A Land of Plenty: American Press Coverage of the Holodomor

The article by Henry Prown, a Ph.D. student in American Studies at William & Mary College, examines the attitudes of US media towards the Soviet Union in the early 1930s. He argues that American journalists allowed themselves to be blinded by Soviet socialism and myths of economic prosperity or consciously chose a side in the ideological debate between capitalism and communism. The author shows that these trends are especially evident when discussing the Holodomor, a large-scale human-made famine that killed millions of people in the Ukraine, where attempts were made to silence the truth. This is a story of self-deception that should serve as a warning to those who tend only to see what dictators want to demonstrate to them.

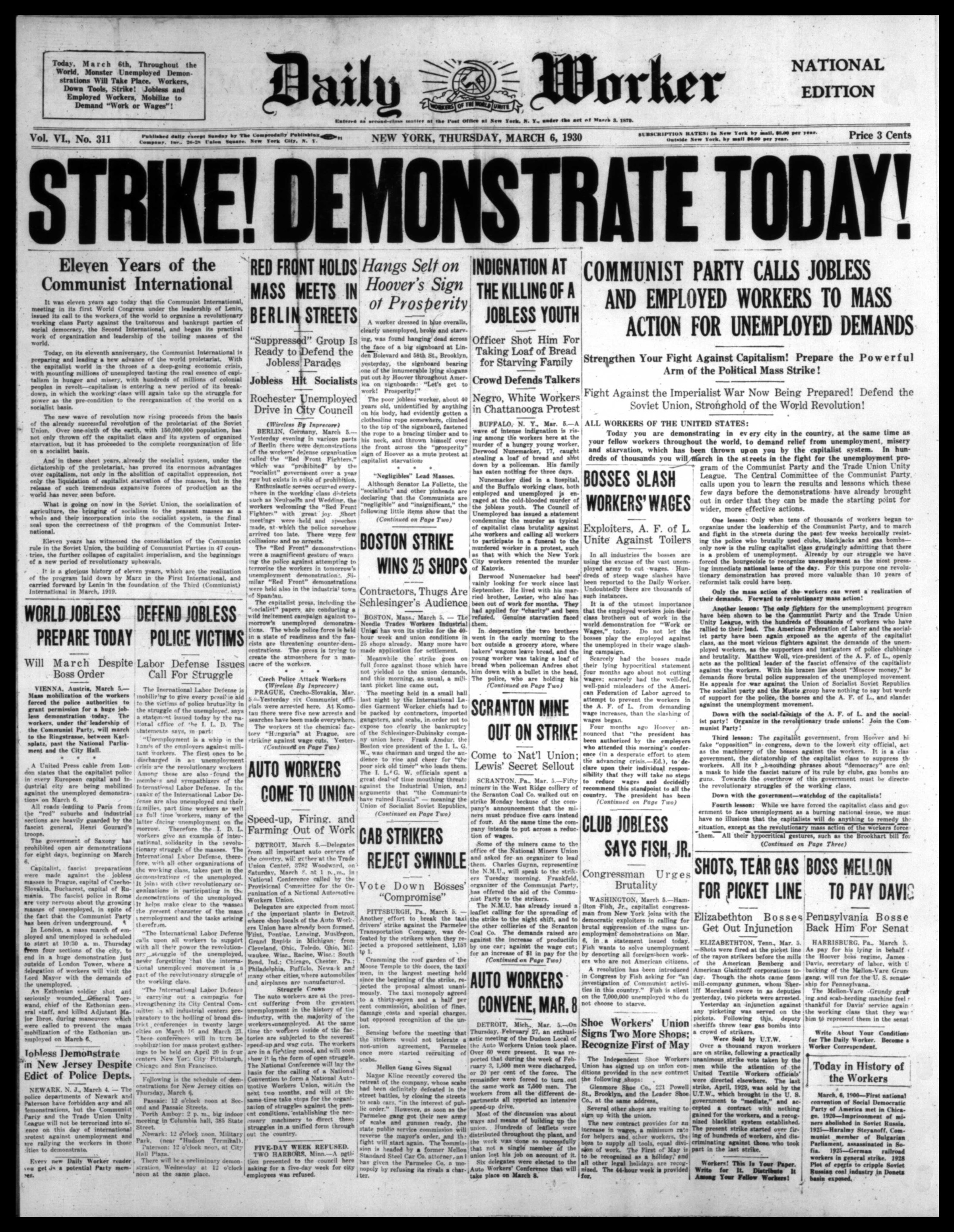

“Today, the truth is beginning to come out,” the leading article of the January 24, 1931 edition of the American Communist newspaper Daily Worker portentously proclaimed, “and the truth, the ghastly truth, is that famine and death hovers over hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions.” [1] The article referred not to a pending crisis in some far-away, foreign, poverty-stricken land but to the seemingly unthinkable threat of famine at home.

Even more ominously, the editors warned of an “effort to cover up…the crimes of the capitalist government,” which had apparently “deliberately and consciously insisted that starvation, death, pellagra and typhoid, be turned loose among the poor farming population.”[2] The authors went on to conclude that, in fact, “this situation is not famine – but murder, murder of the people by a government which no more represents their interests.[3]

Throughout the early years of the Great Depression, the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) repeatedly asserted that mass starvation was imminent. The organization’s journal, appropriately titled The Communist, scornfully noted that while “the [Capitalist] apparatus is technically able to supply all necessities of life abundantly to every member of society,” in practice “we have actual starvation among millions of workers.”[4]

Party pamphlets declared that “millions of men, women and children starve” and offered political solutions for “How to End Starvation.”[5] The Communists were not merely arguing that famine had struck the nation, but that the famine was deliberately caused by the government, rather than the consequence of natural causes —that is, it was man-made.

To a certain extent, their fears were justified. Widespread hunger and food insecurity did plague the United States throughout the 1930s, as iconic images of bread lines and dispossessed itinerant farmers attested to.

However, these proclamations of actual mass starvation had little basis in reality. Indeed, as one recent National Academy of Sciences study found, “during this period, mortality decreased for almost all ages, and gains of several years in life expectancy were observed for males, females, whites and nonwhite[s].”[6]

On the other hand, to purely focus on problems of factual accuracy in these articles and pamphlets is to largely misunderstand their purpose. Vladimir Lenin, the founder of the Bolshevik movement and first head of the Soviet Union, maintained from his early revolutionary years that “all-round propaganda and agitation, consistent in principle…is the chief and permanent task of Social-Democracy.”[7]

As a result, the official media outlets of the CPUSA, such as they were, geared themselves entirely around the production of propaganda. The party maintained an Agitation and Propaganda Commission, commonly known as AgitProp, under which their newspapers operated.

These newspapers, like the Daily Worker, were explicitly tasked with being the “the collective agitator and organizer of our Party and of the masses.”

These newspapers, like the Daily Worker, were explicitly tasked with being the “the collective agitator and organizer of our Party and of the masses.”[8] Seen in this light, these exaggerated claims of famine had a clear strategic purpose — to critically and sensationally expose what the party perceived to be a fundamentally defective Capitalist system and to subsequently bring about revolution. Furthermore, these claims served to highlight the supposedly stark contrast between the failing West and its flowering Communist counterpart in the East.

USSR was portrayed by the American media as a workers paradise

To American Communists, the USSR represented a veritable worker’s paradise and the making of a place of unmitigated equality and opportunity. Even as the rest of the world plunged into economic malaise and social unrest, the distant and enigmatic land that existed under the bold General Secretary Joseph Stalin resolutely plowed ahead with a “Five-Year Plan” — an unprecedented attempt to jump start the process of industrialization, agricultural mechanization, and collectivization in a largely agrarian nation.

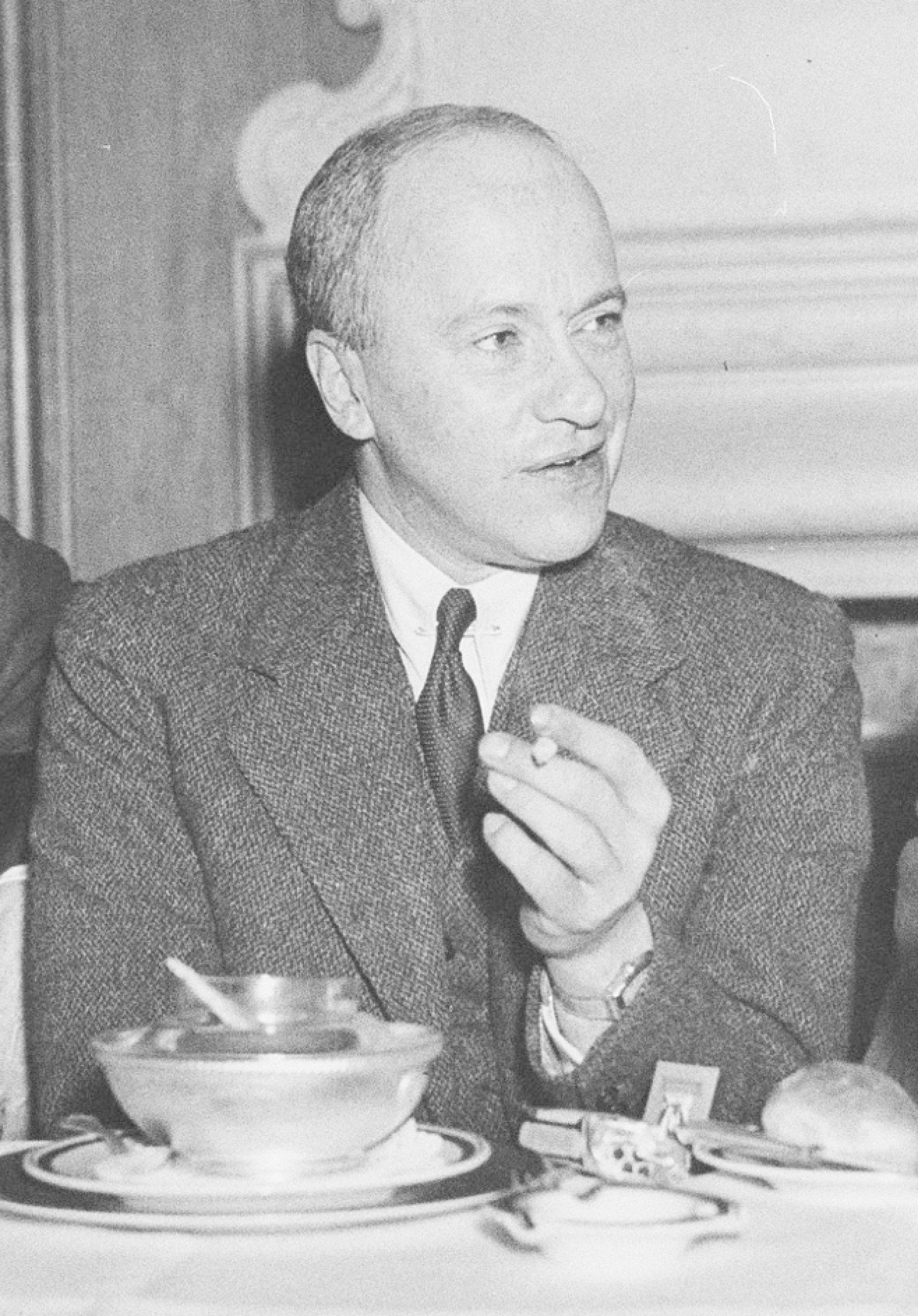

By all (Soviet) accounts, this effort wildly exceeded expectations, and the entire front-page of the January 28, 1933 issue of the Daily Worker was dedicated to Stalin’s celebratory report to the Central Committee on the “successes of the Five-Year Plan.”[9] CPUSA leader Earl Browder, in a typical fashion, declared before an American convention that:

“While living standards in the capitalist world took a catastrophic drop of 40 to 60 per cent, in the Soviet Union they leaped upward by more than 100 per cent. While capitalist policy is directed with all energy to cut down production in the face of growing millions of starving and poverty-stricken workers and farmers, in the Soviet Union the productive forces have been multiplied manifold, a half continent of 52 nations, of 165,000,000 population is being lifted out of poverty into material well-being and a rich cultural life.”[10]

These stark disparities in national conditions, as presented by the party, could not be plainer. As the specter of starvation purportedly stalked the formerly bountiful American heartland, the Soviets and their Eastern satellite parties offered an ever-growing spectacle of towering industrial achievements and astounding harvests. Many non-Communists agreed, and mainstream media outlets in the West would at times echo these positive evaluations.

One typical Associated Press headline that was published in papers across the U.S. read, “Analysis of 5-Year Program, Started in 1928, Sets Forth Great Strides in one of the Most Momentous Experiments in Present-Day History”.[11]These influential journalistic pronouncements, in turn, would have a profoundly influential effect on the lives of some individuals.

As Tim Tzouliadis recounted in his fascinating history of the little known tale of American migration to the USSR in the 1930s, The Forsaken: An American Tragedy in Stalin's Russia, thousands of people decided to “take a gamble on reports they read in newspapers of how Soviet Russia alone still had economic growth and jobs, and was planning a society that placed working-men at its very center, no longer merely the peripheral casualties of other men’s greed.”[12]

At the time, Walter Duranty, the Pulitzer Prize- winning Moscow bureau chief for the New York Times, excitedly predicted that “the Soviet Union will witness in the next few years an immigration flood comparable to the influx into the United States in the decade before the World War,” which he attributed to “the success so far of the five-year plan and, perhaps, to an even greater degree the distress in capitalist countries.”[13] His excessive predictions never did come true, though those few unfortunate Americans that did take these assessments at face value would suffer grave consequences — for all was not as it seemed.

A country of contradictions

On June 10, 1930 Mr. Duranty played host to a party of businessmen at the extravagant Savoy restaurant in downtown Moscow. The group included executives and engineers from the Great Northern Railway company, who had been commissioned by the Soviet government to inspect the nation’s railroads and recommend steps to modernize them. During these difficult years, dozens of Western corporations willingly made deals with the Soviet devil, selling their advanced industrial goods and expertise to the one country that could seemingly still afford it.

Among this well-heeled group, sat a rather unassuming man named Homer B. Bassett, secretary to the company’s president. Buried deep within the basements of William & Mary’s Special Collections archive is his personal journal from the visit — with rusted rings, tattered pages, and until now, previously unknown.

Duranty left very little impression on Bassett that night, who only noted that they had quite a “comfortable evening” — “there certainly was no evidence of a food shortage here,” he mused after a few days of similarly fine dinners.[14] However, unlike most of the foreign travelers who visited the USSR in those days, Bassett’s experience was not limited to fancy restaurants, well-maintained museums and historical sites, Potemkin villages, specialty hotels, and restricted social interaction with carefully selected government officials.

Bassett soon began to understand that for the average Soviet citizen, life was anything but comfortable.

Instead, with a mandate to review the almost incomprehensibly vast rail system of a country that spanned upwards of 10,000 km from west to east, he was able to travel to places that few foreigners ever had the opportunity to see. Bassett soon began to understand that for the average Soviet citizen, life was anything but comfortable.

In an abrupt change of tone, he quickly concluded that “there appears to be a shortage of almost everything…the people stand in long lines before the Government shops waiting for hours…everywhere one looks he sees these lines.”[15]

The whole environment felt off-putting, and small matters began to compound in his mind — he could not obtain a simple bar of soap, performers in a well-known orchestra at a concert he attended were bizarrely disheveled and unshaven, and posters, portraits, and busts of officials glared down at him menacingly as megaphones blared out government propaganda into the dreary streets. “The people,” he noted, “do not look happy and to date we have not seen a smiling face, most of the people looking careworn and as if they did not much care whether they lived or not.” [16]

As Bassett ventured deeper into the heartland, he grew to realize that just as Marxism was a theory of contradictions, the USSR was also a country of contradictions. He found an incomprehensible blend of things.

On the one hand, he witnessed arresting natural beauty, friendly, open, and charming locals, and amusingly bumbling local bureaucrats. On the other hand, he observed overwhelming and ever-present poverty, somber soldiers and security agents, and the terrifying sight of gaunt and harrowed prisoners locked in cattle cars across the tracks from his own luxurious private carriage

We were told that the reason for the food shortage is because the Soviet government tried to force the peasants into the collective farms.

Towards the end of the voyage, Bassett returned to Moscow where he soon befriended William Henry Chamberlin and his Russian wife. Chamberlin, a journalist for The Christian Science Monitor, was well known for his Soviet sympathies. However, in private conversations, he proved to be much more skeptical. “We learned many things of intense interest to us,” Bassett recalled. “We were told that the reason for the food shortage is because the Soviet government tried to force the peasants into the collective farms.”[17]

Perhaps more menacingly, Chamberlain and his wife informed Bassett that “the secret service, or G.P.U., reaches all corners of the country” — “Mrs. Chamberlain told us that they have to be extremely careful what they say to anyone.”[18] Bassett clearly took their words to heart, as he never published this insightful and revealing journal — instead bequeathing it to the university archive where it sat unseen for the last century.

The man who told the truth of Famine in Ukraine of 1932–1933

However, not all those who witnessed the evils of the Soviet Union kept their observations to themselves. Upon coming face to face with the complete obliteration of the traditional social organization of an entire class of people, their forced integration into untested collectivization units, and the mass exile of the most productive and energetic among them, some individuals foresaw the arrival of an imminent disaster.

After the Russian-speaking Welsh journalist Gareth Jones returned from a similar trip to the USSR in 1932, he posed the following question in a column for The Western Mail:

“‘Will there be soup?’ That is a question which the men and women of the Soviet Union are asking anxiously, dreadingly, when they think of the rigours of the coming Russian winter. It is a question which is being asked, not only in Communist Russia, but also in Capitalistic America: but in Russia the voices of the questioners are fraught with greater fear, because the harvest is failed and the food is not there.”[19]

Within a year these predictions of impending starvation, unlike those of the Communist writers at the Daily Worker, would tragically be proven correct. In historian Anne Applebaum’s recent and acclaimed English language account of the famine that followed these individuals’ observations, she provided an apt and concise summary: “at least 5 million people perished of hunger between 1931 and 1934 all across the Soviet Union… the famine of 1932–3 was described in émigré publications at the time and later as the Holodomor, a term derived from the Ukrainian words for hunger – holod – and extermination – mor.”[20]

Moreover, she charged that “starvation was the result, rather, of the forcible removal of food from people’s homes; the roadblocks that prevented peasants from seeking work or food; the harsh rules of the blacklists imposed on farms and villages; the restrictions on barter and trade; and the vicious propaganda campaign designed to persuade Ukrainians to watch, unmoved, as their neighbors died of hunger.” [21]In other words, Applebaum and others have compellingly argued that this particular famine was, to a large degree, man-made.

When Gareth Jones returned to the USSR that year, he illicitly travelled to the Ukraine, where he witnessed first-hand the events he had previously reported on, coming to fruition. Upon arriving back in the United Kingdom, he held a press conference on March 29, 1933 detailing his findings. “Millions are dying of hunger…everywhere was the cry, ‘there is no bread’,” he testified — this was “famine on a colossal scale.”[22]

A few days earlier, the British reporter Malcom Muggeridge had made similar claims in The Manchester Guardian. Soon, these scathing accusations were being reprinted throughout the U.S. as well, with publications like Times Magazine and the Washington Herald covering this unthinkable story.

Some authors were still diminishing the scale and significance of the famine

Damage control on the part of Soviet-sympathizing journalists and media outlets was swift. By March 31st, Walter Duranty had already cabled a now infamous rebuttal to his employer, The New York Times. He stated, “There appears from a British source a big scare story in the American press about famine in the Soviet Union”.

Duranty claimed that while “there is a serious food shortage throughout the country…there is no famine.”[23] In a follow up article titled “Soviet Industry Shows Big Gains”, he somewhat inexplicably asserted that the supposed increase in the production of industrial goods like automotive parts and tractors “is the most effective proof that the food shortage as a whole is less grave than was believed.”[24]

Naturally, Communist organizations in the West were even more aggressive in their denials. As I detailed in a recent article for the journal American Communist History about the Leftist literary magazine New Masses:

“The magazine presented the increasingly widespread accusation that a serious famine had stricken the USSR, in particular the Ukraine, as a baseless attack on the part of the capitalist press. A variety of New Masses reports from the years 1934 and 1935 refer to ‘the supposed famine of 1932-33,’ to ‘Hearst newspapers blazed with tales of famine and cannibalism’, to the ‘poverty and famine’ of the Soviet Union’ (note that ‘poverty and famine’ were deliberately placed in quotation marks), to the ‘the usual innuendos about bureaucracy, famine,’ and to ‘talks about starving Russia and Ukraine, in the face of such overwhelming evidence of Soviet advance.’”[25]

After all, as Anne Applebaum explained, “in the official, Soviet world the Ukrainian famine, like the broader Soviet famine, did not exist…it did not exist in the newspapers, it did not exist in public speeches…the response to the 1933 famine was total denial, both inside the Soviet Union and abroad.”

The fact that these partisan outlets took this position may not be surprising to readers. After all, as Anne Applebaum explained, “in the official, Soviet world the Ukrainian famine, like the broader Soviet famine, did not exist…it did not exist in the newspapers, it did not exist in public speeches…the response to the 1933 famine was total denial, both inside the Soviet Union and abroad.”[26]

The response of more mainstream American media outlets has been subject to sharper criticism. As early as 1937, Eugene Lyons, who had been a Moscow correspondent for the United Press, uncomfortably recalled that “throwing down Jones was as unpleasant a chore as fell to any of us in years of juggling facts to please dictatorial regimes – but throw him down we did…poor Gareth Jones must have been the most surprised human being alive when the facts he so painstakingly garnered from our mouths were snowed under by our denials.”[27]

Homer B. Bassett’s friend, a railway employee named William Henry Chamberlain, similarly repudiated rumors of famine as they appeared and then later renounced his own repudiations. Chamberlain’s book, Collectivism: A False Utopia, was published in 1937 and concluded that “millions perished of outright hunger and the diseases, such as typhus and influenza, that follow in the wake of hunger, during the great famine of 1932-1933, which was brought on by ruthless requisitions and colossal blunders in the administration of the collective farming system.”[28]

More recently, the 2019 film Mr. Jones dramatized the story of Gareth Jones’s attempts to alert the world to the horrors of the Holodomor. Walter Duranty is mercilessly lampooned as a sexual degenerate and a slavish Soviet lackey and, curiously for the American audience, the press mogul William Randolph Hearst is portrayed in a somewhat positive light. Hearst and the media empire he created is generally regarded as the epitome of media misconduct — the progenitor of “yellow” journalism, the megalomaniac protagonist of Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane, and the controlling monopolist who forced his views upon his editors.

As the journalist Ernest L. Meyer famously put it, “in his incendiary campaign[s] he has printed downright lies, forged documents, faked atrocity stories, inflammatory editorials, sensational cartoons and photographs and other devices by which he abetted his jingoistic ends.”[29] However, Hearst did, as the film detailed, publish Jones’s writing at a time in 1935 when he had lost favor with the British media establishment. These articles, which were some of the first to use the phrase “man-made famine” to describe the 1932-1933 famine, were also his last. Soon after his articles were published, Jones was murdered in mysterious circumstances at the Soviet border with Manchuria, and his story would be largely forgotten until the descendants of the people most affected by the famine brought his memory back to life in the decades that followed the fall of the USSR.

“The crisis which finds 10,000,000 jobless and starving in a land of plenty,” the Daily Worker mused on May 22, 1931, could not help but be compared to “the startling anomaly in the land where the workers and the peasants rule, where three [sic] are no idle starving workers, where the dynamo of the Five Year Plan, with [sic] its gigantic output makes the capitalists of the world tremble.”[30]

Even as these words were being written, however, this country was in the process of crushing its peasants under the pressure of mass collectivization, mass imprisonment, mass exile, and, finally, mass starvation. Despite these claims, the paper did not miss a beat. In a typical fashion, its leading editorialist, Michael Gold, wrote on January 29, 1935 that “the truth about the famine is that there was no famine.”[31]

Indeed, “it is a sign of the success of the workers’ republic, the Soviet Union, that the capitalists can fight it only with lies…truth, today, is revolutionary.”[32] That these capitalist liars, and more importantly the intrepid journalists whose reports they published, were eventually vindicated perhaps matters little. What may be more thought-provoking, from a modern perspective, is the degree to which our own media environment mirrors that of the 1930s. Concerns over “Fake News” and controlling corporate monopolies and foreign influence are by no means new, but rather inherent in mass media in general.

It may not be so much that truth is revolutionary, as Michael Gold once said, but that defining truth is. Those who have the ability to control historical narratives are immensely powerful, and power can be abused. This, more than anything else, is the message that one should consider when analyzing the rather obscure debate surrounding the terrible tragedy that took place in the Soviet Union, a world away and nearly a century ago.

Henry Prown is a PhD candidate in American Studies from the College of William & Mary. His previous work published on the portal brings to light the faith of Americans in Soviet prison camps.

Sources

[1] “The Hunger Government,” Daily Worker, January 24, 1931, p. 1.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] “Social Demagogy,” The Communist, February 1931, p. 99.

[5] Communist Party of the United States Pamphlet, "How to End Starvation," 1931-1935, TAM 124, Box 9, Folder 1, Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York, New York, United States.

[6] J. A. Tapia Granados and A. V. Diez Roux, “Life and Death during the Great Depression,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106, no. 41 (October 13, 2009): p. 17292, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0904491106.

[7] V. I. Lenin, Lenin Collected Works, vol. 5 (Moscow, Soviet Union: Progress Publishers, 1960), p. 20-21.

[8] J. Peters, The Communist Party: A Manual on Organization (New York, New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1935), p. 78.

[9] Joseph Stalin, “Results of the First Five-Year Plan,” Daily Worker, January 28, 1933, p. 1.

[10] Earl Browder, Report of the Central Committee to the Eighth Convention of the Communist Party of the U.S.A. (New York, New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1934), p. 5-6.

[11] Associated Press, “Soviet Industrial Plan May Take But 4 Years: Analysis of 5-Year Program, Started in 1928, Sets Forth Great Strides in One of Most Momentous Experiments in Present-Day History.,” The Washington Post, December 1, 1930, p. 1.

[12] Tim Tzouliadis, The Forsaken: an American Tragedy in Stalin's Russia (New York, New York: Penguin Books, 2008), Chapter 1.

[13] Walter Duranty, “MOSCOW EXPECTS IMMIGRATION SOON: Slight Influx of Workers From Europe and America Held Precursor of Movement. SKILLED LABOR IS NEEDED But Conditions Now Are Too Hard for All but Enthusiasts, Though Gains Are Planned. American Group Increases. Offers Citizenship Quickly.,” New York Times, February 5, 1931, p. 10.

[14] Personal Diary from Trip to the Soviet Union, May-September 1930, MS 00192, Box 1, Folder 3, Special Collections Research Center at William & Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia, United States, p. 6.

[15] Ibid, p. 7.

[16] Ibid, p. 6.

[17] Ibid, p. 45.

[18] Ibid, p. 46.

[19] Gareth Jones, “Will There Be Soup? Russia Dreads the Coming Winter,” The Western Mail, October 15, 1932.

[20] Anne Applebaum, Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine (New York, New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2017), “Preface.”

[21] Ibid, “Epilogue: The Ukrainian Question Reconsidered.”

[22] H. R. Knickerbocker, “Famine Grips Russia Millions Dying, Idle on Rise, Says Briton: Gareth Jones, Lloyd George Aid, Reports Devastation,” New York Evening Post, March 29, 1933, p. 1.

[23] Walter Duranty, “RUSSIANS HUNGRY, BUT NOT STARVING: Deaths From Diseases Due to Malnutrition High, Yet the Soviet Is Entrenched. LARGER CITIES HAVE FOOD Ukraine, North Caucasus and Lower Volga Regions Suffer From Shortages. KREMLIN'S 'DOOM' DENIED Russians and Foreign Observers In Country See No Ground for Predictions of Disaster.,” New York Times, March 31, 1933, p. 13.

[24] Walter Duranty, “SOVIET INDUSTRY SHOWS BIG GAINS: Output of Coal, Oil, Autos, Iron, Locomotives and Tools Is Up 20 to 35 Per Cent. PRODUCTION COSTS CUT Spring Sowing Progress Compares Favorably With Last Year, Despite Food Shortage.,” New York Times, April 6, 1933, p. 13.

[25] Henry Prown, “Famine, Trial, War: A Selected Review of Political Commentary in the New Masses from 1933 to 1939,” American Communist History 18, no. 3-4 (February 2019): pp. 296-309, https://doi.org/10.1080/14743892.2019.1682455, p. 301.

[26] Anne Applebaum, Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine (New York, New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2017), “The Cover-Up.”

[27] Eugene Lyons, Assignment in Utopia (New York, New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1938), p. 575.

[28] William Henry Chamberlin, Collectivism: a False Utopia (New York, New York: Macmillan, 1938), p. 90.

[29] Donald Langmead, Icons of American Architecture: from the Alamo to the World Trade Center (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood, 2009), p. 194.

[30] Harriett Silverman, “STATE AUTHORITIES IN N.Y. TELL UNEMPLOYED TO STARVE,” Daily Worker, May 22, 1931, p. 2.

[31] Michael Gold, “Change the World!,” Daily Worker, January 29, 1935, p. 5.

[32] Ibid.

Bibliography

Applebaum, Anne. Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine. New York, New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2017.

Associated Press. “Soviet Industrial Plan May Take But 4 Years: Analysis of 5-Year Program, Started in 1928, Sets Forth Great Strides in One of Most Momentous Experiments in Present-Day History.” The Washington Post. December 1, 1930.

Browder, Earl. Report of the Central Committee to the Eighth Convention of the Communist Party of the U.S.A. New York, New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1934.

Chamberlin, William Henry. Collectivism: a False Utopia. New York, New York: Macmillan, 1938.

Duranty, Walter. “MOSCOW EXPECTS IMMIGRATION SOON: Slight Influx of Workers From Europe and America Held Precursor of Movement. SKILLED LABOR IS NEEDED But Conditions Now Are Too Hard for All but Enthusiasts, Though Gains Are Planned. American Group Increases. Offers Citizenship Quickly.” New York Times. February 5, 1931.

Duranty, Walter. “SOVIET INDUSTRY SHOWS BIG GAINS: Output of Coal, Oil, Autos, Iron, Locomotives and Tools Is Up 20 to 35 Per Cent. PRODUCTION COSTS CUT Spring Sowing Progress Compares Favorably With Last Year, Despite Food Shortage.” New York Times. April 6, 1933.

Duranty, Walter. “RUSSIANS HUNGRY, BUT NOT STARVING: Deaths From Diseases Due to Malnutrition High, Yet the Soviet Is Entrenched. LARGER CITIES HAVE FOOD Ukraine, North Caucasus and Lower Volga Regions Suffer From Shortages. KREMLIN'S 'DOOM' DENIED Russians and Foreign Observers In Country See No Ground for Predictions of Disaster.” New York Times. March 31, 1933.

Gold, Michael. “Change the World!” Daily Worker. January 29, 1935.

Granados, J. A. Tapia, and A. V. Diez Roux. “Life and Death during the Great Depression.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106, no. 41 (October 13, 2009): 17290–95. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0904491106.

Homer B. Bassett Papers, MS 00192. Special Collections Research Center at William & Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia, United States.

“The Hunger Government.” Daily Worker. January 24, 1931.

Jones, Gareth. “Will There Be Soup? Russia Dreads the Coming Winter.” The Western Mail. October 15, 1932.

Knickerbocker, H. R. “Famine Grips Russia Millions Dying, Idle on Rise, Says Briton: Gareth Jones, Lloyd George Aid, Reports Devastation.” New York Evening Post. March 29, 1933.

Langmead, Donald. Icons of American Architecture: from the Alamo to the World Trade Center. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood, 2009.

Lenin, V. I. Lenin Collected Works. 5. Vol. 5. Moscow, Soviet Union: Progress Publishers, 1960.

Lyons, Eugene. Assignment in Utopia. New York, New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1938.

Peters, J. The Communist Party: A Manual on Organization. New York, New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1935.

Prown, Henry. “Famine, Trial, War: A Selected Review of Political Commentary in the New Masses from 1933 to 1939.” American Communist History 18, no. 3-4 (2019): 296–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/14743892.2019.1682455.

Sam Darcy Archives, TAM 124. Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York, New York, United States.

Silverman, Harriett. “STATE AUTHORITIES IN N.Y. TELL UNEMPLOYED TO STARVE.” Daily Worker. May 22, 1931.

“Social Demagogy.” The Communist, February 1931.

Stalin, Joseph. “Results of the First Five-Year Plan.” Daily Worker. January 28, 1933.

Tzouliadis, Tim. The Forsaken: an American Tragedy in Stalin's Russia. New York, New York: Penguin Books, 2008.