deportation of 1949. Ed. Meelis Saueauk and Meelis Maripuu. The book includes seven academic articles that examine various aspects of the March deportation, or Operation Priboi, which was the USSR’s most extensive deportation operation of the post-war years, affecting all three Baltic states. The aim of the operation was to eliminate resistance to collectivisation in rural areas. The book also contains a complete Estonian translation of the Estonian SSR’s Ministry of National Security’s “Priboi” file, as well as other documents related to the operation. The book can be purchased online from the University of Tartu Press, Apollo and Rahva raamat.

Although the first deportations were carried out by the Bolsheviks during the Russian Civil War, this form of repression is first and foremost connected to the period of Stalin’s dictatorship. Therefore, the title “Deportations During the Stalinist Era” or “Stalinist Deportations” is well justified. A total of six million people were estimated to have been deported during the period from 1930 to 1952.[1]

Mass deportations stopped after Stalin’s death in 1953. For simplification purposes, massive deportations in the Soviet Union during the Stalinist era can be classified into the following broad categories:

- Ethnic cleansing of frontier areas and main cities, as well as the deportation of criminal contingents (in several waves, 1928 – 1938);

- Mass deportation of “kulaks” in 1930 and subsequent years;

- So-called mass operations in territories annexed in 1939 – 1940 (including the June deportations);

- Deportation of representatives of nations at war with the Soviet Union (Germans, Finns, etc.) during the war from 1941 to 1945;

- Deportations of entire nationalities in the USSR, as well as whole groups (e.g., Vlasovtsy), accused of collaboration with the Germans and of opposing Soviet power, from 1943 to 1946;

- Post-war deportations.

The deportation of the more prosperous farmers or “kulaks” in the 1930s was the largest operation carried out between the two world wars. This was part of the policy and campaign of “eliminating the kulaks as a class”, aimed at removing the obstacles to the collectivization of agriculture and establishing kolkhozes. The campaign was launched by resolution of the holder of ultimate power in the country, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), “on measures to be taken for the liquidation of kulak ownership in complete collectivization regions”, adopted on 30 January 1930.[2] The measures included the prohibition of renting land and hiring labour, confiscation of means of production and property of the “kulaks”, and repressions, which included deportation.

Based on the Politburo’s resolution, the Operational Directive of the Unified State Political Administration or OGPU (Russian: Объединенное государственное политическое управление, ОГПУ) No. 44/21 of 2 February 1930, “about the liquidation of the kulaks as a class” introduced the repressive measures, including imprisonment and deportation.[3]

It is this wave of deportations that first laid down the principles that were to be used in later operations (including the 1949 March deportations) as well:

- The deportations were mass operations, carried out by state security forces under orders from the highest political body, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks). The latter decided upon the categories of deportees, the destinations, as well as the numbers or quotas and other relevant circumstances. Based on these instructions, the security services developed a detailed plan of the operations, made the required preparations, and conducted the operations;

- Depending on the nature of the repressive measures, the objects of the mass operations (i.e., the deportees or so-called special contingent) could be divided into categories. In this particular case the objects – kulak households – fell into three categories, depending on the level of their alleged hostility: 1) persons to be arrested and sentenced to death or sent to concentration camps, 2) families to be deported (i.e., “to be expelled to the remotest areas of the Soviet Union”), 3) families to be resettled within their home district. Persons assigned to category 1 had to be arrested first, so that their families could be deported along with category 2 families;

- Temporary local extrajudicial bodies of the state security services (operational troikas) were established for managing the operations. The troikas had the right to issue sentences and decide on their severity. The sentencing was carried out hurriedly and on a mass scale. There were collection or loading points in railway stations, supervised by commandants;

- To supress any resistance, troops were brought in. Only internal troops were used, and the regular army could only be deployed in exceptional cases;

- The items and the amounts that the deportees were allowed to take along were regulated;

- The families of persons serving in the Red Army were not subject to deportation;

- The deportees remained under supervision in their places of exile.

The operations launched during the winter and spring of 1930 continued the following year as well. More than two million people had been deported by October 1931.[4] The kulaks imprisoned during this operation laid the foundation for the populations of the newly established GULAGs.

The deportations occurred mainly in the fertile grain-growing regions, in an effort to encourage the establishment of kolkhozes on a mass scale.

The deportations occurred mainly in the fertile grain-growing regions, in an effort to encourage the establishment of kolkhozes on a mass scale. But the most characteristic result of the kulak operation was famine on an unprecedented scale.

In principle, the same procedure was followed during the mass operations in East Poland in 1940 and the recently annexed Baltic States in June 1941 (the June deportations). However, it is not really appropriate to call the operation a “deportation”, for one third of the people taken by Soviet authorities were arrested and incarcerated in prison camps.

The remaining two-thirds were deported. In absolute terms, the deportations in the Baltic States were smaller in scale and in comparison, to Western Ukraine; in total slightly over 40,000 people were taken from their homes. As a result, security forces were able to carry out operations in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania at the same time. This is known to be one of the last mass deportations where troikas were used.

When the war broke out between Germany and the Soviet Union, the focus of deportations turned to the Germans and other nations belonging to the Axis powers and their allies living in the USSR. The same practice was followed in liberated or newly conquered territories.

Therefore, in 1945 all Germans still residing in Estonia were deported. The most barbaric episodes of war time deportations occurred in 1943 – 1944 in the Soviet territories that were liberated first — entire nationalities were exiled as revenge for their collaboration with the Germans and anti-Soviet attitudes. Six nationalities suffered this fate: the Karachays, Kalmyks, Chechens, Ingush, Balkars, and Crimean Tatars. The nations with the largest number of deportees included the Chechens and Ingush (Vainakhs), who were deported en masse in February 1944 — more than 478,000 persons were exiled. There are witness statements to the effect that the inhabitants in some auls (villages) were killed by Soviet authorities who set their houses on fire.[5]

Post-War Deportations

The Second World War ended in 1945. On 8 August 1945, the representatives of the Allied Forces signed the Charter of the International Military Tribunal in London. According to the charter, deportations were defined either as war crimes or crimes against humanity, depending on the circumstances. Deportations were consigned to the past, or so it was thought.

In the internal territories of the Soviet Union, the end of the war brought a few years of relative quiet — there were no mass deportations, apart from some smaller operations. During those years, the main emphasis was on expelling the Germans from recently occupied East Prussia and the Japanese and Ainu from southern Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands. In addition, a population exchange was carried out along the western border areas of the USSR — Polish people were sent to Poland and Ukrainians, Russians, etc. were brought back to the Soviet Union.

In the territories under Soviet control, it was the western areas that were the “most problematic”.

These operations were generally conducted by the NKVD, (i.e., the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) headed by Lavrenty Beria. Another activity pursued in those years was the repatriation policy. Its aim was to persuade people who had left the country during the war to return to the Soviet Union or even force them to come back, based on the Yalta Agreements. Among those facing pressure to return, were people from the Baltic nations who had been made Soviet citizens against their will.

In the territories under Soviet control, it was the western areas that were the “most problematic”. These regions were first seized in 1939 – 1940. They then suffered under the German occupation and were re-annexed in 1944 – 1945. These people were not ready to give up their freedom and tried to hide from repressions that had taken the form of violence and terror. Naturally, the anti-Soviet opposition was most widespread in Western Ukraine, followed by Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia.

The largest wave of mass arrests occurred in these areas after they were re-annexed by the Soviet Union in 1944 – 1945.

Armed struggle in Ukraine was led by the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists or OUN (Ukrainian: Організація Українських Націоналістів). While deportations became a permanent feature of the Soviet political landscape in the Ukraine, they became extensive and increasingly prominent in 1947.

The largest deportations in this region took place in the autumn of 1947, when the Ministry of State Security or MGB (Russian: Министерство государственной безопасности СССР) was reorganized. This development led all efforts to be directed towards the liquidation of the anti-Soviet resistance movement.

On 24 May 1947, the Deputy Minister of State Security of the USSR, Lieutenant General Sergey Ogoltsov, and the Minister of State Security of the Ukrainian SSR, Lieutenant General Sergey Savchenko, sent a letter to the Minister of State Security of the USSR, Viktor Abakumov. The letter included a proposition to expel the families of members of the OUN and of other bandits from Ukraine. Ogoltsov and Savchenko wrote:

“Expulsion of families of the OUN members and bandits proved to be a rather effective method of combating the OUN resistance. It has considerably helped break up the underground groups and gangs, encouraged them to turn up and confess their guilt, made it more difficult for the OUN chiefs to recruit new members and bandits, motivated those who confessed to actively fight against the gangs, reduced the support base of OUN, for the local population refused to provide material assistance to the bandits, in fear of such repressions.”[6]

Operation “Zapad”

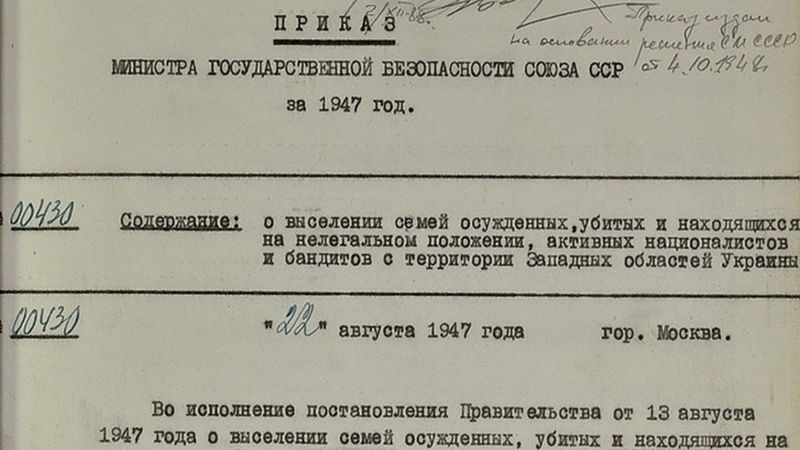

In response to the above letter, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) adopted the decision to launch the process of expulsion on 13 August 1947. The operation, codenamed “Zapad”, was initiated by the Minister of State Security Abakumov as Order No. 00430 of 22 August 1947. It focused “on [the] expulsion of families of convicted, killed and active underground nationalists and bandits from the territory of the western regions of Ukraine”.[7]

The categories of individuals that were to be expelled were listed in the title of the order — families whose relatives had participated in the resistance movement and had since been convicted for this offence, killed on the spot, or had gone into hiding.

The authors of the proposal, Generals Ogoltsov and Savchenko, were put in charge of the expulsion. To secure the success of the operation, the Deputy Minister of State Security of the USSR, Lieutenant General Afanasii Blinov, was tasked with securing the necessary transport and fuel. The Head of the USSR MGB Chief Directorate for Internal Troops, Lieutenant General Pyotr Burmak, was responsible for engaging the MGB internal forces. Furthermore, Lieutenant General Aleksandr Vadis was dispatched to the Ukraine. Abakumov immediately notified the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Ukrainian Communist Party (Bolsheviks), Lazar Kaganovich, and the Chairman of the Council of Ministers, Nikita Khrushchev, in an effort to ask them to provide all necessary assistance.

Special operatives from the USSR MGB were appointed to carry out the operation in the oblasts. They were assigned deputies who were in charge of operational matters and troops. The special operatives were security officers seconded on a temporary basis, so that they could keep their regular posts. They had to have the rank of a general or polkovnik and had to come from outside the Ukraine. This form of pair-based management, in which a special operative from Moscow and a local security chief were combined, was also practised during later mass deportations.

The special operatives had to start working without delay, as the operation was scheduled from the 10th to the 20th of October. The preparations had to be completed in less than two months and in complete secrecy, so that the deportation would come as a surprise to the various populations and serve its purpose.

The use of code names is characteristic of the way the MGB operated — as a rule, operations and operative files were assigned code names. The code name “Zapad“ (the Russian word for “west”) in the case of the Ukraine is a clear reference to the region involved. By and large, the same code name was not used for similar future operations.

The instructions for conducting the operation, appended to the above order and signed by General Ogoltsov are of great interest as well.[8] The deportations were to be carried out at the operational level of the raion (district). Like the rest of the Soviet territory, the Ukrainian SSR was divided into oblasts and then into raions. The special operative appointed for every raion had to prepare a plan for the operation. Together with the MGB raion chief, they had to determine which families would be expelled and prepare case files about them. Local authorities had to organise the receipt and further use of the cattle and other property of the evicted families.

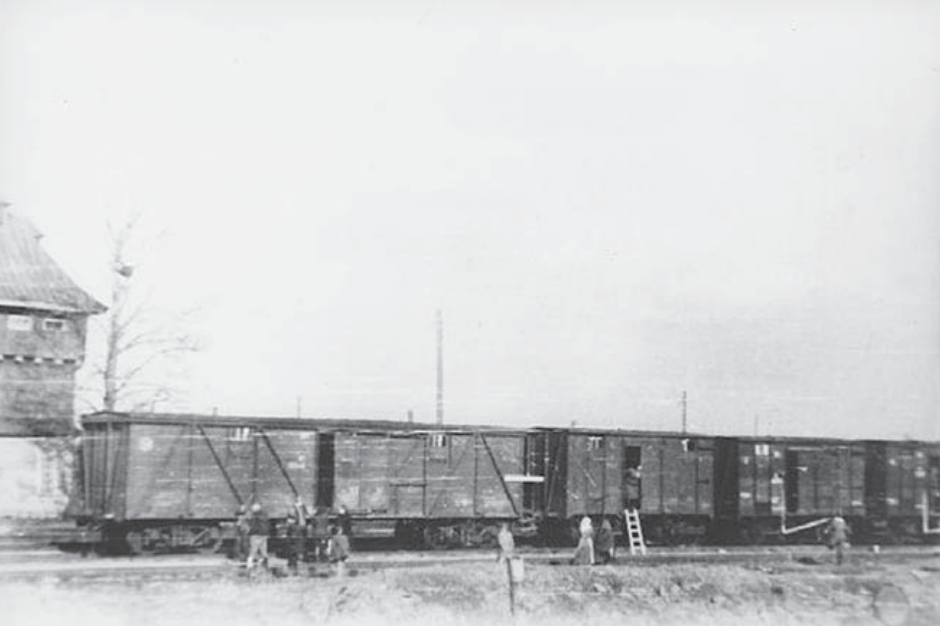

In addition, local Soviet sympathisers were involved in the deportation process. This was a general practice in all deportations. The deportees had to be told that they were being expelled because of the active anti-Soviet activities of their family members. The instructions defined the procedure for the operative conducting the deportation of a specific family. The families were to be taken from their homes to either collection points or directly to loading points (i.e., railway stations where people were loaded onto trains). There, the operatives handed over the families and their documents to the train commandant.

Operational groups brought together the deportation units of one settlement. A deportation unit was made up of the lead special operative, a few soldiers from the internal forces, and some local activists. One unit was to take care of 3 – 4 families. Later, the instructions were amended and the actual procedures were likely to have been slightly different from what was originally prescribed. Similar instructions for carrying out deportations had been drafted before and were also revised later, as authorities added to them as their experience grew. This is why the documents for the operations “Zapad“ and “Priboi“ are relatively similar.

Next, the planning and preparatory phases of the operation began. On 29 August, just a week after the order was issued, a meeting was organised in Lviv, which was the centre of the operation. In Lviv,

the USSR MGB special operatives and the Ukrainian SSR MGB oblast chiefs carefully studied the order and instructions issued by the USSR Minister of State Security. A few days later, similar meetings were held in oblast centres for the chiefs of the local MGB departments. A total of 44,192 case files had been sent to Lviv from the raions and 31,364 of them, concerning 99,675 persons, had already been finalised (i.e., were signed by the Minister of State Security and the Prosecutor of Ukraine). Based on these numbers, the plan for the necessary rail transport was created for more than 100,000 persons from 90 loading points.

The operational plans were developed at the oblast level and were signed by the USSR MGB special operative. The plans defined the following:

- The number of families and persons belonging to the special contingent to be expelled (the deportees);

- The personnel required (MGB operatives, soldiers from the internal forces, and auxiliary staff);

- Course of action: the operational groups (i.e., new name for deportation units) were to enter the homes of the deportees at the same time at 6:00 in the morning (dawn);

- The means of transport required;

- The loading points required and the procedure to be followed at loading points;

- Operational management. Operational command was set up in the oblast, constituting the USSR MGB special operative, the MGB oblast chief, deputy special operative in charge of troops, and assistants of the special operative responsible for communications and transport. The raions also had their own command of five members and a special operative in charge. Several raions together made up so-called operational sectors, headed by the commandant of the loading point;

- Measures to suppress any resistance.

During implementation, the original instructions had to be amended, for it seemed that the authorities did not have much experience in conducting deportation operations on such a large scale. This led the technical side of the operation to developed as they went along.

The MGB did not carry out the operation alone, for the Ministry of Internal Affairs or MVD (Russian: Министерство внутренних дел) was involved as well. Their function was to support and safeguard the operation. The MVD provided personnel, received and loaded the deportees on trains, transported them to their destination, and placed them under special watch upon arrival.

In 1941 the Ministry of Internal Affairs (i.e., Beria’s NKVD) had acted as the “Big Brother” of state security, but by now the situation had reversed: the MGB had taken over important areas from the MVD, minister Abakumov was behaving in a patronising manner with respect to the MVD top management, and a rivalry developed between the two ministries. The Ministry of State Security was expressly given the lead in organising the deportations.

Secrecy was not always maintained when preparing for “Zapad”. For example, the questionnaires about families were filled in by involving the heads of these same families. In addition, official certificates concerning the composition of families were obtained from village soviets, etc. Obviously, such behaviour was condemned but as a result of its occurrence, a number of families were able to go into hiding. Persons responsible for the preparations learned that the plans for the deportation had become widely known among the population. This is how a person from Rovno described the situation in a letter: “At present we are leading a temporary life, because families were put on the list, yours too, and also our Yevgeny and Katya, as well as many others. So, the people just walk around as if drunk and cannot move their hands.”

To conceal their plans, secretaries of the Communist Party’s Raion Committees were only given 2 – 3 days advance notice of the upcoming operation. Deportations started on 21 October, at 6:00 in the morning, and a few hours earlier in Lviv. The operation did not proceed without incidents and the number of people rounded up was considerably smaller than planned. Based on the MVD data, a total of 77,791 persons from 26,332 families were deported during operation “Zapad”.[9]

One should be cautious of these precise statistics when it comes to such large numbers. The data most likely reflects a specific moment, e.g., when the people were loaded onto the trains. A number of people were deported later, followed their families, died along the way, were born in exile, etc. It can also be argued that the individuals who were on the lists for deportation but eventually avoided being sent away were also victims, for they could be stripped of their possessions and become exiles in their own homeland.

The year 1947 also saw the launching of the campaign of creating collective farms (kolkhozes) in the Baltic States. By that time, this problem had been solved in the Ukraine. The fight against the Baltic kulaks (i.e., economically independent, more prosperous farms) had actually already started in 1946. These efforts amounted to an attack against farms and the whole village life of the region. On 21 May 1947, the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) adopted a decision to establish kolkhozes in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Therefore, the issue of eliminating the “kulak elements” who were blamed for hindering collectivization, became ever more topical in the region. The mass deportations practiced in the Soviet Union in the 1930s was the method chosen to address this issue.

Lithuania was hit first, for the country’s population was as large as that of Estonia and Latvia’s put together. Furthermore, it had the strongest resistance. Like the Ukraine, Lithuania had suffered from other deportations from 1945 to 1947, with a few thousand people taken at a time. According to MVD data, more than 10,000 persons were deported from Lithuania during that period.[10]

The largest mass deportation was organized in Lithuania barely a year after the one that took place in the Ukraine, in 1948. It was ordered by the USSR Council of Ministers’ 21 February 1948 Decree No. 417-160ss19 “on the deportation from the Lithuanian SSR of the family members of illegally residing bandits and nationalists, and accomplices of bandits, and kulaks”. A total of 48,000 persons from 12,134 families were to be exiled to Krasnoyarsk Krai, Irkutsk Oblast and the Buryat-Mongol ASSR.[11]

Operation “Vesna”

In addition to the families of resistance fighters, kulak families were also included in the categories to be deported. The operation was carried out from the 22nd to the 27th of May under the code name “Vesna” (Russian: “spring”) — an obvious reference to the season in which the deportations occurred.[12] According to different sources, 11,233 families (including 8,228 kulak families), with 39,482 persons altogether were deported to the designated regions. However, the targets set for the operation were not met.[13]

On 26 November 1948, the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet adopted a decree under which the persons exiled to remote regions of the Soviet Union during the period of the Great Patriotic War, in particular whole ethnic groups who had been deported as punishment, had to remain in permanent exile (i.e., until their death). Those who escaped from deportation sites were convicted and had to serve 20 years in hard labour camps. This was a severe penalty, even then. As the Soviet Union had suspended the death penalty at the time, the maximum possible penalty was 25 years of hard labour. Criminal charges were also brought against those who sheltered the individuals who had escaped from their places of forced settlement.[14] It soon became clear that the decree was applied not only to those who had been exiled during the war, but also to people deported after the war, including the 1949 March deportations.

The article is fully published in the proceedings of the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory 2 (2019): “Priboi” Files: Articles and Documents of the March Deportation of 1949. Ed. Meelis Saueauk and Meelis Maripuu. The book includes seven academic articles that examine various aspects of the March deportation, or Operation Priboi, which was the USSR’s most extensive deportation operation of the post-war years, affecting all three Baltic states. The aim of the operation was to eliminate resistance to collectivisation in rural areas. The book also contains a complete Estonian translation of the Estonian SSR’s Ministry of National Security’s “Priboi” file, as well as other documents related to the operation. The book can be purchased online from the University of Tartu Press, Apollo and Rahva raamat.

Meelis Saueauk is a Senior Researcher at the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory. In 2013, he received the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History at the University of Tartu. Saueauk is the author of the monograph "Propaganda and Terror" and the author and co-author of a number of articles on 20th century Estonian history. His main research interests include the period of Stalinism in the Baltics, the history of state intelligence and security services, and the units of Estonian soldiers who served in the Finnish Army during the Second World War.

Tõnu Tannberg is Professor of Estonian History and the Research Director of the National Archives at the University of Tartu. He is a co-founder and member of the supervisory board of the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory and a member of the editorial boards of several scientific publications. Tannberg's main areas of research include the political history of the Estonian SSR, the military history of Baltics from 1710 to 1917, and 19th and 20th century Russian history.

Literature

[1] Oleg Hlevnjuk, Stalin: diktaatori uus elulugu (Tallinn: Tänapäev, 2016), 49.

[2] Трагедия советской деревни. Коллективизация и раскулачивание. 1927–1939. Документы и материалы. В 5-ти тт. / Т. 2. Ноябрь 1929 – декабрь 1930, под ред. В. Данилова, Р. Маннинг, Л. Виолы (Москва: РОССПЭН, 2000), 126–130.

[3] Ibid., 163–167.

[4] История сталинского Гулага, 65.

[5] Сталинские депортации, 438–439.

[6] Олег Бажан, „Операция „Запад“: Из истории депортации населения Западной Украины в Казахстан,“ – 65 лет с начала депортации жителей Украины в Казахстан. Сборник материалов заседания круглого стола 20 ноября 2012 года (Караганда, 2012).

[7] Приказ Министра государственной безопасности Союза ССР за 1947 год № 00430 о выселении семей осужденных, убитых и находящихся на нелегальном положении, активных националистов и бандитов с территории Западных областей Украйны, 22.08.1947, Електронний Архів Українського Визвольного Руху, http://avr.org.ua/index.php/ viewDoc/25252/ (17.02.2020).

[8] Инструкция о порядке проведения выселения семей активных националистов и бандитов из Западных областей Украины, 22.08.1947, Електронний Архів Українського Визвольного Руху, http://avr.org.ua/ index.php/viewDoc/25253/ (17.02.2020).

[9] Сталинские депортации, 631.

[10] Vytautas Tininis, Sovietų Saįungos politinės struktūros Lietuvoje ir jų nusikalstama veikla: antroji sovietinė okupacija (1944–1953) = Poltical bodies of the Soviet Union in Lithuania and their criminal activities: the Second Soviet occupation (1944–1953) (Vilnius: Margi Raštai, 2008), 365.

[11] Polian, Against their will, 356.

[12] Сталинские депортации, 641.

[13] Tininis, Sovietų Saįungos politinės, 365.

[14] Указ Президиумa Верховного Совета СССР от 26 ноября 1948 года. Об уголовной ответственности за побеги из мест обязательного и постоянного поселения лиц, выселенных в отдаленные районы Советского Союза в период Отечественной Войны. – История сталинского Гулага, 585–586.