Communist crimes in Slovenia: mass graves and public discussion

1. Introduction

Around 130 000 persons, mostly political and military opponents, were executed after the end of the Second World War in May and June 1945.

Among the 130 000 were people who had managed to escape to Austria, but were handed over to Yugoslavia by the British Army, as well as opponents of the regime who had been captured by the Communists on Slovenian territory.

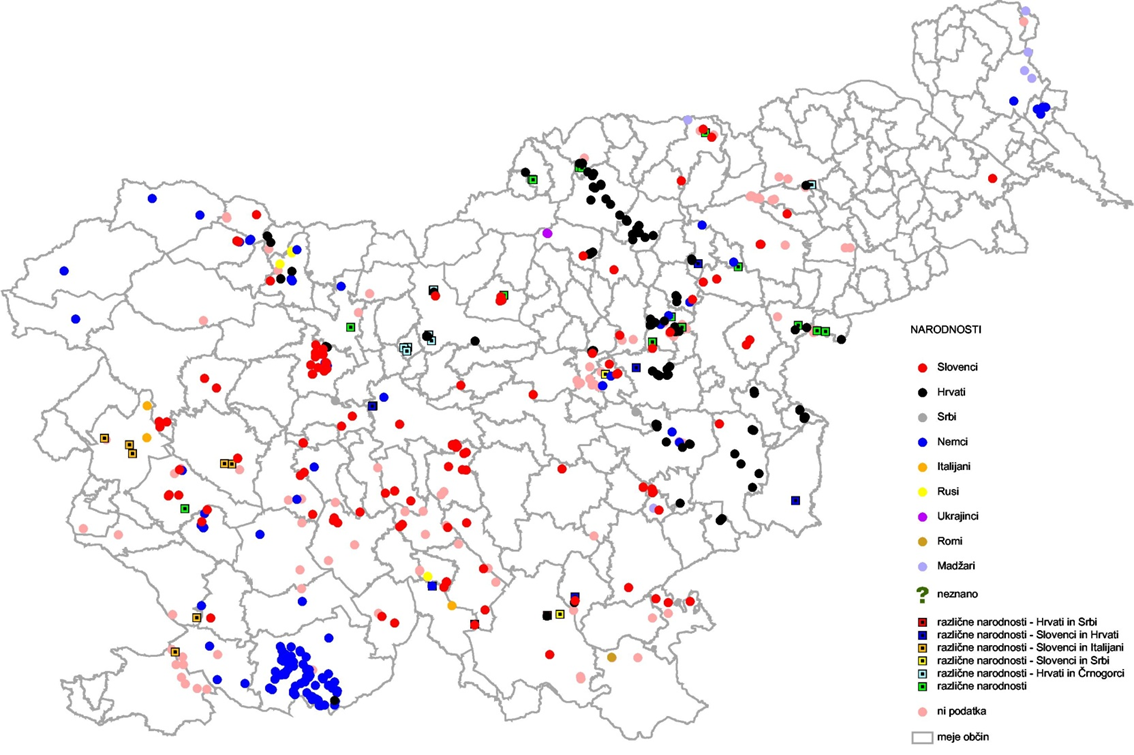

15 000 of those executed were of Slovenian nationality, whereas others included mostly Croats, Serbs and Germans. They were mostly civilians but also included members of the Slovenian Home Guard and other political and military opponents of the resistance movement.

These extrajudicial executions were carried out by the members of the Yugoslav Communist Secret Police and were committed at hidden locations across Slovenia, predominantly rural areas and forests. In May 1945 thousands of soldiers and civilians from all over Yugoslavia were on the run through Slovenia, headed north to freedom.

The Commission of the Government of the Republic of Slovenia on Concealed Mass Graves in Slovenia has recorded more than 720 hidden mass graves thus far. The Commission strives for exhumation, identification, DNA analysis and decent re-burial of all Slovenian victims killed on Slovenian territory.

While over 720 mass graves have been discovered in Slovenia by now, not a single communist war criminal has yet been sentenced.

On March 2009, one of the largest murder sites of unarmed people after the Second World War (estimated 3500 victims) was found in an abandoned mine called Huda Jama – Cave of Evil.

2. Procedure of locating, researching and exhumation

Procedure of locating, researching and exhumation is legally determined in different legal acts, e.g. The Criminal Procedure Act, The Concealed War Gravesites and Victims Burial Act, The Cultural Heritage Act and the Protocol of the Procedure of Excavating a War Gravesite.

Locating a mass grave is usually based on oral sources, mostly testimonies of witnesses or relatives of the victims. After that, test pitting can be carried out. The test pits are performed mechanically or by hand in an area of 1 x 1 m or 0.5 x 2 m, to the depth of uncovering any human remains. If human remains are found, all works immediately stop. An anthropological or a forensic expert comes to the site to determine if the bones are human. After the examination, police begin to investigate whether the grave is a result of a criminal offence.

If it appears to be a war or an after war grave, a state prosecutor may, on the basis of a crime report by the police, file an application with the competent court for an investigation to be initiated and propose that the investigating judge carries out an investigative act to obtain evidence. “On the one hand there is police investigation and legally defined criteria for carrying out an exhumation; on the other hand, an exhumation to satisfy the wishes of the victims′ relatives for a proper burial.” […] “We realized very early that such work requires the presence of archaeological experts…”

The Cultural Heritage Act considers everything older than 50 years archeology. Under the Criminal Procedure Act, a court-appointed medical expert of the Institute of Forensic Medicine at the Faculty of Medicine in Ljubljana is responsible for the physical act of exhumation of human remains under an investigating judge's order.

The expert will perform the necessary procedures for the police and court. From here on The Government Commission on Concealed Graves may adopt a proposal for a decision of exhumation and reburial of the remains found in a war grave. On the basis of this proposal, the Government can decide if there is sufficient public interest for the Ministry of Economic Development and Technology to finance and lead the procedure of excavation, or to co-finance the excavation with other entities that have a legitimate interest.[1]

In the end, the mass graves are protected, marked with a Christian cross and enrolled in the Register of the War Grave Sites and in the Register of Cultural Heritage Sites. From now on the Ministry of Labour is responsible for maintaining (e.g. technical maintenance, lawn mowing etc.) the war grave site.

3. Problems and perspectives

The problems concerning mass graves can be divided into operational-technical problems and obstacles and into broader substantial narrative problems.

The fact is that Slovenia is the only EU country that has never carried out lustration. The Slovenian parliament was not capable of accepting the European Parliament resolution of 2 April 2009 on European conscience and totalitarianism, nor has it condemned communism as a totalitarian regime, despite the fact that more than 130 000 victims on Slovenian territory were not able to prosecute and legally condemn a single perpetrator of the communist mass killings or other forms of political violence.

In the contrary, Slovenia is nowadays facing the problem of the revival of communist symbols. Those facts illustrate the essence of the problematic narrative and mentality of the predominant political left in dealing with the communist past in Slovenia.

Operational-technical problems are mainly related to the DNA samples that are recommended to be taken from the human remains in situ. We were not able to establish an effective system of giving and storing the DNA material of the possible relatives for subsequent analyses. Further problems are related to the items found in mass graves which should be preserved in museums. However, museums are sometimes reluctant to take and store such objects and use them as a museum exhibits.

We are also facing opposition to bury the Roma victims killed in 1942 by the Slovene communists in the central graveyard of the capital Ljubljana. The tenuous excuse is that there is not enough space at the cemetery. The real obstacle is that Ljubljana has been called “A Hero Town”, and the mayor of Ljubljana has unofficially said that collaborators have no place to be buried here.

The Government Commission on Concealed Mass Graves cannot reach and develop its full potential. Division of competences among three different ministries and dozens of institutions present the main obstacle for carrying out an efficient and quick procedure regarding the location, excavation, identification and decent reburial of the victims’ human remains.

The perspective is to upgrade and establish a more effective system with a new National Institute for dealing with public mass graves, which would contain all necessary human resources, knowledge and executive competences in one place, comparable with other successful institutes around the world.

Article is based on the presentation by Mr Kolarič at the international conference "Necropolis of Communist Terror".

[1] See more: Pavel Jamnik, Inclusion of Archelogy in Criminal Investigations – Slovenia, pp. 165-172. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/300917028_Inclusion_of_Archaeology_in_Criminal_Investigations_-_Slovenia.