Fighting in Two Uniforms: Anfilogi Fabrichnikov's Memoirs of the Second World War

Anfilogi Fabrichnikov (1907-1978) was from a family of Old Believers, an offshoot of the Russian Orthodox Church, who moved to Tallinn in the 1920s. After serving in the Estonian military, he held various jobs around Tallinn until his homeland was annexed by the Soviet Union in 1940 and, one year later, war broke out between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany.

The Second World War years were tumultuous for Fabrichnikov who, like many of his compatriots, found himself caught in the middle of a monumental battle between two totalitarian giants. Thanks to Fabrichnikov’s memoirs and a recent short documentary film, produced by the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory as part of the Kogu Me Lugu, oral history portal Fabrichnikov’s experiences are readily accessible as an example of a typical Estonian man from this era: Conscripted, sometimes more than once and into various uniforms, forced far away from his homeland and, ultimately, imprisoned in a Soviet Gulag camp.

Mobilisation

It was July 28, 1941. At such a time, the height of summer, Anfilogi Fabrichnikov might usually have been engaged in more pleasurable activities, but these were difficult times. One year earlier, the Soviet Union had illegally annexed his homeland of Estonia, and just recently had deported 10,000 of its citizens to remote labour camps and collective farms in Siberia and northern Russia. And now, the Soviet Union was under attack from Nazi Germany, and it was losing badly. In a matter of weeks, Estonia would be German-occupied territory.

In its frantic retreat, the Soviet forces sought to take with them whatever they could use and destroy what they could not, a policy that extended to human resources. Fabrichnikov and many of his compatriots found themselves mobilised into the ranks of the Red Army, ordered to gather 5 days’ worth of food and report for duty at Tallinn’s hippodrome.

After sleeping overnight under the stars, he marched to the train station the next day, as sobbing families and acquaintances watched their menfolk forced off to war. “They sat in groups”, he remembered, “sharing their thoughts and lamenting their fate”. Herded into overcrowded wagons, he and his comrades watched sadly as their loved ones, waving, shouting, and chasing after them, faded into the distance. Silence fell over his wagon.

Fabrichnikov remembered how some comrades, electing to take their chances on the run, jumped out of the moving train and disappeared into the forest. For those who remained, there was only sorrow as the train crossed the Narva River into Russia. They drank vodka, purchased during a brief stop along their journey, to lift their spirits, and soon the carriage was full of singing and laughing, although nobody knew where they were going.

Upon arriving in the town of Kotlas Arkhangelsk oblast, Fabrichnikov learned he was going north. He would spend the next several months in a Soviet labour column in remote regions of the Russian interior, engaged in slave labour under inhumane working and living conditions. Working from place to place and crossing hundreds of kilometres on foot in between, he and his comrades were pushed to their very limits, a test many would not survive.

Work projects included collective farms and building an airfield, the latter involving the infamously deadly task of logging. Work norms prescribed by their supervisors were impossible to fulfill, and those who could not fulfill them were forbidden from returning to the barracks for food and rest. The elements also took their toll, and the snow and darkness, mixed with the gruelling work regime, meant that Fabrichnikov’s troop was constantly tired, hungry, wet, and infested with lice.

“We all lost weight and weakened”, he wrote. His comrades “walked from work and fell into the snow… exhausted people cried like little children, asking each other for help to get up and make it to the rest area. But even their comrades had no strength”. The casualties mounted, and it would often happen that his troop would try to raise one of their own in the morning for work only to find he had died overnight.

The Soviet political officer attached to their troop, an “executioner with a savage heart” as Fabrichnikov recalled, allowed them no respite. They were sent to work and die every day, without breaks and in temperatures that reached below -30°C. “We could not understand who we were”, Fabrichnikov remembered. “Red Army soldiers or prisoners. But prisoners had a better life in some conditions”.

In the Red Army

This brutal state of existence lasted until February 1942 when, finally, the troop was given the opportunity to escape. The offer was simple, but potentially deadly: join the ranks of the Red Army in its epic struggle against the forces of Nazi Germany and its allies.

Eager to leave behind their brutal slave labour regime, Fabrichnikov’s group accepted. They embarked to Chebarkul near the border with Kazakhstan, a journey that finally provided them with adequate food and more humane treatment. Hiking through a blizzard, they arrived at the Voroshilov military camp, where they lived in large dugouts, each housing 400 people.

Their new Red Army uniforms and equipment did not protect Fabrichnikov and his comrades from the extremely cold temperatures and a dysentery outbreak. Fabrichnikov himself survived only thanks to the help of his friends, some of whom were medics. Many others perished, and were buried unceremoniously without clothes, coffins, or even a farewell ceremony. Strict military discipline was enforced, and training was conducted with wooden rifles.

In September 1942, the order was given to prepare for deployment. The camp was abandoned, and the long journey to the front, itself packed with further military training, began. Finally, on November 2, the troop arrived at Selizharovo, Kalinin oblast. There, they were ordered into a strict routine of nighttime marching and daytime resting. Yet more of his comrades began to collapse from exhaustion and starvation. There were, Fabrichnikov recalled, even cases of suicide “because people couldn’t bear the hardship and lacked strength”.

Thoughts of home and God, in particular an icon of St. Nicholas that he kept in his pocket, gave Fabrichnikov the strength he needed to continue. Ingenuity also helped; he and his unit devised a trick to avoid the exhausting nocturnal hike by lagging behind their formation and walking during the day instead of the night, catching up to the others before they departed at nighttime.

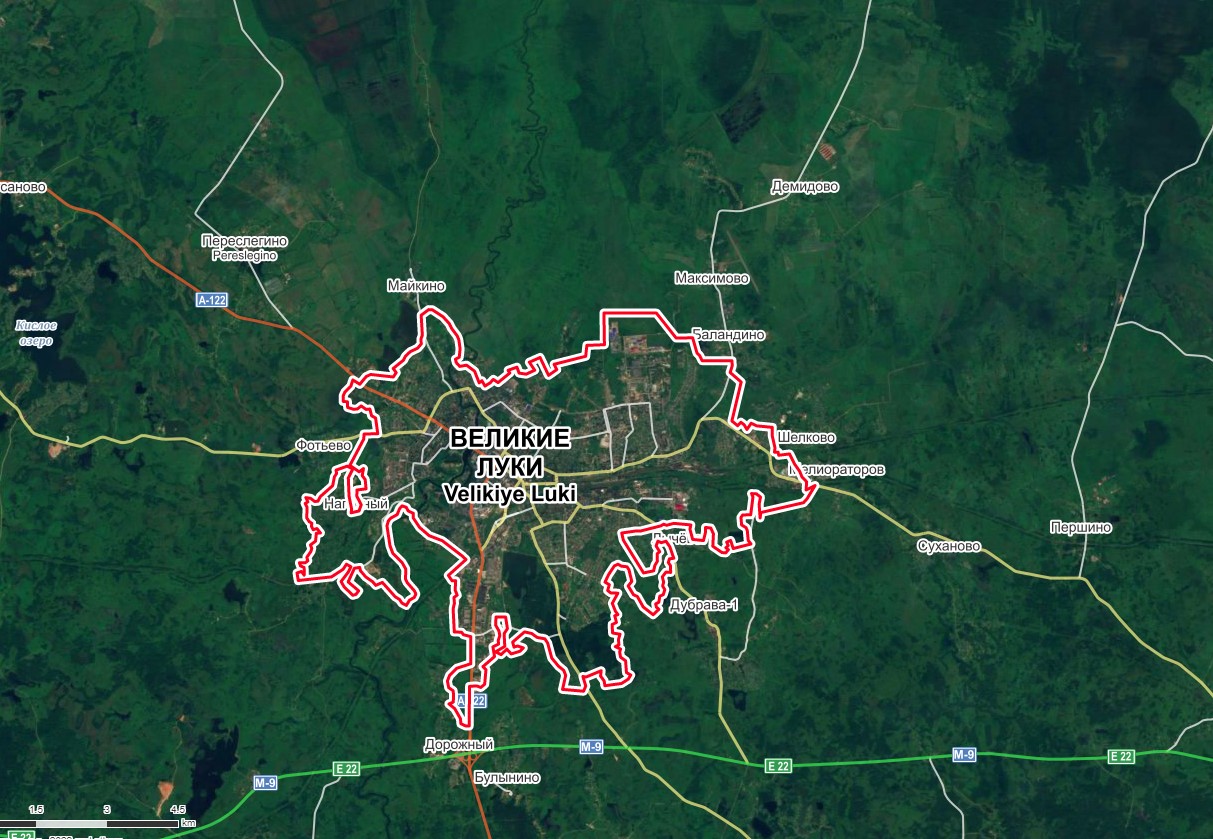

Their journey towards Velikiye Luki continued like this for a month and a half, covering a distance of 500 kilometres. They arrive on the frontlines, cold, wet, and exhausted. They were ordered to dig trenches, a difficult task on the frozen earth.

Soon, they were ordered to counterattack against the Germans who had recently taken a nearby village. Fabrichnikov remembered: “My heart sank with horror that our fate was being decided”. He said his prayers, and soon found himself in a trench just 100 meters away from the German lines, artillery shells whizzing over his head.

“Estonians, come over to our side!”

The call came, in fluent Estonian, from a man on the German side of the hill where the battle was being fought. Three minutes passed in silence before panic started to break out among Fabrichnikov’s comrades, some of whom began to cross the battlefield, hands raised in surrender. Fabrichnikov suggested to his lieutenant that they follow suit. The lieutenant silently agreed.

The Germans greeted them enthusiastically, slapping them on the back with cries of “Gut! Gut!”. German captivity treated Fabrichnikov’s troop much more kindly, and a hearty meal of bread, sausage, porridge, and potato rewarded them for their desertion. They were taken as prisoners away from the frontlines, sustaining casualties under intensive Soviet artillery fire.

After spending some months in a German prisoner of war camp in occupied Belarus, again characterised by far better living conditions than under the Soviets, the decision was reached to send them to a camp inside Estonia.

Fabrichnikov later wrote that “In the eyes of every comrade was great joy. After all, we were going to our native country, to our homeland!” Taking a train through Latvia, they were greeted on the border with Estonia by their countrymen, who had been waiting three days for their arrival with vast amounts of food. The air was alive with national songs, dancing, and merriment.

On February 18, 1943, the troop arrived at a German prisoner of war camp in Viljandi, a brass band playing the Estonian national anthem greeting them. Through March, Fabrichnikov reminisced, they sunbathed, watched movies and live music, listened to radio, and read newspapers. This was a time when, for once, he and his comrades were actually gaining weight rather than losing it. Of course, the Germans had every reason to offer them such favourable treatment; with the Soviets beginning to turn the tide of the war against them, the Germans were eager to score a propaganda victory within Estonia in the hopes of convincing the men to join the fight against the communist menace.

This blissful period did not last. Some weeks later, the rulers of German-occupied Estonia, Hjalmar Mäe and Generalkomissar Karl-Siegmund Litzmann, visited the camp. Appealing to the Estonians’ sense of patriotism, they implored them to join the ranks of the German army, an appeal that they agreed to. “Out of the frying pan and into the fire”, Fabrichnikov noted.

By April 6, 1943, he and his comrades were being released from the camp. Immediately, Fabrichnikov began to think about how he might avoid having to serve in the Germany army. Thus, on the day he was to present himself for service, he stayed home, feigning illness.

A military paramedic soon found him and ordered him to join his unit. Still desperate to avoid service, Fabrichnikov reported to the military infirmary. Unsure of how else to escape the frontlines, he complained of non-existent back pain. After being examined by a doctor, a translator came to see him, telling him:

“You are in luck! You’re excused from military service!”.

Fabrichnikov was elated. The documents he was provided with also exempted him from heavy labour, and so he found a job as a cart driver which, in his own words, he did not perform “properly”. Several weeks later he was summoned to a military commission, and again was deemed unfit for military service. He lived like this until 1944 when, finally, the Red Army returned to Estonia, and his family was evacuated to a village outside of Tallinn due to the Soviet bombing campaign.

Occupation and Arrest

After years of hardship and war, witnessed from both sides of the frontlines, Fabrichnikov sat and awaited his fate. It was September 22, 1944, when the Soviet tanks finally rolled into Tallinn as he and his father watched and drank. “It dampened my spirits”, he recalled, “but not too much because I was, after all, a bit tipsy”. Many of the Soviet troops were rowdy and drunk.

Almost one month later, on the morning of October 14, a knock came at the door. Awoken from his drunken sleep on the sofa, Fabrichnikov was greeted by a soldier in a grey overcoat, who invited him to “take a walk”. Fabrichnikov’s time had come. “I knew then that I would never be going back. That was my last hour of freedom”.

He said a final, tearful farewell to his mother, a scene he did not forget for the rest of his life. His interrogation lasted for one month. Interrogated at night and under harsh conditions, he confessed to whatever ‘crimes’ his captors accused him of and pleaded for clemency for his family. His family were now guilty by association with an ‘enemy of the people’, and he and his wife divorced.

Fabrichnikov and other victims found guilty under article 58.1 (b) (which punished those found guilty of treason against the ‘motherland’, regardless of cases like Fabrichnikov whose true ‘motherland’ was Estonia) of the Soviet penal code were loaded into boxcars under heavy guard for a three-day journey to their prison camp. Fabrichnikov remembered the pain of once again being torn from his homeland: “At night, we set off and I bade farewell to my homeland. I knew they were taking us from Estonia. The train sped on”.

After being treated like cattle on this freezing journey, he was subjected to further humiliation upon his arrival at the camp when his silver cross and chain were seized by the guards. “We have no Orthodox people here”, they told him proudly. The prison thieves took what remained of his personal belongings under threat of violence. Living conditions, and especially the daily food allowance, were appalling, a lifestyle Fabrichnikov was only too accustomed to by now.

He was released from the labour camp only in August 1954, almost a year and a half after Stalin’s death. He returned, as is daughter later noted, with his health “ruined”, and his personality “changed”.

Jesse Seeberg-Gordon is an Australian historian whose primary interest is the Soviet Union and its successor states. He graduated from the University of Melbourne in 2020, where his honours thesis, which dealt with an Australian-Soviet diplomatic incident in the 1970s, won the Brian Fitzpatrick Prize for Best Honours Thesis in Australian History. He currently works with the Estonian Institute of Historical Memory.