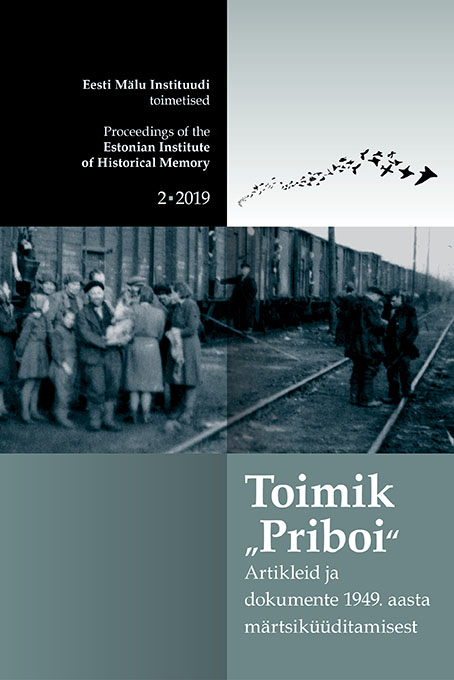

March Deportation. Arrival: „Slave Market“ and First Lodgings

Based on archival sources and memoirs, Aigi Rahi-Tamm, a historian, and Associate Professor of Archival Studies at the University of Tartu, describes the difficulties suffered upon arrival by the Estonian citizens who were forcibly deported to Siberia in March 1949. The March deportations were carried out based on the USSR Council of Ministers 1949 Decree No 390-138ss, pursuant to which 22,500 persons had to be deported from Estonia and a total of 87,000 from the three Baltic States together. They were labelled „kulaks“, „bandits“, „nationalists“ etc. and included the elderly and children.

The original article was published in the Proceedings of the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory 2, „„Priboi“ Files. Articles and Documents of the March 1949 Deportations“ (editors Meelis Saueauk, Meelis Maripuu, 2020). The book can be obtained from the University of Tartu Press online store or from regular bookstores.

The 19 echelons from Estonia were headed towards the Omsk, Novosibirsk, and Irkutsk Oblasts, and Krasnoyarsk Krai. Some groups were re-routed and ended up in the Kemerovo, Karaganda, Tomsk, and Magadan Oblasts, Habarovsk Krai and the Komi ASSR. According to the original plan a part of the deportees were to be sent to the Yakut ASSR, but because of bad transport connections this did not happen. However, eventually some Estonians ended up in Yakutia as well.

The biggest number of deportees from the Baltic States were taken to the Irkutsk and Omsk Oblasts, including four echelons from the Estonian Counties of Võru, Valga, Tartu and Viljandi. More Estonian deportees were sent to the Novosibirsk Oblast (nine echelons) and Krasnoyarsk Krai (six echelons). People were also moved around and resettled later, but it is difficult to know the numbers, given the chaotic recording of such movements.

Table 1. Destinations of the deportations from the Baltic states in 1949.

|

area |

families |

people |

%persons |

|

Krasnoyarsk Krai |

3671 |

13 823 |

14,7 |

|

Novosibirsk Oblast |

3152 |

10 064 |

10,7 |

|

Tomsk Oblast |

5360 |

16 065 |

17,1 |

|

Omsk Oblast |

7944 |

22 542 |

24,0 |

|

Irkutsk Oblast |

8475 |

25 843 |

27,6 |

|

Amur Oblast |

2028 |

5451 |

5,8 |

| Total number of deportees |

30 630 |

94 779 |

100,0 |

A commission consisting of the chairman of the Executive Committee of the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies (chairman of the commission), secretary of the Communist Party Raion Committee as well as the local UMVD (Управление МВД) leaders was established to receive, distribute, transport to the final destinations, and organise the accommodation of the deportees. The head of the UMVD was responsible for executing the decisions of the commission.

The distribution system used for deportees in Siberia was similar to that found in slave markets

Upon arrival, the echelon chief handed the deportees over to the representatives of the local commissions. The distribution of the deportees started to be called „slave market“. In addition to the military and officials, all sorts of inquisitive people had turned up to see the new arrivals, among them also such who were after their possessions. Many have said that their things got lost on the way or during reloading.

Once again, the deportees were told that they had been exiled for life in Siberia and that anyone trying to escape would be given a 20-year sentence and returned to the same raion after serving the sentence. The grounds for permanent exile were established by the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet decree, dated 26 November 1948. Under the decree it was possible to keep some groups of deportees in exile indefinitely, without the right to return to their former homes. Those who escaped from deportation sites or assisted the escapees were convicted under § 82 of the Penal Code of the Russian SFSR and had to serve 20 years in hard labour camps, although later a somewhat shorter sentence of ten years was used as well.

Administrative charges meant fines and/or detention.[1] Helle Viir, deported from Viljandi to the Novosibirsk Oblast has described her arrival as follows: The train must have arrived at Kargat in the evening of 6 April. We waited to be let off the train for several hours. Then we were taken by truck to a clubhouse and were ushered into a corner in a corridor. This is when we saw the nurse for the first time – handing out pills and taking the temperature of those who were ill. Then we were taken to the commandature. It was the first time when we were dealt with individually. Family members were invited in one by one, the passports were taken from those who still had them; many „had not brought the passport“ or „it had been taken from them earlier“ – but this did not cause any problems. The decision was read out aloud and we had to sign it: sentenced to exile for life, not allowed to return to previous place of residence, 20 years in hard labour camp for attempts to escape. There was no specific charge, the document just said: nationality – Estonian. My mother protested and was told, wait until you arrive, then write an application and things will be cleared up.[2]

Chairmen of the local kolkhozes and sovkhozes and occasional representatives of some industrial enterprises had gathered in the stations to get work force. Families with more members of working age were sought after, but also the weaker and frailer (small kids, the elderly and sick) had to be taken by someone.

We were taken to a large room with all our belongings, and the slave market started. This is what it really was. Just like gypsies buying horses – looking into your mouth and patting you on the back. They all wanted the best goods. They did not look upon the frail and weak favourably, they were considered extra burden. It was the young and the strong, the ones able to do hard work, they wanted. Technical and construction skills were in high demand as well: lorry and tractor drivers, blacksmiths etc. Nobody wanted me – a good-for-nothing „wannabe writer“. It was only because I was young, tall, and strong that they took me. Women were given sly looks, but once it became clear that they would also bring along two-three kiddies, the looks turned sour.[3]

The deportees from the Baltic States included 2,850 70+ single persons, 146 disabled persons and 185 children who had been deported without parents,[4] clearly not meeting the expectations for additional work force.

Once the selection process was completed, people started to be taken to their appointed locations – some to kolkhozes, some to sovkhozes, some closer and some to more faraway places. Many still had to travel a long way, but instead of being driven by lorries, tractors, horse-sleigh, or ox cart, they had to walk. It was springtime in Siberia – the snow was melting, the roads were potholed and muddy, the ice roads across the rivers were not safe anymore. The great Siberian rivers were flooding, and ice was breaking up. To get to our destination, the agricultural holding, we had to cross a river.

We were not allowed to linger until the waters calmed. We gathered up our belongings and waited. [...] Large open fishing boats seemed to appear from nowhere. They were rowboats. Somehow, they were held stable by the bank in the strong current so that we could get on board with our possessions. We were landsmen and this was our first time in a boat. We are all going to drown here, we thought. The stream was fast, water was swirling around the ice and threatened to enter the boat. We threw items overboard to make the boat lighter, so that water would not flood it. The boats were loaded in a hurry, not considering who ended up with whom in one boat. On the wide waters the boats lost sight of each other. I was in one boat with my sister Aime and some of our things, our mother in another with the rest of our belongings.[5]

This family was lucky to meet up again soon. But there were cases where the mother and her child were placed in different echelons altogether and were thus separated. Siiri Raitar (Karu) was deported as a nine-year-old child all alone to Buryatia and it took six months for her to be re-joined with her mother who had ended up in Novosibirsk. The mother only learned in exile that her daughter had also been deported.

The Laurits family, who were in the same wagon with the girl, took care of her and did not let her to be sent to the orphanage. Along with Siiri there were other unaccompanied children who were put on the train in Valga, e.g., Kalju Saar, aged eight and Lembit Mets, aged twelve. This was a blatant violation of the Regulations on Special Resettlement, pursuant to which it was prohibited to deport unaccompanied minors, terminally pregnant women, and sick individuals.[6]

Children separated from their parents, also in case the mother was sentenced to a prison camp, had to be placed in orphanages. The commission receiving the deportees had the obligation to provide accommodation and medical aid to the arrivals. During the next 30 days their temperature had to be taken and they had to be examined by a doctor. Although this kind of care was prescribed, it mostly did not happen. But people have vivid recollections of the sanitary treatment to which they were subjected in saunas and disinfection chambers.

„In one of the larger railway stations everyone was taken to the sauna. I cannot remember, how many wagons at a time, but the big washing room was crowded with men. Underwear was taken to a separate room, where it was treated with heat (to get rid of lice).“[7]

This is how Vaike, who was deported as a six-year-old from Viljandi County to the UstTarka Raion of the Novosibirsk Oblast, remembers it: People were deloused and washed in a sauna in Tatarsk. I fell asleep in a corner, supporting myself against my granny’s prosthesis. When I woke up, I was all alone. I started crying and went looking for my mother. I opened a door and there were soldiers in full uniform holding rifles with bayonets. I started shaking them and hitting them with my fists, demanding my mother. Then my mother, all naked, emerged from a cloud of steam, she had heard my shouting and tried to calm me down. I never got my wash that time.[8]

First lodgings of the deportees

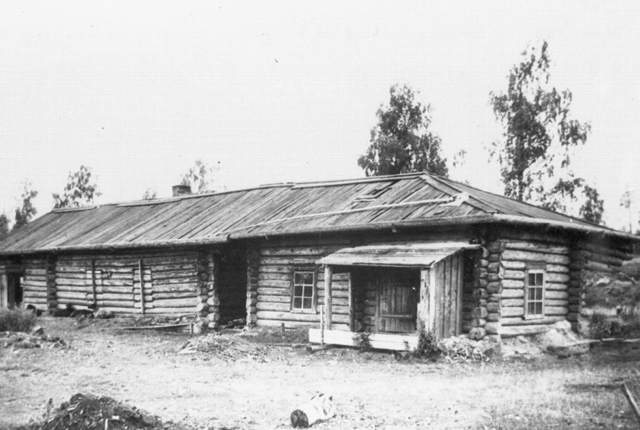

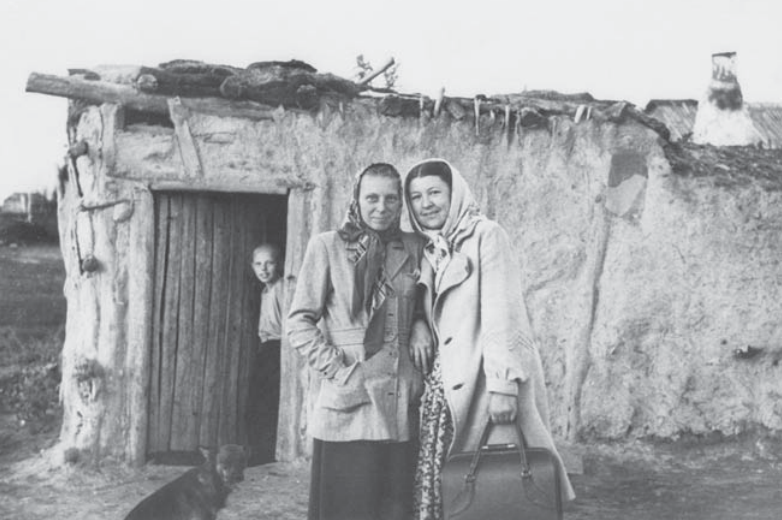

Initial impressions about the reality of a Siberian village and lodgings offered were really depressing. People were mostly accommodated in wooden shacks, mud or clay houses or other premises unfit for living. Many were lodgers with the locals who were living in tight conditions themselves. Later it emerged, that the local people had been threatened with punishment, should they refuse to take in the deportees.

Ahead of the arrival of deportees, campaigns were organised „for receiving re-settlers/members of kolkhozes from regions of the Soviet Union suffering from the lack of land (overpopulated regions)“.[1] Such campaigns shaped attitudes, the general mood and the relations between people. In order not to live in closed quarters, other options had to be sought. More active families tried to build their own mud or clay shacks in their first summer in Siberia, sometimes combining forces with other families.

Generally, accommodation remained a problem for years. The situation started to improve somewhat from 1951 and 1952. This is how Linda Kalamees, a deportee in the Cherlak Raion, Omsk Oblast, described the local building culture: the „house“, where we were placed was built of turf. It also had a turf roof. The house had two rooms. The was a large Russian stove in the front room, which also kept the back room heated. The same stove was used for cooking. The floors were covered with clay. […] The owners – husband and wife – were old, about 70. They slept on top of the stove. The stove was so big that four people could have slept there. We were given a wooden bed for sleeping. […] The Russians had the front room, which also served as the kitchen. We, i.e. I, my husband, daughter and another lady, Mrs Poolakene, lived in the back room. My husband had taken along two fur mattresses, one for our bed and the other one for our daughter, who spelt on the floor. Mrs Poolakene also slept on the floor.[10]

Aigi Rahi-Tamm (born 1965) has been Head of Archival Studies of the Institute of History and Archaeology at the University of Tartu since 2014 and Associate Professor of Archival Studies since 2021. She is member of the Commission on Examination of the Losses Inflicted on the Estonian Nation by Occupying Totalitarian Regimes. Rahi-Tamm has participated in many international projects and engaged in research in the Stanford University in the USA and University of Jena in Germany. She is the author of numerous publications in many scientific journals.

Sources:

[1] State Archives of the Russian Federation (Государственный архив Российской Федерации, (hereinafter: ГАРФ) Р-9479.1.611, 9–12. 12

[2] Estonian National Museum Archives, (hereinafter: ERM KV), Helle Viir.

[3] ERM KV, Uudo Suurtee.

[4] ГАРФ P-9479.1.475, 231–232.

[5] ERM KV, Helle-Mall Matlep-Truupõld.

[6] The author’s interview with Siiri Raitar, 15 March 2010 in Tartu.

[7] ERM KV, Ilmar Paunmaa.

[8] ERM KV, Vaike Kukk.

[9] 19 Государственный архив Новосибирской области (edaspidi ГАНО) 1030.1.44, 33 jj.

[10] ERM KV, Linda Kalamees