Behind the Iron Curtain. Regulation and Control of the Border Regime in the Estonian SSR. Part 1

After it was illegally annexed by the Soviet Union in 1940, the formerly independent Republic of Estonia became known as the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic (ESSR), one of fifteen Union Republics of the Soviet Union. After a brief period of occupation under Nazi Germany from 1941 until 1944, Estonia remained firmly within the Soviet sphere until the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. Like the rest of the Union Republics, the ESSR was a closed society, being kept carefully detached from the world outside Soviet borders by the Soviet state. In this two-part article, Estonian historian Indrek Paavle investigates how the border regime in the Soviet Union was organized, using the ESSR as a case study.

Part 1 deals with the origins of the border regimen in Soviet Estonia, the various legislations that were enacted to ‘protect’ Estonians from the outside world, how the border was geographically defined, and what exceptions and exemptions were made in who had access to zones in the immediate vicinity of the border.

Part 2, to be published at a later date, will address the functions of various Soviet institutions as they applied to border policy, what punishments existed for border violators, relations between local residents and the border guards, and how Estonia’s hard border with the rest of the world finally came to an end.

This article is previously published in a memorial collection “At the Will of Power. Selected articles”. it contains the most important and best part of his research. The book can be purchased online from the National Archives of Estonia, Apollo and Rahva Raamat.

One of the main traits common to all communist regimes was the sealing off of state borders from the outside world. This meant restricting both entry into and departure from the country. Communist governments insulated their citizens from the outside world, attempting to isolate them from foreign influences. Such external influences, it was believed, represented a threat to the privileged positions of the communist leadership.[1]

While a passport is ordinarily needed only for travelling abroad, Soviet citizens were universally required to carry passports for travel within the borders of the Soviet Union. Similarly, while visas are generally issued to foreigners visiting a particular country, a visa was also required to leave the Soviet Union.

The mechanisms for confining citizens within Soviet borders was refined to perfection by the Soviet Government during the initial years of the Cold War, when the confrontation with the West led to the regime’s desire to severely restrict its citizens’ contact with the outside world. Opportunities for Soviet citizens to go abroad were reduced nearly to zero, and the regime’s paranoia culminated in a law enacted in 1948 banning Soviet citizens from marrying citizens of foreign countries.

This ban was repealed after Stalin’s death in 1953, but other means of control devised and implemented in the Stalinist era remained in effect until the Soviet collapse in 1991, sometimes fluctuating according to the Soviet political climate at a given point in time. Methods for sealing off the borders were no exception here.

Historical literature has paid little attention to the subject of Soviet state border regulation. The aim of this article is to identify how the border regimen in effect in the Soviet Union was organized, using the ESSR as a case study. Several pieces of legislation that applied throughout the Soviet Union, as well as some ten pieces of legislation particular to the Estonian Soviet republic, formed the basis for this regimen. This legislation was continually being supplemented, and the regimen was implemented through a large number of secret or restricted access directives and instructions.

I will attempt to analyse the changes that took place in the system, the reasons for those changes, and their effect on the population by examining the chronology of the legislation that regulated the border regimen. I will also consider the implementation of general legislation, or in other words, the border regimen permit policy, methods of control, and penal policy, to the extent that available sources permit.

Legislation and restricted access regulations, and correspondence between the Party and state institutions in the ESSR concerning the border regimen, form the source base for this research. The Soviet Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD), the Soviet Committee for State Security (KGB), and Militia Administration[2] reports were consulted.

The main obstruction to the thorough research of this topic is the scarcity of KGB and border guard forces documents in Estonian archives. ESSR KGB 2nd Department reports from 1954–58 have indeed survived, but only a few isolated KGB instructions and some related correspondence from later periods remain in Estonian archives. As the KGB’s counterintelligence department, the 2nd Department operated actively in the border zone as well, with the aim of preventing “anti-‐Soviet elements from leaving the territory of the ESSR with impunity”.[3]

Documents generated through the action of the border guard forces, however, are practically nonexistent in Estonian archives. People’s recollections have been used to try to fill in the gaps. To this date, only one collection of memories, an overview in the context of popular current affairs and a brief treatment on the topic of the border zone, have been published about the border regimen in Estonia.[4]

Creation of the Border Regimen and its Initial Implementation in the Estonian SSR in 1940

Universal restrictions on movement were not set for Soviet citizens during the first years of Bolshevik rule. This was also declared by a special decree on 24 January, 1922, which granted all citizens of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic the right to move about freely throughout the territory of the country. The first restrictions were nevertheless established the following year, when legislation was enacted permitting entry to border checkpoints only for occupational business trips with the permission of the provincial executive committee.[5]

The regulations for the defence of the state border, enacted in 1927, started more seriously restricting residence and movement in the near vicinity of the border. Additionally, the concept of the “border belt” (пограничная полоса) was adopted “for the purpose of defending the state border”.[6]

When the establishment of a uniform passport system began in the Soviet Union in 1933, a 100-kilometer-wide belt along the western border of the Soviet Union was designated, within which all residents were required to have passports. This meant that it was forbidden to live there, or to enter it without a passport.[7]

The passport regulations of 1940 extended this requirement to cover the entire state border. Since most Soviet citizens did not have passports until the early 1980s, entering the border belt had become a privilege of the few. The regulation of 1935 entitled Concerning entry to and residence within the border belt amended the corresponding clause in the regulations of 1927: restrictions were reformulated with the aim of establishing “stricter control”, and violations of restrictions were designated as crimes.[8]

These acts of legislation from 1927 and 1935 remained the fundamental documents on which the border regimen was founded until 1960, and the border regimen was established in areas annexed by the Soviet Union on the basis of these same documents, including Estonia.

The prevention of citizens from leaving the country began in Estonia immediately after the occupation of Estonia. First of all, all travel passports of the Republic of Estonia were declared invalid in July of 1940, and Estonian diplomatic passports were also invalidated immediately thereafter.[9]

At the same time, border guard forces of the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD) established control over the Estonian coast and the liquidation of the Estonian border guard began.[10] As early as August, Soviet border guards caught people trying to escape from Estonia by boat, and by October at the latest, the border guards started blocking fishermen from access to the sea.

The establishment of the border regimen according to the Union-‐wide regulation of 1935 began in September. The first local act of legislation that referred to the border regimen was the regulation issued on 26 September 1940 by the ESSR NKVD Militia Administration that prohibited entry to “restricted and border areas” without a permit.[11]

Since the Militia Administration did not have the right to issue universally applicable legal acts, and the circumstances and consequences related to the issuing of the aforementioned regulation are unclear, it is more correct to consider the official birthday of the border zone to be the ESSR Council of People’s Commissars (CPC) decision formulated on 29 November, and implemented on 12 December, which was drawn up at Border Guard Forces headquarters in coordination with the Baltic Fleet.

This decision concerned the “border security regimen” along the coast of the Gulf of Finland and navigation and fishing in the territorial waters of the ESSR, as well as listed areas to which entry was restricted. All of Estonia’s islands were designated as “prohibited zones”, along with certain coastal areas west of Tallinn that were directly at the disposal of the Soviet Navy or within its sphere of interest. Citizens needed a permit from the militia to enter the zone, and visitors had to register within 24 hours after entry. Additionally, there was a more secret zone within the prohibited zone that included the larger islands in the Gulf of Finland, which was completely sealed off to civilians.[12]

Evolution of the Border Regimen during the First Post-war Years, 1944–47

The de facto restoration of the border regimen began immediately after the reoccupation of Estonia in the autumn of 1944 at the initiative of the Soviet Army. Trenches were dug along the northern and western coasts of Estonia, machine gun emplacements were set up, and the entire strip of land along the coast was designated as a border zone. In November, however, a plan was implemented for clearing a 2-kilometer-wide coastal belt of its permanent population throughout the extent of the entire coast.

The operation began with an army directive and culminated in an ESSR CPC regulation that required the authorities in the counties along the coast to resettle residents by 1 January, 1945. Generally, those who were evicted were not offered replacement lodgings, and had to find a new place to live on their own.[13]

It was, of course, impossible to carry this out swiftly. By mid-‐February of 1945, only 227 of the 538 families required had been resettled on the mainland. The order had been carried out to the extent of 30–50% in Hiiumaa, and in Saaremaa, it was completely carried out only on the Sõrve Peninsula. This peninsula had been deserted since 1944 anyway, as the German occupiers had evacuated the local populace away from the fighting.[14]

This ambitious plan had nevertheless been abandoned when the war in Europe came to an end, and for the most part, the people that had been driven out could start going back home, even though the army had in many localities destroyed, removed or laid waste to their houses in the meantime.[15]

New framework documents were drawn up for the border regimen in the autumn of 1946. There had previously not been any need for this, since the ESSR CPC decision of 1940 remained in effect, and no changes had been made in the meantime to Union-‐wide regulations. Furthermore, martial law remained in effect in Estonia until 4 July, 1946, and this in itself restricted freedom of movement.

The USSR Council of Ministers issued a new framework regulation for the border regimen on 29 June, 1946, though that was to be implemented at the Union republic level. An Estonian Communist Party Central Committee (hereinafter referred to as ECP CC) and ESSR Council of Ministers joint regulation was first issued on 28 September, 1946, to establish the new situation, establishing a passport system in the prohibited areas along the coastal border.16 Passports had been issued to about 60 000 people in those areas by the beginning of 1947.

Individuals who were forbidden to live in the border zone (first and foremost persons with criminal records, including persons penalised for so-called ‘political crimes’) according to the passport regulations also had to be identified and expelled from the border belt in the course of this campaign.[17]

The ESSR Council of Ministers regulation Concerning the Estonian SSR’s closed off coastal border belt and its regimen was formulated on 26 October, 1946, replacing the former framework document from 1940. The primary change was that, henceforth, the border belt was defined according to administrative units, including the territories of northern and north-‐western Estonian seaside village soviets and all “islands in the Baltic Sea belonging to the Soviet Union”.[18]

Since the regulation was secret, but certain clauses of it had to be disclosed to the population, it was summarised partially in universally compulsory decisions issued by county executive committees published in the press. This was accompanied by supplementary bans and obligations of a local nature, such as a ban on building campfires on the coast at night or the obligation to black out any windows facing the sea of houses on the seashore.[19]

The shaping of the border regimen culminated in the spring of 1947 with the thorough decision prepared in the ECP CC apparat to make the border regimen “stricter”. The aim of this decision was to more effectively control what was happening in the border belt. Making life in those areas better was supposed to help achieve this goal. Among other things, the entire border belt was to be provided with the best possible personnel at the expense of other areas. All personnel were to be carefully vetted, and unsuitable persons were to be replaced.

The MVD and the Ministry of State Security (MGB) were given their assignment: to remove the “anti-Soviet element” from the border belt. New movie theatres, community centres, and libraries were to be built in the border belt, and all “hostile literature” was to be removed from the libraries. Communications and infrastructure received a great deal of attention. For instance, roads and bridges were to be repaired, all village soviets were to be provided with telephones, bus services were to be improved, and ferry services were to be provided to the islands.[20] The reorganisation of farmland, establishment of sovkhozes (state collective farms) and development of hamlets were priorities in the border belt. This indicates that the set objective was to eliminate low density settlements, which were difficult to control, and to concentrate the population in settlements.

If all these tasks had been completed, life in the border belt would indeed have become better than elsewhere. But that, of course, is not how things turned out. Personnel was actively purged: by the beginning of July, about 70 school teachers had either been sacked or transferred inland, Party organisers and other officials in rural municipalities had been dismissed, and destruction battalions were purged.[21]

The accomplishment of the more major tasks was a great deal more toilsome. Not much had been done yet by the end of the year to comply with the regulation, and only in terms of the repair of roads and bridges was the situation considered satisfactory. The designation of the island of Hiiumaa, which until then had been part of Lääne County, as a separate county in 1946 was also a direct consequence of this regulation. The public was assured that this was the “wish of the working class” as justification for the move. Yet, the justification given in restricted access documents was the need to increase the control exercised by the central authorities over what took place on the island.[22]

Even though the “political and economic strengthening” of the border zone did not proceed at the pace desired, the period of 1946 to 1947 could be considered the decisive period in the development of the border regimen. The construction of border guard stations and communications networks, as well as regular patrolling in the border belt, began in 1946. The guarding of the border was left completely to the border guard forces, since prior to that time, regular army units guarded part of it.

The regulation issued in December of 1946 by the ESSR Council of Ministers established the placement of a large number of facilities at the disposal of the Border Guard. One list placed 45 buildings in Tallinn, Harjumaa and on the Western Estonian islands at the disposal of the Border Guard Forces Administration. Another list “rented long term free of charge” a total of 395 buildings to them in Tallinn, Pärnu and seaside counties. A third list registered 109 residential buildings and apartments in Tallinn, Pärnu, Rakvere, Kuressaare, Kärdla and Haapsalu as housing stock for the Border Guard Forces Administration.[23]

The development of technical capabilities and of the border guard system made escape from Estonia by sea significantly more difficult than it was before. The principles written into the framework regulations during those years, however, remained in effect until the end of the 1980s, even though new legislation continued to be enacted one after another. It is these that we will consider below.

Chronology of Fundamental Documents Related to the Border Regimen

In 1946-‐1987, 14 framework regulations and a number of their amendments and supplements were formulated at the level of the government of the ESSR for regulating the border regimen (see Table 1). The reasons for drawing up new framework documents can be divided into three, often inter-related categories. Firstly, the establishment of new Union-‐wide legislation that the local regulation had to formally be brought into line with. Secondly, changes in administrative division and the structure of official positions, since administrative units in the border zone had to be enumerated in the regulation, as did the officials allowed into the border zone without a permit. Substantive need can be pointed out as the third reason, when the KGB or Border Guard Forces Headquarters had recognised that control has to be made more effective.

The framework regulation issued in 1955 by the ESSR Council of Ministers was conditioned by a new Union-‐wide legal act from 2 years earlier. This also provided the opportunity to describe the extent of the border belt once again, taking into account the consequences of the administrative reform of 1950 in which rajons[24] were formed in place of counties and rural municipalities. The regulations of 1957 and 1959 contained few changes compared to previous regulations. These amendments primarily updated the lists of officials allowed into the border belt without a passport and of administrative units in the border belt.

A new Union-‐wide border guard statute went into effect in 1960, replacing the border guard regulations of 1927 and the border belt regulation of 1935. It was implemented together with the regulation issued on 5 August 1960 by the USSR Council of Ministers.[25]

On this basis, a regulation Concerning the border zone regimen within the borders of the ESSR was issued in 1961. Compared to earlier legal acts, this was a completely new text with many changes. The term “border zone” (пограничная зона) was adopted as a new concept. It was demarcated in the territory of in all rajons, cities, villages or hamlets adjoining the entire state border of the USSR. Until then, the term “border belt” (пограничная полоса) had been in use in the same meaning, but now it was given a new meaning. The border belt was now designated as a narrower area within the border zone. Its width was not permitted to exceed 2 km, and additional restrictions were prescribed in this area compared to the border zone regimen. For instance, while as a rule a permit issued by the militia was required for entry to the border zone, entry to the border belt and residence was allowed only with a permit from the border guard forces.[26]

Table 1. Chronology of ESSR Border Regimen Fundamental Documents 1940–1987[27]

|

|

Fundamental document |

Date |

Union-wide guiding document |

Changes to the fundamental document |

|

1 |

ESSR CPC decision 34 |

29 November 1940 |

USSR Central Executive Committee and CPC 17 July 1935 |

r 172 (6 October 1944); r 188 (13 October 1944) |

|

2 |

ESSR Council of Ministers r 058 |

26 October 1946 |

USSR Council of Ministers r 1435-‐63cc, 29 June 1946 |

r 019 (11 April 1949); r 032 (8 May 1950) |

|

3 |

ESSR Council of Ministers r 07 |

14 February 1955 |

USSR Council of Ministers r2666-‐1124c, 21 October 1953 |

o 05 (1 April 1955); o 196-‐кc (20 February 1957) |

|

4 |

ESSR Council of Ministers r 385-‐22c |

30 November 1957 |

"" |

– |

|

5 |

ESSR Council of Ministers r 160-‐14c |

30 April 1959 |

"" |

o 1249-‐рсс (5 September 1960) |

|

6 |

ESSR Council of Ministers r 91-‐10 |

1 March 1961 |

USSR Council of Ministers r 847-‐349, 5 August 1960 |

r 302-‐23 (12 June 1963); r 384-‐23 (17 August 1964) |

|

7 |

ESSR Council of Ministers r 255-‐12 |

1 June 1966 |

"" |

– |

|

8 |

ESSR Council of Ministers r 216-‐13 |

24 May 1967 |

"" |

r 361-‐30 (4 August 1970); r 169-‐18 (17 April 1972) |

|

9 |

ESSR Council of Ministers r 223* |

29 May 1967 |

Union-‐wide directive |

r 7 (10 January 1968) |

|

10 |

ESSR Council of Ministers r 236* |

21 May 1969 |

Union-‐wide directive |

r 294 (16 June 1970) |

|

11 |

ESSR Council of Ministers r 296-‐14 |

21 June 1973 |

USSR Council of Ministers r 847-‐349, 5 August 1960 |

r 389-‐28 (25 July 1977) |

|

12 |

ESSR Council of Ministers r 297* |

21 June 1973 |

Union-‐wide directive |

– |

|

13 |

ESSR Council of Ministers r 348* |

29 July 1976 |

Union-‐wide directive |

r 578 (28 November 1977); r 201 (18 April 1979); r 202 (18 April 1984) |

|

14 |

ESSR Council of Ministers r 453-‐33 |

28 July 1983 |

USSR Council of Ministers r163-‐88, 17 February 1983 |

|

|

15 |

ESSR Council of Ministers r 654** |

25 December1987 |

– |

|

The 1966 regulation once again changed mainly the list of officials allowed in the zone without permits, since a couple of Union-‐wide directives on this topic had been sent out in the meantime. A proposal submitted by the border guards to start drawing up two separate regulations for regulating the border regimen led to the implementation of the subsequent regulation in 1967 less than a year after the previous regulation. One of those two regulations, Concerning the border zone regimen within the borders of the ESSR, was secret, as usual. But the other, Concerning the procedure for entering the border zone within the borders of the ESSR, was subject to restricted access.

The latter was considered necessary to produce a document that would provide guidance at ticket counters, bus depots, airports, local executive committees, factories and elsewhere. Henceforth, a list of railway stations, airports and ports located within the border zone (but not an enumeration of administrative units belonging to the border zone) was included in the unclassified regulation, along with the organisation of civilian transportation, the list of officials allowed into the zone without permits, a list of resorts, and instructions for business travelers, sanatoriums, children’s summer camps, and other such information that affected a large proportion of the population.[28] The restricted access regulation was implemented on 29 May, 1967, and its subsequent drafts in 1969, 1973, and 1976.

The secret regulation Concerning the border zone and its regimen in the territory of the ESSR issued in 1973 originated from Border Guard Forces Headquarters, from where it was sent to the Party Central Committee, the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the KGB for approval. According to the border guards, a new framework document was needed, since the number of watercrafts at the disposal of citizens had grown quickly in recent years, and there were too few moorings that were guarded according to requirements, especially “along the unguarded seacoast”. This was seen as the primary reason why many escape attempts from the Soviet Union had been made in recent years using privately owned or stolen vessels. The border guards demanded stricter control to prevent further escape attempts, and the regulation established some new restrictions.[29]

The act governing the state border of the Soviet Union went into effect on 1 March, 1983, annulling the Union-‐wide border guard statute from 1960. The USSR Council of Ministers issued its own regulation on 17 February, 1983, to implement that act, and on that basis a new ESSR Council of Ministers regulation was drawn up on 28 July, 1983, as the new local framework document. There were few changes compared to the former procedures, and the new legal act was characterised more by greater precision and detail than before. The concepts of the border zone and the border belt remained, but the former 2-‐kilometer maximum limit for the border belt was done away with. The rules for entry also remained the same, but the rights of the border guard forces to control the border regimen increased.[30] It can be said that this regulation made the border regimen even stricter.

Regulation of the Border Regimen

The rules for living in border areas, and for entry into those areas, changed little over time. For instance, if we compare the border belt regulation of 1935 to the instructions from 1983, they are almost identical in matters concerning entry into border areas or living in those areas. The text had simply become more detailed over the course of nearly half a century.

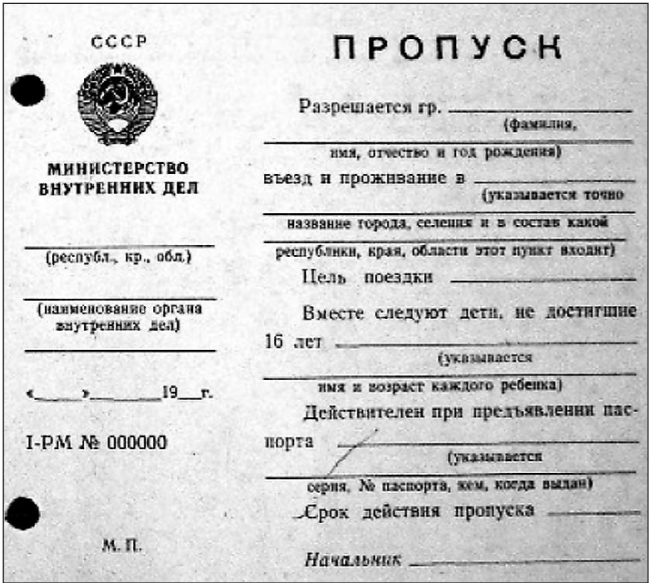

The basic procedure was very simple: a passport containing address registration for some location situated within the border zone or border belt was required to live in areas along the border, and the passport had to contain the requisite stamp. Local residents had to always have their passports with them when moving about in the zone. People who lived elsewhere had to apply for a permit from their local militia station, and to supply documentation to prove the necessity of their trip in order to enter the border zone. Institutions located within the border belt or in the border zone were not permitted to hire people who did not have the required permit. Similarly, local residents were not permitted to take in people without the required permit as boarders.

New qualifying clauses were constantly being added when new regulations were drawn up. The list of activities that were forbidden in the zone, or that required a permit, grew ever longer. Rigid restrictions were set for everything concerning maritime marine navigation, while hunting, holding sporting events, and so on, were regulated. In 1955, it was considered necessary to add a separate clause prohibiting topo-‐geodetic work, photographing and filming in the zone without a permit. Among other things, keeping pigeons was also prohibited.

A clause was added in 1959 concerning pupils and students registered as residents in the border belt who attended school elsewhere, somewhat simplifying the procedure for their return trips home. It granted them the right to pass through the checkpoint with their student card and the corresponding certificate from their local village soviet.

Some notable changes were made in 1961. The regulation added that citizens with passports containing the border zone stamp ("ЗП") were permitted to travel in the border zone within the Estonian SSR, since previously the permit was apparently valid throughout the Soviet Union. Recognition that a permit valid throughout the USSR somewhat simplifies escape from that state was most likely behind this change.[31]

At the same time, a clause was added to the framework regulation that had been missing from it since 1946 that required registration within 24 hours after entry into the border zone. This does not mean that the aforementioned requirement did not apply in the meantime. Namely, the passport regulations of 1940 established a universal requirement for registration within 24 hours of arrival in any location whatsoever. This clause was eased somewhat later on, extending the deadline for address registration, but the border belt regulation of 1961 meant that the 24 hour requirement remained in effect in the border zone, and applied more or less until the end of the Soviet era.

The application procedure for permits was elaborated on in the 1970s, and the cases that were prerequisites for obtaining permits were described in detail. As a rule, one-‐time permits were issued singly to individuals for a specific settlement. Permits valid for several locations or for an entire rajon altogether were issued in exceptional cases, for instance to persons engaged in certain occupations who had to travel about a great deal due to the nature of their occupation.

Permits that could be used repeatedly for up to one year could be issued for visiting relatives living in the border zone. Citizens who resided temporarily in the border zone could be issued with a permit for up to 45 days, later for up to three months and then for up to six months.

The MVD, KGB and other institutions issued an immense number of directives and instructions for the implementation of these regulations. Unfortunately, however, most of them are not accessible, because the archives of these institutions were removed from Estonia when the Soviet Union collapsed, and access to them is not available in Russian archives. Instructions from 1983 are preserved in the archives.

They provide more detailed information concerning the procedures in effect at that time, as well as matters such as the issuing of permits and the preceding procedure for special checks, factors hindering the acquisition of permits, and other such items.[32] The procedure that was previously in effect was also most likely about the same. This allows us to assume the equivalence of legal acts from different periods in terms of other details.

As a rule, border zone permits were not to be issued to citizens of foreign countries and stateless persons. The state security units and those for internal affairs had the right to prohibit entry to the border zone for persons whose presence there was undesirable due to “operational considerations”. There were special rules for persons with criminal records.

The local unit for internal affairs was responsible for issuing all manner of residency permits to persons released from penal institutions within its territorial jurisdiction, including the right to enter the border zone. The unit for internal affairs was responsible for checking the right of the incarcerated person to enter the border zone, that is to say, whether the person being released had lived there previously or if his immediate relatives had formerly lived there. The unit for internal affairs at the destination was responsible for providing its evaluation, and had the power to ban the released person from taking up residence in the border zone.

Certain sentences brought with them restrictions on address registration that made settling in the border zone significantly more difficult until the end of the Soviet era. In the context of Soviet repressive policy, this restriction actually meant that many people were prohibited from returning to their homes. The system that was in effect since 1940 enumerated counterrevolutionary and criminal acts, hooliganism (until 1952) and not engaging in socially useful work as the basis for restrictions.

From 1974 onward, address registration restrictions applied to particularly dangerous repeat offenders and persons who had been sentenced to imprisonment or exile for particularly dangerous crimes against the state (10 sections were in turn categorised as such crimes, including anti-‐Soviet agitation and propaganda, betrayal of the homeland, and others). The list included a number of serious criminal assaults and economic crimes, as well as “dissemination of fabrications that are known to be false denigrating the system of government or the social system”. It was nevertheless possible to make exceptions in this regard, and exceptions were indeed applied.

Not only persons with criminal records but also more or less everyone who applied for a border zone permit was subjected to special control. Citizens had to submit a written petition and documents substantiating the aim of the trip (documentation concerning the residence of relatives in the zone, job offer from an institution, or other such documentation) 10 days before their planned trip at the latest in order to obtain a permit.

This was followed by special control, the thoroughness of which depended on where the applicant lived: stricter control was required in the case of people living in the administrative centre of a union republic (ASSR, oblast, kraj). Address bureaus and the 10th department of the corresponding security unit carried out the check.33 The security unit was required to provide its answer within 2–3 days if the purpose of the trip was not a funeral or to visit someone who was seriously ill. In such cases, the instructions required that the check be carried out “immediately”. The organs were not required to disclose their motives in cases where permission was denied.[34]

Source: Käsmu Maritime Museum

Extent of the Border Belt and Border Zone

In 1940, all islands in Estonia’s coastal waters and certain areas of Estonia’s northern coast were included in the “prohibited zone”. As of 1946, “all islands in the Baltic Sea belonging to the Soviet Union” and 36 village soviets along Estonia’s northern and north-‐western coast were defined as belonging to the border belt. In subsequent years, changes were made in the description of the restricted area, most of which were due to reorganisation of administrative units. The number of village soviets, for instance, decreased by more than a factor of three over the course of 40 years.[35]

The regulation issued in 1955 took into account the consequences of the major administrative reform of 1950, in the course of which rajons were formed in place of counties and rural municipalities. Henceforth a total of 24 village soviets in seven rajons stretching from Narva-Jõesuu to Matsalu Bay on the Estonian mainland were part of the border belt.

By 1983, their number gradually decreased to 19. This, of course, did not mean a narrowing of the border zone but rather the opposite, because the amalgamation of small village soviets increased the size of the area covered by those village soviets. At the same time, all these changes were formal, adhering to the principle that every administrative unit adjacent to the sea is part of the border zone. The situation was exactly the same elsewhere in the Soviet Union as well: for instance, in Latvia, 13 village soviets and some hamlets in its three rajons located on the western coast were part of the border zone in 1983, and in Lithuania, 9 village soviets and the Nida Peninsula in its four seaside rajons were in the border zone.

The expansion of the border zone was not large, but it nevertheless painfully affected people with criminal records who were subject to restrictions affecting where they were allowed to live. As the border zone expanded, they had to move repeatedly. This affected areas in the near vicinity of Tallinn in particular, where many people who were banned from living in the city had settled.[36]

It must, however, be noted that it was chiefly moving to village soviets located in the border belt or border zone, meaning address registration, that was restricted. This did not always necessarily mean denial of permission to enter the territory of a particular village soviet or strict control at the border of the village soviet. The necessary checkpoint with its gate was set up within the zone wherever necessary or where it was easiest to set up, and that depended to a great extent on the local border guards.

Cities, as a rule, were not part of the border belt or border zone, but there were always exceptions to this rule. There were two such exceptions in Estonia. First of all, Paldiski, which was essentially sealed off to the civilian population for the entire Soviet era. In 1964, the city and the entire Pakri Peninsula were given special status because “Object 346” belonging to the USSR Ministry of Defence was located there. The area was declared a restricted zone (закрытная зона), where not only the border regimen was in effect, but also its own special regimen in addition.[37]

The other exception was Sillamäe, located in the border belt along the northern coast. Sillamäe officially gained town status in 1957 and in subsequent framework regulations, it had to therefore be singled out separately as a town that was part of the border zone, unlike other towns.[38]

The administrative centres of union republics (like those of ASSR’s, oblasts and krajs as well) were not part of the border belt or border zone, but in 1946, the leadership of the ESSR concocted a plan to include Tallinn in the border belt as well, hoping in this way to ensure better order in the city and to obtain additional means for combating the hordes of illegal immigrants coming from Russia. Baltic Fleet Headquarters also supported the proposal. In its opinion, Tallinn merited a stricter regimen as a border city on the coast and the location of the main base of the fleet, similarly to other naval bases (like Sevastopol or Vladivostok). A draft regulation was prepared by the ECP Central Committee that prescribed Tallinn’s inclusion in the border belt and the expulsion of people caught without residence permits.[39]

Then, however, the plan was shelved, since it most probably went against the fact that making exceptions in a unified system was simply out of the question, and the implementation of the border regimen was not prescribed for the capitals of union republics. At the same time, special rules deriving from the passport regimen were in effect in capitals that, similarly to the border regimen, were meant to control migration and the composition of the population.

Exceptions

The framework regulation of the border regimen was always accompanied by a list of settlements and areas that were exceptions. These were located within the border zone, but entry into them was not restricted. Often, the reason for the addition or removal of a particular settlement from the list was simply a change in administrative jurisdiction, or in the status of the settlement. Beyond that, an official list of summer holiday resorts existed, drawn up by the local executive committee in cooperation with the Border Guard. Citizens of the ESSR, meaning people with a permanently registered address in Estonia, could visit those places during the “summer holiday season”, in other words from 1 May (later from 1 April) until 1 October.

At the same time, visitors always had to bear in mind that they could remain at the seashore only in daylight, in other words from 07:00 until 22:00. This last requirement also applied outside of the border zone as well, for instance at Tallinn’s public beaches. Sanatoriums, children’s summer camps (“pioneer” camps) and other holiday or health institutions formed a separate category of exceptions to which people had access on the basis of corresponding holiday packages or referrals. Finally, there were also exceptions that were valid under certain conditions, or for local residents so that people could go to the market, visit the hospital, go to their summer cottage, or other such activities.

The maritime islands, as a rule, were part of the border zone throughout the Soviet era, and visiting them without a permit was utterly impossible for ordinary citizens living elsewhere until 1961. This applies particularly to the islands in the Gulf of Finland, from which their permanent population was forcibly resettled to the mainland by the beginning of the 1950s (except for Prangli Island). The first exception in a long time emerged in the system in 1961, since Aegna Island, located near Tallinn, was declared an area for summer holidaying.[40]

While initially all ESSR citizens theoretically had the opportunity to visit that island on their own in the summer, only people whose address was permanently registered in the Tallinn and Harju rajon retained that right in 1973–83 (that was one of the proposals made by the border guard forces for making control of the border regimen more effective). Foreigners were allowed onto the island only via a holiday package to a holiday resort, or as part of a tour group.

One further significant change was made in 1966 when Kihnu Island, located in the Gulf of Riga, was counted out of the border zone.[41] In practice, people were not prevented from visiting the islets in the Väinameri Straits between the Estonian mainland and the Western Estonian archipelago, where a number of organisations and enterprises had their holiday resorts.

In addition to exceptions, temporary anomalies arose. For instance, in 1953 after Stalin’s death, Lavrenti Beria initiated the liberalisation of the system, as a part of which a certain relaxation of the passport system was also planned and an amnesty was declared.[42]

A number of restrictions on place of residence were done away with, including within the area extending to 100 km along the border of the Soviet Union. According to Beria, this kind of system, which was not in use anywhere else in the world, was useless from the standpoint of guarding the border and hindered economic development.[43]

The brakes were pulled on Beria’s attempt at liberalisation, however, immediately after he was removed from power, and in that same autumn, a new passport regulation was approved that restored all the former restrictions. The effect of Beria’s liberalisation attempt and amnesty, however, is expressed in Estonia in the statistics of entry permits issued for the border belt, because the number of permits increased many times over for a short period of time (see Table 2).

We find another interesting deviation in 1956, when the Party leader in the ESSR, Ivan Käbin, and the leader of the government, Aleksei Müürisepp, submitted a proposal to the USSR Minister of Internal Affairs to exclude the village soviets in the near vicinity of Tallinn from the border belt. The wish to offer city residents opportunities for summer vacationing was put forward as justification for the proposal.

A USSR-‐wide campaign for improving the living conditions of the population in general supported the plan. Within the framework of this campaign, a USSR Council of Ministers regulation prescribed the construction of 300 summer cottages and their sale to Tallinners. Furthermore, children’s summer camps (pioneer camps) and vacation resorts were located in those village soviets.[44]

The matter culminated in February of 1957 with an order from the ESSR Council of Ministers that excluded 4 village soviets in the near vicinity of the city from the border belt. This joy was, nevertheless, short-‐lived for city residents, because the new border regimen framework regulation, issued that very same autumn, returned them to the border belt.[45]

It is possible that the ESSR leadership had acted without approval from Moscow and with undue haste, but it is more likely that the border guard forces or the KGB realised that the narrowing of the border zone had gone too far. In that case, the escape of Eugen Adrik to Sweden by sailboat in August of 1957 (considered further below) could have had decisive impact.

Privileges of the Nomenklatura[46]

A list of positions that made it possible to enter the border zone without a permit formed one group of exceptions. The inclusion of such lists with framework regulations began as early as 1946. These lists were based on USSR-‐wide lists that were usually established as a joint directive issued by the heads of several institutions, one of which was always the Minister of Internal Affairs or the chairman of the KGB.[47]

These lists, which for the most part coincided with the enumeration of nomenklatura positions, were divided up into several levels, similarly to the nomenklatura. Positions that ensured “unlimited” entry[48] throughout the entire extent of the Soviet Union’s state border formed the first level. The lists of this level were so secret that they were not included with the ESSR regulations. Instead, this document only referred to some USSR-‐wide document. The next level consisted of persons who did not require a permit issued by the militia; their identity document was sufficient to allow entry.[49] The third level consisted of persons who required a business trip certificate in addition to their passport.

The fourth level consisted of persons to whom the militia issued long-‐term permits (that is, for six months or a year). Ordinary citizens could also apply for this kind of long-‐term permit under certain conditions. The positions of the lower-‐level lists were in turn divided into lists where the right of entry was valid throughout the Soviet Union, only in their own Union republic (ASSR, oblast or kraj), or only within the boundaries of their own rajon respectively.

In summary, the system was so complex that lists that were often updated ultimately consisted of dozens of pages and hundreds of official titles. This, of course, is not because the border regimen had become more lenient, but rather because the list of official nomenklatura positions became ever longer.

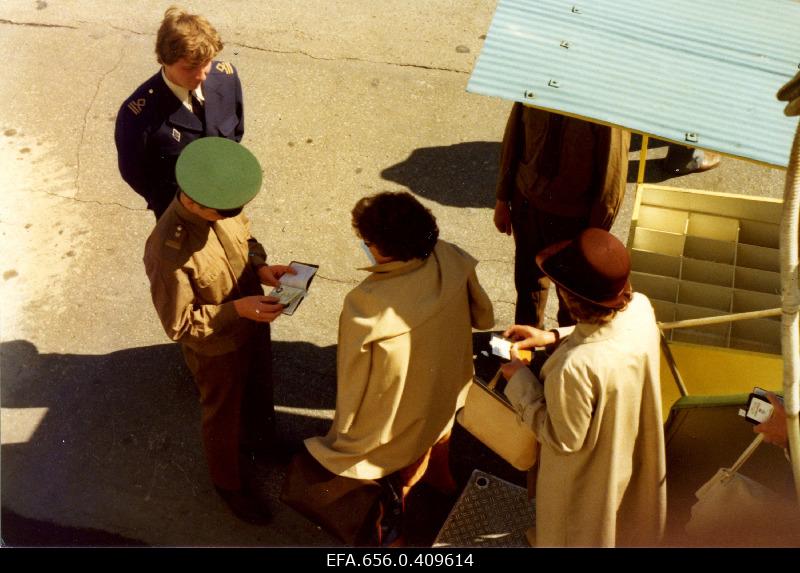

There were also special rules for organising transportation in the border zone. The framework regulation established the list of highways and railways passing through the border zone along with the railway stations, harbours and airports located in the zone. These kinds of railway stations could be passed through but people were not allowed to disembark. When purchasing a ticket to any of these listed stations, the purchaser had to produce a permit indicating the station of destination.

A similar system applied to bus lines. Driving on highways passing through the border zone was open to all automobile drivers, but road users without border zone permits were not permitted to get out of their automobile or to stop anywhere within the zone for any reason other than a traffic accident.

The rules for marine navigation, as a very important domain from the viewpoint of the border regimen, became stricter and ever more detailed over time. It was stipulated as early as 1940 that all fishing, sporting and pleasure boats sailing in the Gulf of Finland had to be registered with local governmental organisations regardless of the size, capacity and power of the watercraft.

The number and certificate obtained from the local governmental organisation had to, in turn, be immediately registered with the local border guard detachment corresponding to the owner’s place of residence. Watercraft could only be kept in places determined by the border guard. Landing and loading were prohibited anywhere else. All watercraft moored at ports had to be locked and guarded.

All watercraft were permitted to sail at any time within 12 nautical miles of the coastline for the purpose of fishing, economic activity or scientific work, but pleasure boats and sporting craft were permitted to sail only during the daytime, and only within 3 nautical miles of the coast. Putting out to sea and landing was permitted only in the presence of border guards. From 1946 onward, all watercraft had to be registered at a specific fixed port or landing place. Boats had to be locked and oars, oarlocks and sails had to be stored separately. This requirement was extended to include outboard motors in 1967.

Fishing permits started being issued for one season at a time in 1946, and amateur fishermen were forbidden to catch fish at night. The life of professional fishermen was made a little easier in 1955 when they were permitted to land at all corresponding landing places to unload their catch regardless of where their craft was registered. As an exception, fishermen were not allowed to unload their catch in Paldiski Bay, where fishing boats and other civilian craft had no business being in the first place. The same restriction was placed on the port of Mõntu in Saaremaa in 1973.

The focus was aimed at yachtsmen in 1957. The reason was the escape by Eugen Adrik and his two companions on a sporting association yacht to Sweden upon having received permission to sail from Tallinn to Klaipeda in Lithuania. The case was sensitive due to the circumstance that the yacht’s captain Adrik, a USSR champion sportsman in yachting, was a Red Army Estonian Rifle Corps veteran and also a former agent of the security units.[50]

The ESSR Supreme Court sentenced the fugitives by default to 10 years imprisonment. The case reached the ECP Central Committee, and the head of the ESSR KGB 4th Department Leonid Burdin was reprimanded, while his first deputy Gavriil Starinov was given a warning, after which measures quickly began to be taken. Yachts were henceforth prohibited from sailing beyond territorial waters, and special control was established over yachtsmen and sailing on the open seas at night.[51]

The 1960s brought new provisions that primarily affected fishing boats, which the border guard justified on account of previous escapes abroad of boats or members of boat crews. First of all, a narrow entry gate was established and designated in the Irben Straits in 1960 for ships departing from and arriving at Riga. The following year, seagoing vessels were forbidden to go fishing alone.

At least two seagoing vessels had to be together in order to be allowed to put out to sea (larger ships were relieved of this restriction in 1966 under the condition that they were in radio contact with the shore). Minimum requirements were also set for the number of crew members; trawlers had to have at least five, while boats had to have at least two people in order to put out to sea. Four hours before departure at the latest, the border guard had to be informed where the craft was going and when it would be returning. The maximum permissible distance from the coast was reduced to 2 miles for amateur fishermen.

The next significant change came in 1967, when the entire set of rules affecting watercraft and fishing was extended to those areas of the Gulf of Riga and the Väinameri (the body of water between continental Estonia and Estonia’s western islands) that the Border Guard did not keep under surveillance. Essentially, this established some rules of the border regimen in areas that were not even in the border zone. The specific term “coastline without surveillance” was also adopted, concerning which new restrictions were implemented thereafter (primarily according to proposals made by the border guard forces). A new rule that applied throughout the entire coastline was established in 1967, requiring that the power of boat motors in private possession may not exceed 20 horsepower.

The Issuing of Permits

While the border guards shouldered the greater burden in controlling the border regimen and the role of the militia was smaller, the militia units did most of the work in issuing permits for entry into border areas. Restricted access militia statistics from 1945 and 1952-‐1987 concerning issuing of permits have been preserved (see Table 2).

The ESSR NKVD Militia Administration issued over 39 000 such permits in 1945.52 The number of permits steadily increased later. This was partially due to a certain expansion of the border zone and an increase in the population, but more generally we can also see the attitudes of the regime here which became somewhat more conciliatory over time in terms of allowing people to the seashore.

Table 2. Issuing of Border Zone Permits by ESSR Militia Units 1952–1987 (thousands)[53]

|

1952 |

17 |

1958 |

39 |

1964 |

43 |

1970 |

82 |

1976 |

95 |

1982 |

92 |

|

1953 |

16 |

1959 |

33 |

1965 |

44 |

1971 |

90 |

1977 |

88 |

1983 |

118 |

|

1954 |

80 |

1960 |

31 |

1966 |

47 |

1972 |

99 |

1978 |

88 |

1984 |

134 |

|

1955 |

25 |

1961 |

36 |

1967 |

51 |

1973 |

103 |

1979 |

90 |

1985 |

148 |

|

1956 |

31 |

1962 |

42 |

1968 |

61 |

1974 |

110 |

1980 |

100 |

1986 |

167 |

|

1957 |

37 |

1963 |

38 |

1969 |

74 |

1975 |

110 |

1981 |

118 |

1987 |

94* |

The year 1954 was exceptional with over 80 000 permits, reflecting the relaxation of restrictions on place of residence due to the so-called Beria amnesty. The effect of the 22nd Olympic Games Tallinn Sailing Regatta can be assumed in the case of the decrease that took place in 1976-‐1980, prior to and during which restrictions on movement and place of residence were made stricter, “unsuitable elements” were expelled from Tallinn, and other such actions.

The sharp increase that took place in 1984 is explained by the new MVD border regimen regulations that simplified application for border zone permits. Some reports make it possible to estimate that the number of permits issued to people living permanently in the border zone formed about a fifth of the total number of permits.[54]

Indrek Paavle (1970-2015) was an Estonian historian. He completed his PhD in 2009 at the University of Tartu, and held the position of Senior Researcher at the Estonian Institute of Memory Foundation. His primary research interest was the history of Estonia in the twentieth century, in particular the history of the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic.

List of Sources

1 Robert Service. Seltsimehed : maailma kommunismi ajalugu (Comrades! : A History of World Communism). Varrak, Tallinn, 2010, pp. 422–436.

2 Miliciya or militia (Russian: мили́ция) is used as an official name of the civilian police in several former communist states. The Main Administration of the Militia was formed in 1932 as a new union-‐wide central institution at the same time as the passport system was established. This was justified by the need to directly supervise the work of the militia administrations in the union republics in implementing the passport system. The ESSR Militia Administration was established in the autumn of 1940.

3 Report on the work of the State Security Committee 2nd Counterintelligence Department for the period of 1 April 1954

– 1 April 1955 to the ESSR Council of Ministers. Rahvusarhiiv (Estonian National Archives), Tallinn, 1997, p. 99.

4 Nõukogude piir ja lukus elu : meie mälestused (The Soviet Border and Life Locked-‐up: Our Memories). Compiled by Enno Tammer. Tammerraamat, Tallinn, 2008; Virkko Lepassalu. Riigipiir (The State Border). Pegasus, Tallinn, 2010; Restricted Access Border Zones of the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic. – Kalev Sepp (ed). The Estonian Green Belt. The Estonian University of Life Sciences, Tallinn, 2011, pp. 12–16.

5 Decree issued by the Russia-‐wide Central Executive Committee, 28 March 1923. – http://www.dekrets.ru/doc.php?docid=03733 [viewed on 23 February 2012].

6 Regulation issued by the USSR Council of People’s Commissars (hereinafter referred to as CPC) and the Central Executive Committee, 15 June 1927. – Справочник по законодательству для судебно-‐прокурорских работников (Legislation guide for court and prosecutor’s office employees), Part I. Moscow, 1949, pp. 278–282.

7 Indrek Paavle. Ebaühtlane ühtne süsteem : sovetliku passisüsteemi kujunemine, regulatsioon ja rakendamine Eesti NSV-‐s (A Non-‐uniform Uniform System: the Evolution, Regulation and Application of the Soviet Internal Passport System in the Estonian SSR). – Tuna, 2010, nr 4, pp. 37–53. Also available on the internet: I. Paavle. The Evolution, Regulation and Implementation of the Soviet Internal Passport System in the Estonian SSR. – http://www.mnemosyne.ee/publikatsioonidpublications/lang/en-‐us .

8 Regulations governing entry to and temporary stays in border areas and prohibited regions in the USSR, ERA.R-‐ 34.1.9b, pages not numbered.

9 Regulation issued by the Minister of Internal Affairs, 21 July 1940. – Riigi Teataja (RT, National Gazette in English), 1940, 79, 757; Regulation issued by the Minister of Internal Affairs, 29 July 1940. – RT, 1940, 87, 841; Announcement

from the Minister of Foreign Affairs, 30 July 1940. – RT, 1940, 87, 843.

10 Olavi Punga. NSVLi julgeolekuväed Eestis aastail 1940–1941 (USSR Security Forces in Estonia in 1940–1941). – ENDC (Estonian National Defence College) Proceedings no. 11. TÜ Kirjastus (University of Tartu Publishing House), Tartu, 2008, p. 186. See: Tiit Noormets. Fate of the estonian border guard in 1940–1941. – Estonia 1940–1945 : reports of the Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity. Tallinn, 2006, pp. 257–271.

11 ESSR Workers’ and Peasants’ Militia Administration regulation, 26 September 1940, ERA.R-‐34.1.5, pp. 1–3. The wording of the document was taken from an extremely poor translation of the regulation of 1935 containing requirements that were impossible to implement in Estonia due to particular local conditions.

12 ESSR CPC Decision no. 34, 29 November 1940, ERA.R-‐1.5.10, pp. 244–247; Saarte Hääl (Voice of the Islands), 23 December 1940. Most of the content of this decision was also published in local newspapers. Of the 13 clauses of the decision, 2 were secret and their existence was hidden when the regulation was disclosed by changing the numbering of the clauses.

13 ESSR CPC Regulation no. 029, 21 December 1944, ERA.R-‐1.5.90, p. 106. See also: Kaljo-‐Olev Veskimägi. Kuidas valitseti Eesti NSV-‐d (How the Estonian SSR was Governed). Varrak, Tallinn, 2005, pp. 124–125.

14 Letter from the 8th Army War Council to the chairman of the ESSR CPC, 14 February 1945, ERAF.1.3.500, pp. 4–5.

15 Endel Saar. Hiiumaa – kiviajast tänapäevani (Hiiumaa – From the Stone Age to the Present). E. Saar, Kärdla, 2004, pp. 132–138.

16 Regulation issued by the ESSR Council of Ministers and the ECP CC, 28 September 1946, ERAF.1.4.322, pp. 206–207.

17 I. Paavle. Ebaühtlane ühtne süsteem (Non-‐uniform Uniform System). Part II, p. 48.

18 ESSR Council of Ministers Regulation no. 058 Concerning the ESSR’s closed off coastal border zone and its regimen, 26 October 1946, ERA.R-‐1.5.118, pp. 233–239.

19 Saaremaa Workers’ and Soldiers’ Soviet Executive Committee universally compulsory decision no. 5 Concerning the rules for the behaviour of residents in the closed off region adjacent to the border. – Saarte Hääl, 20 May 1947.

20 Shorthand records of the ECP CC session on 19 March 1947, ERAF.1.4.480, 201–204; ESSR Council of Ministers and ECP CC Regulation no. 020, 28 March 1947, ERAF.1.4.419, pp. 12–28.

21 Letter from the ECP Harju County Committee, 30 May 1947, ERAF.1.5.24, pp. 3–4; Kaljo-‐Olev Veskimägi. Nõukogude unelaadne elu : tsensuur Eesti NSV-‐s ja tema peremehed (Dream-‐like Soviet Life: Censorship in the Estonian SSR and its Masters). K.-‐O. Veskimägi, Tallinn, 1996, p. 143. Destruction battalions were formally volunteer armed organisations that helped the security units in the western regions of the Soviet Union to suppress the resistance movement in the 1940’s. See: http://www.estonica.org/en/Destruction_battalions/.

22 Minutes of the ECP CC Bureau, 3 July 1946, ERAF.1.4.308, pp. 20–21.

23 ESSR Council of Ministers Regulation no. 069, 18 December 1946, ERA.R-‐1.5.118, pp. 290–307. A secondary objective of this regulation was to recover buildings occupied by the Border Guard without authorisation, prescribing that facilities not entered on the list “must be vacated immediately and incontrovertibly” and are to be placed at the disposal of local institutions of state authority.

24 Rajon (also raion or rayon) is an administrative unit in the Soviet Union. It is the next administrative level after the oblast, that is to say oblasts were divided up into rajons. The rajon was the first local administrative level in Soviet republics that were not divided up into oblasts.

25 Statute concerning defence of the border of the Soviet Union. – ENSV Ülemnõukogu Teataja (ESSR Supreme Soviet Gazette), 1960, 29, pp. 603–611.

26 ESSR Council of Ministers Regulation no. 91-‐10 Concerning the border zone regimen within the borders of the Estonian SSR, 1 March 1961, ERA.R-‐1.5.557, pp. 27–39.

27 Abbreviations and notations: r – regulation, o – order; legal acts to which access was restricted are indicated with an asterisk (*), all other remaining documents were either secret or top secret except for the very last one, the regulation of 1987 that was already available to the public. – ERA.R-‐1.5.10, pp. 244–247; 90, pp. 26–28; 90, p. 19; 100, p. 124; 118,

pp. 233–239; 185, pp. 113–114; 213, p. 222; 358, pp. 20–26; 360, pp. 6–7; 431, p. 104; 429, pp. 119–127; 492, pp. 42–

51; 528, p. 31; 557, pp. 27–39; 617, pp. 87–91; 647, pp. 140–141; 706, pp. 26–53; 735, pp. 52–70; 802, p. 87; 850, p. 47;

872, pp. 42–55; 974, pp. 63–69; ERA.R-‐1.3.2213, pp. 43–64; 2328, pp. 253–255; 2554, pp. 126–149; 3721, pp. 141–144;

ERAF.17SM.14.102, pp. 1–4, 16–19; 94, pp. 103–111; ENSV Teataja (ESSR State Gazette), 1988, 2, 38.

28 Statement, March 1967, ERA.R-‐1.5.735, pp. 61–63.

29 Letter from the commander of the 106th Border Guard Squad to the chairman of the ESSR Council of Ministers, March 1973, ERA.R-‐1.5.889, pp. 31–31p; ERA.R-‐1.5.872, pp. 53–55.

30 USSR act concerning the state border of the Soviet Union. Official text as of 1 March 1983. Eesti Raamat, Tallinn, 1987. To implement this act, the following regulations were issued: USSR Council of Ministers Regulation no. 163-‐68, 17 February 1983, ERAF.17SM.14.102, pp. 20–22; ESSR Council of Ministers Regulation no. 453-‐33 "О пограничном режиме в пограничной зоне на территории Эстонской ССР" (Concerning the border regimen and border zone in the territory of the Estonian SSR), 28 July 1983, ERAF.17SM.14.102, pp. 16–19.

31 Elsewhere in the Soviet Union, the permit was valid as of 1961 within the territory of autonomous SSR’s (ASSR), oblasts and krajs respectively. This restriction had not been included in regulations previously. It is possible that the situation was elaborated on in instructions that have not been located to this date, but most likely this meant that the permit was valid in the border belt throughout the USSR. People who have escaped to Finland over the border of Karelia have also claimed that this was the case, and that they used this circumstance to aid their escape.

32 USSR MVD Directive no. 0285, 13 October 1983, ERAF.17SM.14.109, pages not numbered.

33 The ESSR KGB 10th Department was subordinate to the USSR KGB 10th Department Main Administration and also issued permits to foreigners for entry into the ESSR and to Soviet citizens for travel abroad. It also drew up the foreign travel files of people travelling abroad. The procedure for both special checks was also quite similar. The address bureaus managed enormous card files containing data concerning the movement of people, that is the transfer of address registration from one place to another.

34 USSR MVD Directive no. 0285, 13 October 1983, ERAF.17SM.14.109, pages not numbered.

35 For further detail, see: Liivi Uuet. Eesti haldusjaotus 20. sajandil : teatmik (Estonia’s Administrative Division: a Reference Book). Eesti Riigiarhiiv, Tallinn, 2002.

36 For instance, Ageeda Paavel was released from prison camp in 1955 but was not allowed to return to live in her former place of residence in Tallinn. She succeeded in obtaining address registration about 25 km outside of the city in the village of Valingu. Her address registration of 1955 was nullified since the border regimen caught up with her, so to speak, due to changes in the boundaries of administrative units. – Interview with Ageeda Paavel, 1 March 2012.

37 ESSR Council of Ministers Regulation no. 384-‐23, 17 August 1964, ERA.R-‐1.5.647, pp. 140–141. The 93rd Naval Training Centre (the so called training centre for nuclear submarine crews) was located in Paldiski. It was established in 1964 and placed in operation four years later, see: Jüri Pärn, Margus Hergauk, Mati Õun. Punalaevastik Eestis 20. sajandi lõpukümnendeil (The Red Fleet in Estonia in the Latter Decades of the 20th Century). Sentinel, Tallinn, 2006, p. 37.

38 The main reason for Sillamäe’s special status was the secret object located there, the uranium enrichment factory Combined Plant no. 7, the construction of which began in 1946.

39 Letter from Karotamm, Tributs and Jefremov to Zhdanov, undated document [filed in the archives on 21 January 1947], ERAF.1.5a.34, pp. 1–2.

40 A ferry line between Tallinn and Aegna was opened for the summer season in 1961. There were about 20 holiday resorts on that island in 1960–90. Aegna Island was within Tallinn’s administrative boundaries since 1975.

41 ESSR Council of Ministers Regulation no. 255-‐12, 1 June 1966, ERA.R-‐1.5.706, pp. 26–53.

42 See: Tõnu Tannberg. 1953. aasta amnestia: kas ainult varaste ja sulide vabastamine (The Amnesty of 1953: Was it the Release of Only Thieves and Crooks?). – Tuna, 2004, no. 3, pp. 37–51.

43 Лаврентий Берия. 1953. Документы. Moscow, 1999, pp. 45–48.

44 Käbin and Müürisepp to the USSR Minister of Internal Affairs, 21 September 1956, ERAF.1.5.405, pp. 42–43.

45 ESSR CPC Order no. 196-‐ks, 23 February 1957, ERA.R-‐1.5.431, 104; ESSR Council of Ministers Regulation no. 385-‐22c, ERA.R-‐1.5.429, pp. 119–127.

46 General term denoting the key positions and employees in the Soviet Union, see: http://www.estonica.org/en/Nomenklatura/.

47 For instance: Перечень должностных лиц. Приложение Но. 6 к приказу КГБ СССР, МВД СССР, МПС, Минморфлот, МГА, Минрыбхоз Но. 158/ДСП/225/43/ЦЭ/248/220/ДСП/548, 30 November 1983, ERAF, f. 17SM, n. 14, s. 109, not paginated. The four last institutions are the Ministries of Roads, the Naval Fleet, Civilian Aviation and the Fishing Industry.

48 It is not entirely clear exactly how “unlimited” entry ("въезжают свободно" in rules) was implemented in practice because KGB or other directives or instructions where these kinds of details could be described have not yet been found. Members of this group apparently did not have to show any documents and drove through checkpoints without stopping.

49 The only identification document that civilians had was the Soviet citizens’ passport, where until 1974 the bearer’s place of work was also entered. After 1974, an employment certificate was also required at checkpoints.

50 ERAF.131SM.1.375, pp. 102–104; J. Pihlau. Lehekülgi Eesti lähiajaloost. Merepõgenemised okupeeritud Eestist (Pages from Recent Estonian History. Escapes by Sea from Occupied Estonia), p. 74.

51 Report concerning agent and operative work of the State Security Committee 2nd Department under the Estonian SSR Council of Ministers in 1957. Report concerning agent and operative work of the State Security Committee 4th Department under the Estonian SSR Council of Ministers in 1957. Rahvusarhiiv, Tallinn, 2002, pp. 152–154.

52 Отчет об итогах работы наркомата внутренных дел Эстонской ССР за 1945-‐й год (Report concerning the work of the ESSR People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs in 1945), 8 March 1946. ERAF.17SM.4.40, p. 18.

53 The data presented is rounded off. Data for the first half of the year is indicated with an asterisk. ERAF.18SM.1.58, p. 66; 111, p. 22; 159, p. 20; 228, pp. 8, 13, 20; 267, pp. 3, 4, 22; 291, pp. 2–4; 312, p. 33; 341, pp. 48–49; 358, p. 187; 363,

p. 157; 391, p. 130; 405, pp. 175–176; 416, p. 167; 429, pp. 88, 213; 445, pp. 96, 186; ERAF.17SM.4.388, pp. 84, 163;

388, pp. 84, 163; 424, pp. 118, 341; 444, pp. 24, 284; 490, pp. 115, 288; 568, p. 369; 568, p. 369; 622, p. 30; 623, p. 147;

677, p. 292; 678, p. 165; 748, p. 128; 810, p. 255; 870, p. 244; 941, p. 159; 1020, pp. 75, 116; 1076, pp. 12, 121; 1126,

pp. 20, 127; 1321, pp. 211–212.

54 Доклад по паспортно-‐регистрационной работе (Report concerning work associated with passports and registration), 5 February 1954, ERAF.18SM.1.111, p. 52. For instance, according to the 1953 report, temporary permits issued for business trips and for personal reasons accounted for about 80% of all permits in equal proportions. The remainder was thus meant for permanent residents of the border belt. The proportion of permits issued to people who lived permanently in the border zone was about the same in 1984-‐1986 (for which precise data exists), in other words 16–21% of all permits.