Remembering dictatorship in Hungary. An interview with Dorottya Baczoni of the House of Terror Museum

The ninth European Remembrance Symposium, entitled "Memory and Identity in Europe: Present and Future", took place in Tallinn on 26-28 October 2021. During the conference, we carried out an interview with a representative of the House of Terror that focuses on communist and fascist regimes in Hungary to ask questions about the museum.

Questions were answered by:

Dorottya Baczoni who first began working at the House of Terror Museum in 2009 before going on to serve as a staff historian from 2014 to 2016. Between 2018 and 2019 she was Head of the Department for Strategic Planning and Analysis at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade of Hungary. In 2019 she returned to the House of Terror Museum and since March 2021 she has been the director of the Institute of the Twentieth Century, which cooperates closely with the House of Terror Museum and is under the management of the same foundation. She is a doctoral candidate at Eötvös Loránd University.

CC.ORG: Would you mind telling us a little bit about the House of Terror?

The House of Terror Museum was opened in the heart of Budapest on February 24, 2002. Its mission was to introduce the visitor to the two subsequent totalitarian dictatorships which held Hungary in their grip for over four decades, starting from 1944.

Its existence has enabled us to take the interpretation of our history into our own hands after having been fed, for almost half a century, a single narrative which reflected the interests and the views of a foreign power. Setting up the House of Terror Museum thus reflected the need of our society to be in possession of our own past and consequently bring to the surface what happened to our nation over the past decades. After those things had been suppressed for such a long time, the Museum significantly contributed to a process whereby we could mourn our victims and process our traumas together.

Could you tell us more about the history of that building?

The Museum is situated in a symbolic site, at 60 Andrássy Avenue, an address which is, for all Hungarians, a synonym for terror, fear and oppression. In fact, the building was an epic site of two terrorist dictatorships from October 15, 1944, the date of the Arrow-Cross takeover well until the 1956 revolution. The apartment house built in the 19th century became first the headquarters of the pro-Nazi Arrow-Cross Party, then, in the wake of the Soviet occupation of Hungary, served – by no coincidence – for many years as the central building of the political police of the communist dictatorship. Thousands of people were kept prisoner, interrogated and tortured there for political reasons.

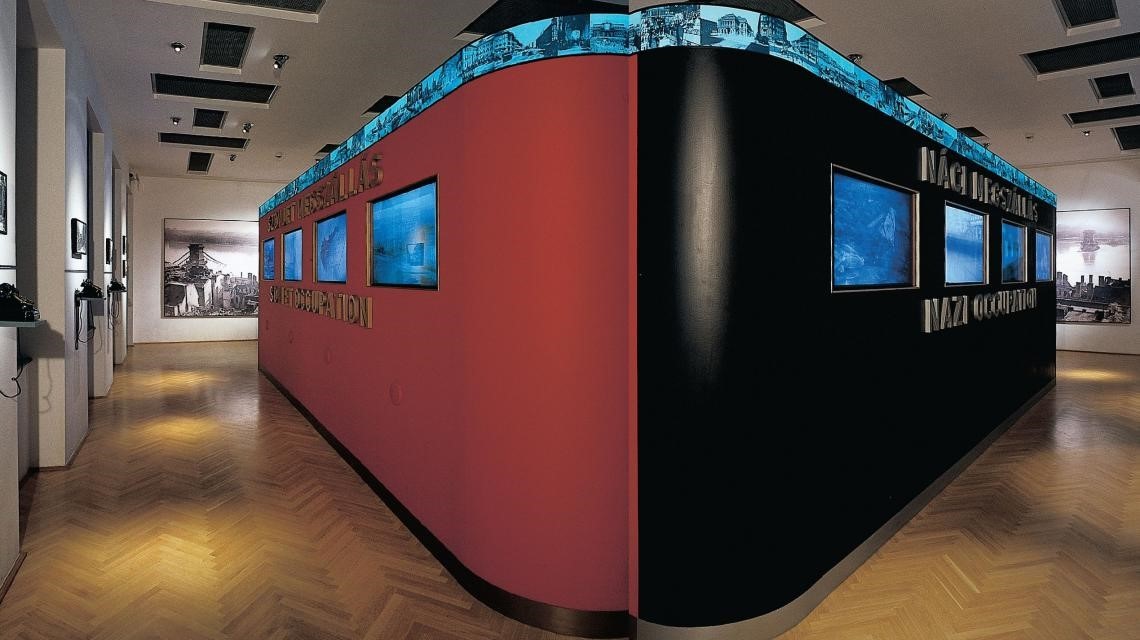

The mere fact that our institution was set up in such a historically significant building, instead of being built on an empty lot, carries an important message. It symbolises that we are capable of leaving the horrors of the past behind, closing them within the walls of the Museum while conserving them as a memento. The unique past of the building opens an opportunity to introduce the visitor to the continuous nature of the two dictatorships and the similarity of their methods in exercising power, while serving as the basis for a historiography represented by the Museum’s funding director-general Professor Mária Schmidt based on the theory of totalitarianism which treats those dictatorships as being related, puts them side-by-side, and points out their shared routes, similarities and shared characteristics. All this is expressed in the logo of the Museum featuring a five-point star and an arrow-cross. At the time when the Museum was inaugurated, this concept amounted to breaking a strong taboo, for it shed a radically new light on history.

The House of Terror describes itself as a museum and a memorial. Why? How is the Museum connected with the culture of remembrance in general?

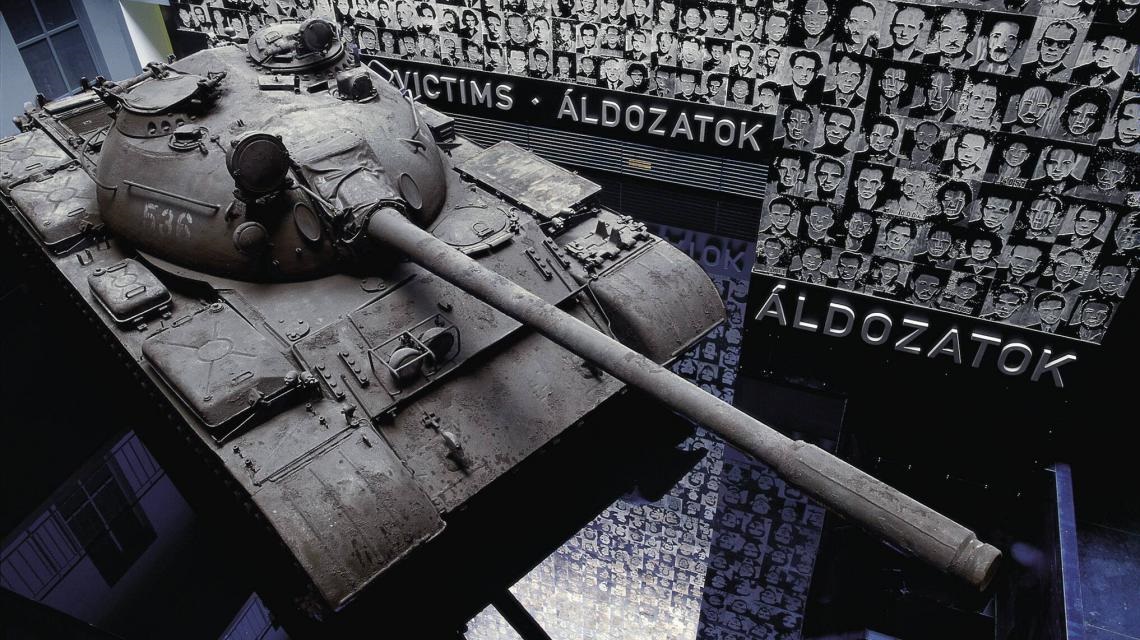

The symbolic nature of the building makes it a site of national remembrance. Apart from the historical exhibition itself, the institution is also a site of remembrance where people light a candle commemorating fellow Hungarians who were sent to concentration camps, deported, imprisoned, beaten to death, shot dead on the Danube bank, tortured, humiliated and intimidated. That function of the Museum is bolstered by the layout of its façade: the building is surrounded by a black frame isolating it from its environment and thus arousing the curiosity of the passers-by, while reminding for a moment all of them that the site of so much horror has by now become a monument to the victims.

Could you tell us more about how the Museum sheds light on the fascist and communist crimes of the past?

The exhibition covering three floors is framed by two dates – the starting point being March 19, 1944, when Hungary lost its sovereignty as a result of Nazi occupation, and the closing date being the 19th of June, 1991 when, with the last Soviet soldier having left its territory, Hungary regained its full sovereignty.

Visitors go through halls representing the Arrow-Cross dictatorship and then are introduced to the destructive reality of the communist one-party system extending to all spheres of life. They can feel being part of the trainloads of people heading for the Gulag; witness the bugging of conversations behind the scenes of communist propaganda; get introduced to the world of the political police, as well as the suffocating pressure of Soviet-type dictatorship on churches, the industry, agriculture, the judiciary, as well as everyday life.

Following their itinerary through the exhibition, visitors virtually descend into ever darker chapters of history, as the the exhibition starts on the second floor, from where we first reach the first floor then the basement, aboard an elevator whose deliberately slow motion causes us to emotionally prepare for the worst. Once downstairs, we find ourselves in a reconstructed version of the underground prison that once operated by the communist police under this building. It was built on the basis of recollections by survivors and copying details of underground prison systems elsewhere in the capital.

As for the representation of the history of the Holocaust, during its term (from 1998 to 2002), the first Orbán government decided to set up two institutions simultaneously, namely a Holocaust Museum and one representing the two totalitarian dictatorships. The Holocaust Documentation Centre and Remembrance Site was inaugurated two years after the opening of the House of Terror Museum, in 2004. The decision on setting up the two institutions clearly set separate missions to them, and thus, showing the details of the tragedy of our fellow Hungarians who fell victim to the Holocaust, was not part of the mission of the House of Terror Museum.

How do traumatic memories of political repression affect people’s views towards the corresponding historical events?

Public memory quite naturally associates the two totalitarian systems with open terror, since both the Arrow-Cross dictatorship and the communist regime of the 1950s based their domination on terrorising the population. One could hardly find one single family that remained unaffected, one way or another, by the oppressive machinery of the dictatorships.

Nevertheless, we must remain equitable, and the history of systemic political terror as presented in the House of Terror Museum starts with the Arrow-Cross takeover in Octorber 1944 and ends with the reprisals in the wake of the 1956 revolution and the last political executions in the early 1960s. The authors thus considered the era of communist terror as having come to an end at that point, distinguishing it from the subsequent periods of communist dominance. Thus, the exhibition doesn’t put in the same basket the ruthless terror of the early 1950s and the significantly different policies pursued by János Kádár’s regime in the 1970s and 1980s.

Going through the last hall representing the withdrawal of Soviet troops and the symbolic events of the regime change, visitors may leave with a sense of relief justified by the images indicating the present era – that of a democratic and free country.

How has the social memory of the 1956 revolution changed over time?

The 1956 revolution and war of independence is an outstanding chapter of our national history and, as such, a source of pride for all Hungarians.

Remembering it was, however, made impossible for decades by the regime led by János Kádár, who came to power as a result of Soviet armed intervention against the revolution itself. The official narrative that would remain in place, and would define the official discourse about the revolution well until the 1980s, was outlined as early as in December 1956. It claimed that 1956 was a counterrevolution aimed at restoring the pre-World-War-II regime.

Things were changing, however, in the 1980s – with people reviving the memory of 1956 and thus also confronting the Kádár regime as a whole. Unsurprisingly, the most crucial symbols and moments of the regime change were also linked to 1956 and the revolution. That unparalleled role of the revolution was also due to the fact that the memory of 1956 represented a positive tradition which all opposition forces could rely on.

The democratic states that came into existence as a result of the wave of anti-Communist revolutions that swept through the region made it possible to set up multiple narratives which were often competing with each other. This is what happened for 1956 as well, with a plurality of opinions and debates surging around it. No wonder, for society was 30 years late in processing and discussing those events. What was imperative was to overcome the unavoidable alienation of many people from 1956 as a result of the taboos of the previous decades and, instead, encourage people to consider the revolution as an intimate part of their own history. It is in that spirit that a memorial year was organised to celebrate the 60th anniversary in 2016 which was centred around the heroes of 1956 who could be held in high esteem by all Hungarians.

Recently, the Hungarian authorities have removed a statue of Imre Nagy, the martyred Prime Minister of the 1956 Revolution, from a square in central Budapest. Some say that the nationalistic government is revising the country’s history, and it is only one of many erasures. Why did Hungary remove the statue of I. Nagy, who was perceived by many as an anti-Soviet hero?

In fact, moving the statue of Imre Nagy, the Prime Minister of the revolution, to another site was not a decision related to the interpretation of his role in history. As part of a project to re-establish the pre-1944 image of the surroundings of the Parliament building, many other statues were also moved to other sites, including one erected under the first Orbán government.

The case of Imre Nagy’s statue was in no way different – it is now to be found in an equally central location not far from the Parliament building. As for his role in history, it is a complicated and divisive issue. For many, he in fact represented the hope of a better future and when refusing to renege on the revolution until his very death and then being executed, he became a martyr. Therefore, his figure became one of the main symbols of facing the nation’s past during the regime change.

Meanwhile, his figure being a central element during those months, helped strengthen a left-wing, reform-communist interpretation of the revolution, offuscating its other, more dominant currents and heroes. Many are inclined to forget about the total picture of his career – he was an authentic Communist politician who as a cabinet minister had actively contributed to building a communist dictatorship in his country, including the forcible collection of produce from Hungary’s peasantry.

The 2021 Symposium in Estonia took place 30 years after the dissolution of the USSR and the end of the Cold War. Please tell us, how did the communist rule in the People's Republic of Hungary come to an end in 1989?

Those changes were first of all the result of the will and action of the population. The changes in the Cold War rivalry between the two superpowers, the United States of America and the Soviet Union, as well as the wholesale and deepening crisis of the socialist economic system, were indispensable but not sufficient conditions for the countries of Central and Eastern Europe to become independent.

The various symptoms of a systemic crisis, as well as the unsustainability of the efforts of the Kádár regime to preserve the existing living standards, rapidly triggered a political and legitimacy crisis. By the end of the 1980s, the desire for change appeared with elementary force – a series of mass demonstrations in Hungary unequivocally showed that the overwhelming majority of the population had had enough of communism.

After having apparently been rocksolid for decades, the self-confidence of the ruling party was suddenly shaken. It is that pressure on the part of society that made it possible for talks between the representatives of the regime and the new forces of the opposition and put through a revolutionary regime change with peaceful means.

Historically speaking, the transition from a one-party system to a multi-party one, and from a centrally planned socialist economy to a welfare market economy, as well as from censorship to free press, was instantaneous. Leaving the Warsaw Pact and the Comecon behind, the Visegrád Four are now members of NATO and the European Union. That is a huge, shared success which fills us with pride. Quite naturally, those deep and complex changes also brought several new challenges, but that was a price undoubtedly worth paying.

You took part in a discussion on the subject of dealing with difficult pasts. Could you tell us more about what kinds of tools or practices can be used to help us to shed light on such issues?

There are two of them I would point out. The first one is the importance of emotional impact. If you find a way to reach people’s hearts, you will manage to open their minds as well. It is the emotional experience that leads one to actual intellectual openness. Sensual experience will lead to inclusion and arise interest. Therefore, the primordial goal the House of Terror Museum strived to achieve since its inception was triggering catharsis in the visitors and involving them in the processes represented in the exhibition.

It was particularly important to find a language, in terms both of visuality and content, that would reach young people. A second important factor is the role of history teachers. By now, it is almost natural for all classes of schoolchildren to pay a visit to the House of Terror Museum; many regularly attend our yearly special history classes, and tens of thousands of teachers attended lifelong training courses to which the Museum contributed by shedding a new light on various periods in history, including World War I, the 1956 revolution or, again, the transition to democracy in 1989/90.

You also mentioned that the Museum was at the heart of a vast controversy at the times of its opening in the 2000s. What were the issues then, and have they been resolved today?

The House of Terror Museum found itself in the eye of a political cyclone as soon as the decision had been taken to set it up and remained as one of the most important topics on the political agenda for years, although it addresses all Hungarians regardless of their political affiliations.

On the surface, the institution was engulfed in the feud among political parties, as a few months after it had been inaugurated, a new-liberal government was voted into power which saw in it a political symbol and tried to stifle it. Deep down however, what was at stake was much more than everyday politics: setting up and institutionalising a new historical narrative, as well as introducing a new rival view of history, something much more deep-going and far-reaching than just the usual political sword-rattling.

The real novelty that the House of Terror Museum represented was a new frame challenging the narrative reflecting the outlook of the victors of World War II, one representing events from a national viewpoint. The substance of that narrative emerges right in the first hall entitled Double Occupation which represents the continuity of the Nazi and then the Soviet occupation, framed by a red and black installation featuring archive footages. That very same continuity is also shown in the room dedicated to Changing Clothes in the centre of which two uniforms are shown, one of the Arrow-Cross militia and another one of the communist political police on a rotating platform, as if representing the two sides of the same coin.

The exhibit also sheds light on an important, often hushed up fact – the supporters of the two extremist ideologies and the officials of the two totalitarian regimes were often the same persons. All that had earlier been taboo.

The exhibition also considered it as its task to show those responsible for operating the machinery of the dictatorship – not as an end in itself, but as a means of confronting the past. Thus, the visitor may look into the eyes of the leaders of the one-time political police, the judges of a distorted justice system as well as the officials of the Arrow-Cross regime and of the Communist political police.

Unsurprisingly, the Wall of the Perpetrators erected at the end of the exhibition triggered huge echoes, as for the first time, the public was confronted with the names and the photos of those responsible for the two terrorist dictatorships. That symbolises the need to draw a sharp dividing line between perpetrators and victims, while expressing the Museum’s determination to reject the widespread idea of collective responsibility.

One of the most important achievements of the regime change was the idea that individuals can only be judged after their deeds – responsibility is individual and is not transferable. Many people, however, found that confronting such a past didn’t serve their interests, which was one factor in the sharp attacks on the Museum.

What projects will the House of Terror be working on next?

The House of Terror Museum will celebrate the 20th anniversary of its creation in February 2022 with a series of events and programmes. Our next temporary exhibition, on the other hand, will be dedicated to Margit Slachta, the first Hungarian woman who became a member of Parliament in 1920.