The March Deportation attempted to intimidate and ultimately Sovietise the Baltics

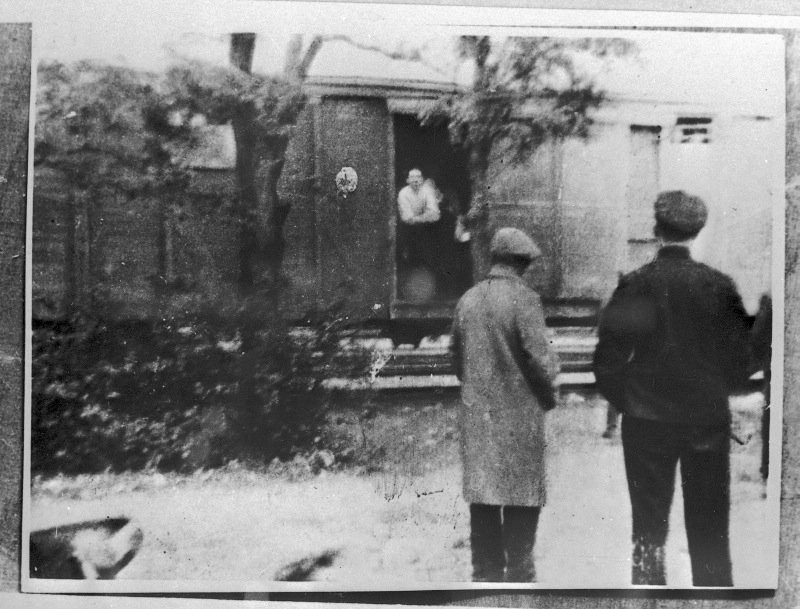

It had to begin suddenly, at dawn, when the children were still asleep. It had to blow people out of water like a breaking wave (deportation operation “Priboi” translates as “Coastal Surf”) and change their fate forever. Security officials had secretly readied themselves by the evening of 24 March in Vilnius, Riga and Tallinn to begin the man-hunt an hour after midnight.

Local activists considered loyal to the authorities had been assembled in community centres under the pretext of a spring sowing meeting or some other excuse. They had gotten wind of the expected "operation", so they waited for the command with mixed feelings in parish houses and other meeting points. Security officers divided them into task forces led by operational officials; the groups also included destruction battalion or “national defence” fighters and soldiers of the internal forces.

The latter had surrounded the assembly points to make sure that those present cannot leave and warn the victims. Loading points had been established in railway stations for the deportation trains, ready to place people in echelons. The general manager of the operation, USSR Deputy Minister of State Security lieutenant general Sergei Ogoltsov was in the HQ in Riga while the Soviet Republic leaders were in their local capitals. Major-General Ivan Jermolin, Deputy of the USSR Ministry of National Security, was ready to give the go-ahead in Tallinn. The lower link in the chain of command was in the county where the commissioners of the USSR Ministry of Security had been dispatched.

Preparations for Operation “Priboi” had started on 18 January 1949 after Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian SSR Communist Party’s local 1st Secretaries had met Stalin in Moscow. On 29 January 1949, Stalin signed a decree which ordered the permanent deportation of 29 000 families (altogether 87 000 people) from Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania to Siberia. This figure did not come out of the blue; it roughly corresponded to the number of breadwinners that were already accounted for, which had been tripled (considering the number of family members) to get the total number of people. Stalin appointed his deputy, Lavrentiy Beria, to be the coordinator of the preparations, as the Ministry of National Security and Ministry of the Interior played a key role in the proposed operation. In Lithuania, the top secret preparations started already on 7 February, Estonia and Latvia followed a bit later.

A BOOK ABOUT MARCH DEPORTATION PUBLISHED

The second volume of the collection “Proceedings of the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory” publishes the “Priboi” (“Coastal Surf”) files for the first time in Estonian. The files were classified by the Ministry of State Security and uncover the execution of the deportation in Estonia. In addition to documents, the book includes seven original articles on different aspects of the March Deportation. The articles analyse how deportations were organised in pre-war Soviet Union as well as the commemoration of victims of the March deportation nowadays.

“Priboi” Files: Articles and Documents of the March 1949 Deportation. Edited by Meelis Saueauk and Meelis Maripuu. Proceedings of the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory no. 2 (2019). Tartu, University of Tartu Press. 536 pp.

For each family or household that was to be deported, a separate file had to be drawn up and all families had to be secretly accounted for. Families largely fell into three categories. First, the “kulaks” with their families – farmers who were better off and employed workers, owned agricultural machines, or had been for some other reason taxed as a kulak since 1947 and burdened with higher taxes. The second major category included the Forest Brothers and their supporters – families of “bandits” in the eyes of the foreign regime.

The third category comprised unarmed persons involved in independence movements. In Soviet jargon, they were referred to as families of “nationalists”. The fact that most of the deported were women and children can be explained by the fact that there were no fathers, brothers and sons left in most of these families. They had been killed, imprisoned or gone into hiding in fear of the repressions. However, a decision was made to deport also the families of "legalised persons", aka those who had already come out of the forests.

The atrocious plan stipulated the confiscation of houses and other considerable property left behind by the deportees. Registering the property had to be undertaken by the same local activists who had led the task force into the farm. Therefore the locals – the main deportees – remember those persons and the myth that people deported themselves is persistent in memories.

The preparations for the deportation had been largely completed in Estonia by 15 March. In Lithuania it had concluded by 18 March. The operation commenced on the night of 25 March. In rural areas it started around 6 in the morning, but it did not go as smoothly as planned everywhere. The increased spying on people, large military gatherings and assembling transportation did not go unnoticed in a small “village society” like Estonia. Even during the operation, rumours of ongoing activity arrived before the task force. By the evening of the deportation’s second day, only three-quarters of the people who were to be arrested had been captured and the entire reserve had to be launched.

Contrary to Latvia and Lithuania, the aim of the deportation plan was not achieved in Estonia. According to even the most complete estimates, 20,713 people (92% of the objective) were deported from Estonia during the operation. All in all, 94,779 people were deported from the Baltic countries during the operation, which indicates that the initial plan was completed by almost 109%. Here and there, some resisted the deporters. A number of people gathered at the Keila loading point that had to be chased away.

Why was such a mass deportation even necessary? The most commonly named objective of the March Deportation and other similar post-war deportations is the attempt to eliminate the kulaks who hindered the collectivisation of agriculture. The principal desired outcome for the local administration here was "eradication of the kulaks as a class".

In reality, the Stalinist slogan overshadowed the broader aim of the deportation: complete sovietisation of rural areas. This involved suppressing resistance and liquidating the former village society (especially farm economy). Both had to contribute to the collectivisation process while silencing the independence movement and the Forest Brothers.

State-controlled farming had to make it difficult to provide food for the Forest Brothers. Intimidating those who stayed was also considered important. In fact, it affected both farmers and Soviet activists – everyone felt unsafe. This was despite the fact that by participating in the deportation, the latter had profoundly embarrassed themselves in the farmers’ eyes.

The March Deportation pursued the same purpose as most post-war mass deportations. They began in 1947 in Western-Ukraine with Operation “Zapad” (“West”) and lasted roughly until Stalin’s death. It is estimated that about 6 million people were deported in the USSR during Stalin's rule.

Some comparisons have been made between the 1941 and 1949 deportations. Both times the USSR prepared for war, and therefore attempted to prevent possible uprisings in its rear. USSR’s disagreements with the West had reached its climax by 1949. As we know, the confrontation led to the Korean War the next year.

How to evaluate the outcomes of the March Deportation? In a shorter perspective it largely corresponded to set goals: frightened country dwellers rushed to kolkhozes and desperate Forest Brothers were captured one after another within the following years. Executers of the operation received national recognition and decorations. In a longer perspective however, the March Deportation proved to be a major political mistake that filled a large part of the population with hostility and passive resistance.

This culminated with a demand to secede from the Soviet Union as soon as the opportunity arose. The wound could not be healed even with an otherwise well played resentment of Stalin's personality cult and terror during Nikita Khrushchev's tenure. The thaw was accompanied by a policy of reviewing repressions and the release of prisoners and deportees, which was largely implemented by 1960. Furthermore, the documents of those who had been in resettlement remained tainted and they had to endure various negative consequences and restrictions many years later.

Only time can alleviate the wound the deportation left in people’s souls. It must not be forgotten either. The March Deportation and other acts of communist terror are commemorated in Maarjamäe memorial in Tallinn, opened in 2018. Its memorial wall bears of the names of 3,000 people who died during the deportation or in resettlement. Hopefully, the recently published “Priboi” Files: Articles and Documents of the March 1949 Deportation, the second volume of the collection “Proceedings of the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory”, will support commemoration.